Author and California Pioneer

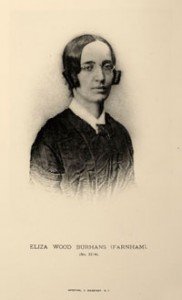

Eliza Farnham (1815-1864) was an author, feminist, lecturer, activist for prison reform, and early proponent of the superiority of women. In her day, Farnham was once one of the most highly praised women nonfiction authors in the United States. She made national headlines with her writings and was at the vanguard of several social and political movements of her time, including abolitionism, women’s rights and Spiritualism. Farnham’s reform work was also her career and a matter of financial necessity throughout her life.

Eliza Farnham (1815-1864) was an author, feminist, lecturer, activist for prison reform, and early proponent of the superiority of women. In her day, Farnham was once one of the most highly praised women nonfiction authors in the United States. She made national headlines with her writings and was at the vanguard of several social and political movements of her time, including abolitionism, women’s rights and Spiritualism. Farnham’s reform work was also her career and a matter of financial necessity throughout her life.

Early Years

Eliza Burhans was born on November 17, 1815 in the Hudson Valley town of Rensselaerville, New York, the daughter of Cornelius and Mary Wood Burhans. Eliza’s mother died in 1820, after which five-year-old Eliza was separated from her father and siblings and exiled to a rural community in western New York State. There she was placed in the home of the Warrens, a childless couple.

Her book My Early Days (1859) is a record of her childhood, a portrait of relentless suffering among ignorant, brutal people. Eliza worked as a servant for the Warrens, who were Quakers, yet thoroughly atheistic. The only reading materials in their house were condemnations of religion and praise of reason, including Paine and Voltaire.

The personal struggle described throughout the book reaches far beyond issues of gender. At the beginning of the book, Eliza is not even called by her real name but by hostile nicknames. One of these is Tonewanta, a reference to her dark, Indian-like complexion, deepened by exposure to the sun and hard outdoor work. Largely self-educated, Eliza found solace in books and nature.

Finally, after seven years under these conditions, she contacted a brother who came to bring her out of the wilderness. “This is my niece,” he lied when they returned together to the Hudson River Valley of her birth, “a wild girl, whom I have just caught in the forests of the West.” This is where My Early Days ends.

At age 15 Eliza went to live with an aunt and uncle and briefly attended the Albany Female Academy. The aunt, she later recalled, raised her through “neglect and hardship.” As part of a continuing effort to free herself, young Eliza stole money from her aunt, convinced that it was owed her as compensation for her labor and the unfulfilled obligation to educate her.

Marriage and Family

In 1835 Eliza Burhans moved with her brother to Tazewell County, Illinois, where they joined a married sister, Mary Roberts. In 1836, Eliza married lawyer and author, Thomas Jefferson Farnham, ten years her senior. For the next five years the couple lived on the Illinois prairie. The couple had three sons: Charles (1837-1838), Charles Haight (1841-1929) and Edward (184?-1855).

In 1839 Thomas Farnham organized and took command of a an ill-fated invasion to drive out the British in the Willamette Valley of Oregon. He then turned to central California as a more promising site for his expansionist ambitions. In Santa Cruz, he joined the growing Yankee community and acquired land from a local Californio family in payment for legal services.

Thomas Farnham was the author of several travel books: Travels in Oregon Territory (1842); Travels in the Great Western Prairies (1843); Travels in California, and Scenes in the Pacific (1845); A Memoir of the Northwest Boundary-Line (1845); and Mexico, its Geography, People, and Institutions (1846).

Career in Social Reform

Meanwhile, Eliza Farnham had moved from Illinois to New York in 1841, and was struggling to support herself and her children. She became involved in the reform movements that were prevalent in the 19th century, and soon became known in the social reform circles of New York.

Still looking for paying work, Eliza Farnham took a job as Women’s Warden of the infamous Sing Sing prison in Ossining, New York in 1844. Her appointment, which she won through her connection with Horace Greeley and other reformers, brought her a burst of favorable attention and subsequently considerable notoriety.

Following in the footsteps of the British Quaker Elizabeth Fry, Farnham adapted modern notions of rehabilitation to women prisoners, formerly regarded as morally irredeemable. She instituted reforms, emphasizing kind treatment of prisoners, the use of music, and other improvements in the living environment at Sing Sing. As her assistant, Farnham hired Georgiana Bruce, a young English immigrant and former member of the utopian community at Brook Farm.

Farnham’s particular interest was in using phrenology, one of the most popular of the new psychological sciences, as a means to diagnose and treat female prisoners. The distinguishing feature of phrenology is that a person’s character could be read by examining and measuring the skull of the individual. Farnham was a pivotal figure in the argument for phrenology’s efficacy in treating prisoners in the mid-1840s.

Literary Career

Following her husband’s example, in 1846 Eliza Farnham published her first book about her years in Illinois, Life in Prairie Land, one of the earliest female-authored accounts of the life of American settlers on the frontier. It became an enormously popular travel and nature book.

While Farnham came to believe that exceptional women like herself could have a leading role in the unfolding of the national destiny in the West, she also believed that the majority

“of my sex… unfortunate as to have had their minds thoroughly distorted from all true and natural modes of action by an artificial and pernicious course of education,”

and therefore could not enjoy the “emancipation which so endears the Western country to those who have resided in it.”

What remained from her experience was a contempt for the moral weakness and frivolity of eastern middle-class women. Hinting at her later belief in women’s superiority over men, she reported that western women could not be lazy even if they wanted to be, given the number of male visitors dependent on their domestic skills; the men, however, “may be pronounced unequivocally indolent.”

Despite the improvements Farnham made at the women’s prison at Sing Sing, her liberal views brought her into conflict with other staff members. The prison’s trustees came to regard her as a dangerous radical, and in 1848 they succeeded in driving her out.

Farnham left New York for Boston, where she worked for several months for physician and reformer Samuel Gridley Howe at the New England Asylum for the Blind (now the Perkins Institute). Farnham worked most notably with deaf and blind student, Laura Bridgman. And she even read draft versions of Life in Prairie Land to Bridgman using a finger spelling method devised by Howe and Laura’s teachers.

During this period, Farnham also wrote for magazines. In Brother Jonathan she debated the editor, John Neal, on women’s rights, and humorously described an Illinois camp meeting in the Knickerbocker. In The Prisoner’s Friend she revealed how Laura Bridgman, her student at the New England Asylum for the Blind, learned to communicate in a trail-blazing technique used years afterward with Helen Keller.

In late 1848 she was teaching in Boston when she learned that her husband Thomas Farnham – who had been practicing law and running a freight business in California – had died suddenly in San Francisco on September 13, 1848, leaving her some real estate. This came at a time when the discovery of gold in California was drawing hordes of would-be prospectors aboard every ship.

Eliza Farnham made plans to head west to settle her husband’s estate. To fund the trip, she went to work on a plan to bring a boatload of good women to civilize California. Her project, which gained the endorsement of several well-known reformers, was nevertheless unsuccessful.

She and her two sons finally sailed for California in May 1849 with another woman, Miss Sampson, and a young nursemaid. Along the way, the nursemaid ran off with a crew member. When the ship stopped in Valparaiso, Farnham went in search of a replacement. The captain departed without her, taking the rest of her goods, including her children.

In California

Farnham waited in Chile almost two months for the next ship and arrived in San Francisco in February 1850 to find one of her sons quite ill. With her children and her baggage, Farnham finally made her way to Santa Cruz, where she took possession of the 200-acre ranch that Thomas Farnham had left her, naming the place El Rancho La Libertad.

She focused her initial housekeeping efforts on simply getting a stove installed. During the three-day period that she called the ‘siege of the stove,’ a hired man failed at the task, as did her friend Miss Sampson. Then Farnham tackled it: “On the third day, it was agreed that stoves could not have been used in the time of Job, or all his other afflictions would have been unnecessary.”

Eliza Farnham quickly recognized that women in California would have to work. She described the ‘casa’ at her Santa Cruz ranch as: “Not a cheerful specimen, even of California habitations – being made of slabs, were originally placed upright, but which have departed sadly from the perpendicular in every direction…”

Not afraid of labor, Farnham set herself the task of building a house:

My first participation in the labor of its erection was the tenanting of the joists and studding for the lower story, a work in which I succeeded so well, that during its progress I laughed, when I paused for a few moments to rest, at the idea of promising to pay a man $14 or $16 per day for doing what I found my own hands so dexterous in.

However, the realities of everyday life in gold-rush California were daunting, but when Farnham’s friend and assistant at Sing Sing Georgiana Bruce (later Kirby) joined her and her sons the following year, Farnham was again hopeful:

She fills up a great place in my dark world and comes to me like a pleasant breeze or a bright sun after one of our long rains. We are going to be very independent and free… dashing about at our discretion.”

The women roofed and joined the new house, broke sod and set out potatoes, planted fruit trees and raised poultry. To be able to work and move freely, they wore bloomer costumes, to their neighbors’ amusement, discussing the future of women as they hammered and planted and harvested.

In California, Eliza Farnham farmed the land, taught elementary school, worked on her writing and became a leading abolitionist, author and feminist – all of which helped support herself and her children. In the mid-1850s she embarked on a series of well-attended lectures throughout Northern California, promoting her views on Spiritualism, women’s health issues and other social concerns of the time.

She also closely observed local society, which, as she saw it, was in desperate need of women’s moral influence. California, In-doors and Out, Or, How We Farm, Mine, and Live Generally in the Golden State (1856) was the first book about California written by a woman. In this work, Farnham called upon women to bring their highest influence to bear on the evils engendered in an all-male, lawless society – California’s population was over 90 percent male at that time.

In California In-Doors and Out Farnham also included a series of conversations between herself and Georgiana Bruce, in which Bruce subscribed to the ideas about equality of the sexes being put forward in the East by the women’s rights movement. However, Farnham believed that women neither needed nor would benefit from individual legal and political rights, because women were already superior to men.

On March 23, 1852, Eliza Farnham had married William Fitzpatrick. Although she preached marriage as the highest service a woman could render to the new state of California, her own was brief and abusive. They had a daughter who died in infancy, and Farnham’s youngest son Eddie died in 1855. In 1856, she obtained one of the first recorded divorces in American California and left the state.

Back in New York in 1856 she devoted herself to the study of medicine, wrote and lectured. During the financial panic of 1857, Farnham founded the Women’s Protective Emigration Society, escorted several hundred unemployed women to jobs in Illinois and Indiana, and inspired more public praise:

Few ladies… have labored with more true zeal… to ameliorate the condition of the laboring class of women, and those who, by reason of misfortune, need aid, than Mrs. Eliza W. Farnham. Truly can she be classed among our noblest female philanthropists…. God speed her in her noble mission.

While she was in the midst of writing Woman and Her Era, Farnham presented her theory of Female Superiority to the 1858 Women’s Rights Convention in New York City. She agreed with most other women’s rights advocates that much about the current condition of women constituted a kind of enslavement: the unjustness of male domination and female subordination in marriage laws, and the sexual double standard that made women guilty of sexual crimes while ignoring and forgiving men.

She also spoke about the exploitation and underpayment of women workers, calling for unfettered freedom for individual women to seek employment and opportunity. But it was her view that women were superior to men that was hotly debated. Other feminists disliked the insult this idea conveyed to men, especially men who supported women’s rights.

Farnham was not well received by the women’s rights audience. Her class elitism and resentment for existing women – as opposed to the ideal essence of Woman – made the doctrine of the Superiority of Woman an unlikely candidate for a popular political ideology. Polish Jew and feminist, Ernestine Rose, who shared the platform with Farnham, regarded her as an opportunist who “wished to avail herself of whatever had been done, not caring to identify herself with the movement.”

Late Years

Eliza Farnham returned to California to serve as matron of the state’s first mental hospital, the Stockton Insane Asylum, from 1859 through 1862. When she again began her lecture tours there, newspapers covered her every appearance, including her address to the California State Legislature on the inadequacies of their new state prison at San Quentin.

During the Civil War, she worked with the Women’s Loyal National League and joined with abolitionists who sought to convince Abraham Lincoln to end slavery. Farnham went to the Gettysburg battlefield in July 1863, arriving a few days after the fighting had stopped, ready to help nurse the thousands of wounded and dying men who still awaited care. Exhausted and overworked, she perhaps contracted an infection there.

After a second trip to California in 1864, Farnham returned East and worked for the next five months to complete her third book, the two-volume Woman and Her Era (1864). Here, she openly rejects both the call for equal rights and the claim that the two sexes are fundamentally the same. Although she appreciates the efforts of women’s rights advocates, she regards their movement as “erroneous in philosophy… and partially mistaken in direction.”

In Woman and Her Era, she listed many female reformers and philanthropists as representatives of true womanly character. The list included Lucy Stone, Lucretia Mott and Lydia Maria Child, but omitted more radical women’s rights advocates such as Ernestine Rose and Susan B. Anthony.

Farnham’s life ended before she could witness either the schisms in or many of the successes of the women’s movement. She became ill with consumption (tuberculosis) in late 1864.

Eliza Farnham died on December 15, 1864 in New York City at age 49. She was buried at Milton-on-Hudson, New York. Her only son to reach maturity, Charles Haight Farnham, became a writer.

A year and a half later, at the first women’s rights convention after the Civil War, writer Caroline Healey Dall mentioned Farnham’s life, work and death. Her tribute was restrained, even hostile. Farnham’s life, claimed Dall, had been “a bitter disappointment to herself,” a charge to which Elizabeth Cady Stanton responded with far greater empathy. Stanton was exactly the same age as Farnham, shared many similar ambitions, and seemed to understand that their paths had been, at least for a time, similar.

British historian E. P. Thompson, in his classic study of the precursors of British working-class consciousness, argued for the importance of studying byways of the past, which only in retrospect do we know to be historic dead-ends, but which at the time seemed as straight a road into the future as any other.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Eliza Farnham

Ellen Carol DuBois @ Common-Place: Seneca Falls in Santa Cruz

Two Women Reformers in Gold Rush California

American National Biography: Eliza Wood Burhans Farnham