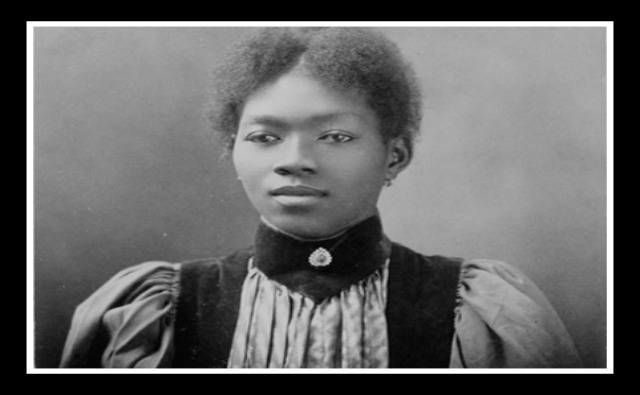

First African American Woman Novelist

Image: Harriet Wilson Memorial Statue

Bicentennial Park, Milford, New Hampshire

Harriet Wilson is considered the first African American of any gender to publish a novel on the North American continent as well as the author of the first novel by an African American woman. Her novel Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black was published anonymously in 1859 in Boston, Massachusetts, and was not widely known. It was re-discovered in 1982 by Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., which led to the publication of a facsimile edition in 1983.

Image: Harriet Wilson Memorial Statue

Bicentennial Park, Milford, New Hampshire

Early Years

Born a mixed race free person of color in Milford, New Hampshire on March 15, 1825, Harriet Adams was the daughter of Margaret Ann (or Adams) Smith, a washerwoman of Irish ancestry, and Joshua Green, an African American “hooper of barrels.” After Green died when the girl was young, her mother abandoned Harriet at the farm of Nehemiah Hayward Jr., a wealthy Milford farmer.

As an orphan, Harriet was bound by the courts as an indentured servant to the Hayward family, a customary way for society to arrange support for orphans at that time. The intention was that, in exchange for labor, the orphan child would receive room, board and training in life skills, so that she could later make her way in society.

Researchers have been able to document that the Haywards were the family referenced in Our Nig as the Bellmonts, and that they physically and mentally abused Harriet from the age of six to eighteen. The family called her Nig.

After her indentured servitude ended, Harriet worked as a house servant and a seamstress in households in southern New Hampshire and central and western Massachusetts.

Marriage and Family

Harriet married Thomas Wilson in Milford on October 6, 1851. Wilson had been traveling around New England giving lectures based on his life as an escaped slave. Although he continued to periodically lecture in churches and town squares, he told Hattie that he had never been a slave and that he used his story to gain support from abolitionists.

Wilson abandoned Harriet soon after they married. Pregnant and ill, she was sent to the Hillsborough County, New Hampshire Poor Farm in Goffstown, where her only son, George Mason Wilson, was born. His probable birth date was June 15, 1852. Soon after George’s birth, Wilson reappeared and took the two away from the Poor Farm. Wilson returned to sea, where he served as a sailor, and died soon after.

Now a widow, Harriet Wilson could not make enough money to support herself and her son and provide for his care while she worked. She returned her son George to the care of the Poor Farm, where he died at the age of seven on February 16, 1860.

Our Nig

Seeking a means to earn a living, Wilson moved to Boston, where she wrote a novel she titled Our Nig. On August 18, 1859, she copyrighted the novel, and a copy of it was deposited in the Office of the Clerk of the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts. On September 5, 1859, the novel was published anonymously by George C. Rand and Avery, a Boston publishing firm.

The first novel published by an African American woman, Our Nig recounts the life of Frado (short for Alfrado), a biracial girl left by her parents to be raised by a prominent Milford, New Hampshire family in the 1830s and 1840s. Frado endures a childhood of deprivation and isolation as an African American child – not quite a slave but certainly not free – in an antebellum New England town.

The abuse Frado suffered at the hands of her mistress illustrate Wilson’s then-controversial claim that blacks might be as mistreated in the free North as they were in the slaveholding South. In this compelling tale, Wilson chronicles the racial prejudice that permeated a community despite the presence of famous abolitionists and their activities in and around Milford.

It has been suggested that that Our Nig did not receive critical acclaim when it was first published because it did not conform to the contemporary genre of the slave narrative, the main form of African American literature in the 19th century. Slave narratives were written by a number of former slaves, including Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass, and told of their enslavement and their ultimate escape to freedom and a better life. These tales were publicized by abolitionists to illustrate the evils of slavery.

Our Nig‘s central theme is the injustice of the indentured servitude system and the white racism experienced by a free black in the northern United States before the Civil War. It has been suggested that abolitionists may have consciously decided not to promote Our Nig because the novel recounts incidents of bigotry by whites toward a free African American in the free states. No redeeming quality here.

In 1863, Harriet Wilson’s name appeared on the “Report of the Overseers of the Poor” for the town of Milford. In 1867, she was listed in the Boston Spiritualist newspaper Banner of Light as living in East Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she had become involved with the Spiritualist church.

Spiritualism is a belief system or religion which claims that spirits of the dead residing in the spirit world have both the ability and the inclination to communicate with the living. Anyone may receive spirit messages, but formal communication sessions (seances) are held by mediums, who can then provide information about the afterlife. Spiritualism reached its peak growth from the 1840s to the 1920s.

Harriet Wilson became active in the local Spiritualist community, and to earn a living she gave lectures, either while entranced or speaking normally, for which she was paid. She spoke at camp meetings, in theaters and in private homes throughout New England, and shared the podium with well known speakers such as Victoria Woodhull and Andrew Jackson Davis.

Wilson subsequently moved across the Charles River to the city of Boston, where she became known in Spiritualist circles as the colored medium. From 1867 to 1897, she was listed in the Banner of Light as a trance reader and lecturer. In 1870 she traveled to Chicago as a delegate to the American Association of Spiritualists convention.

Wilson also delivered lectures on labor reform and children’s education. Although the texts of her talks have not survived, newspaper reports imply that she often spoke about her life experiences, sometimes providing humorous commentary. When she was not pursuing Spiritualist activities, Wilson was also employed as a nurse and clairvoyant physician (healer).

Late Years

On September 29, 1870, Wilson married John Gallatin Robinson, an apothecary of English and German descent who was nearly 18 years younger than she. From 1870-1877, they resided at 46 Carver Street, after which it appears that they separated. After that date, city directories list Wilson and Robinson in separate lodgings in Boston’s South End. No record has been found of a divorce, but divorces were infrequent at the time.

Wilson continued to be active in the Spiritualist community. During the 1870s she was involved in the organization and maintenance of Children’s Progressive Lyceums, the Spiritualist church equivalent of Sunday Schools; she organized Christmas celebrations; she participated in skits and playlets; and sometimes sang as part of a quartet. She was also known for her floral centerpieces and candies she made for the children.

Despite Wilson’s long and eventful life after Our Nig, there is no evidence that she ever wrote anything else for publication. For nearly 20 years (1879-1897), she was the housekeeper of a boardinghouse in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street in the South End of Boston. She rented out rooms, collected rents and provided basic maintenance.

On June 28, 1900, Harriet Wilson died at age 75 in the Quincy Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts and was buried in that town’s Mount Wollaston Cemetery.

In 1982, Our Nig was rediscovered by professor and scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. and gained national attention when he confirmed that it was the first novel by an African American to be published in the United States. Until then, the novel and its author had been forgotten. Only 42 copies of the original edition are known to exist.

In 2006 professors William L. Andrews and Mitch Kachun stated that Julia C. Colllins’ The Curse of Caste; or The Slave Bride (1865) should be considered the first “truly imagined” novel by an African American to be published in the U.S. They argued that Our Nig was more autobiography than fiction.

Gates responded that numerous other novels and other works of fiction of the period were in some part based on real-life events and were in that sense autobiographical, but they were still considered novels. Examples include Ruth Hall by Fanny Fern, Little Women by Louisa May Alcott and The Coquette by Hannah Foster.

The first known novel by an African American was Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter (1853) by William Wells Brown. However, it was first published in the United Kingdom, where he was living at the time.

In her article “Dwelling in the House of Oppression: The Spatial, Racial, and Textual Dynamics of Harriet Wilson’s Our Nig,” Lois Leveen argues that, although the novel is about a free black in the north, the “free black” is still oppressed.

Excerpt from Our Nig, shortly after Frado’s indentured servitude began:

Frado was called early in the morning by her new mistress. Her first work was to feed the hens. She was shown how it was always to be done, and in no other way; any departure from this rule to be punished by a whipping. She was then accompanied by Jack to drive the cows to pasture, so she might learn the way. Upon her return she was allowed to eat her breakfast, consisting of a bowl of skimmed milk, with brown bread crusts, which she was told to eat, standing, by the kitchen table, and must not be over ten minutes about it. Meanwhile the family were taking their morning meal in the dining-room.

SOURCES

The Harriet Wilson Project

Wikipedia: Harriet E. Wilson