Poet and Novelist in the Civil War Era

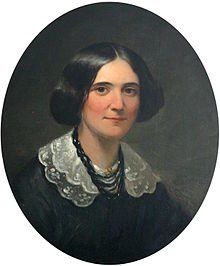

Alice Cary (1820-1871) was a poet and author, and the sister of poet Phoebe Cary (1824–1871), who would become Alice’s lifelong companion. Alice Cary’s strong desire to be independent and to forge her own literary career prompted her to move alone to New York City at age 30. Cary was a most unusual 19th century woman who earned her own money, owned her own home and ran her own life – a true pioneer on many levels. A prolific writer, she ruined her health by the constant need to express herself.

Alice Cary (1820-1871) was a poet and author, and the sister of poet Phoebe Cary (1824–1871), who would become Alice’s lifelong companion. Alice Cary’s strong desire to be independent and to forge her own literary career prompted her to move alone to New York City at age 30. Cary was a most unusual 19th century woman who earned her own money, owned her own home and ran her own life – a true pioneer on many levels. A prolific writer, she ruined her health by the constant need to express herself.

Alice Cary was born on April 26, 1820 on a farm in Hamilton County, Ohio, eight miles north of Cincinnati. This was then considered the western frontier of the United States. After returning home from the War of 1812, Robert Cary had purchased from his uncle 27 acres of land, which he called Clovernook Farm. In 1814 he built a three-room frame house for his family, which was the birthplace of Alice and Phoebe Cary.

The Cary family earned their living through farming. Robert and Elizabeth Cary were converts to Universalism. Pious and Bible-oriented, they were theologically liberal and passed to their children a strong sense of equality and social justice. From their shy, tender father who often recited poetry, hymns and scriptural passages while doing farm work.

According to Alice, Elizabeth Cary was “a woman of superior intellect and of a good, well-ordered life. In my memory she stands apart from all others, wiser and purer, doing more and loving better than any other woman.” Though burdened with household duties, Elizabeth found time to pursue interests in history, biography and politics. From her Alice inherited a common sense attitude, and she encouraged Alice to practice her writing.

The nearest village was called Mount Healthy and its surrounding farms and houses became the Clovernook memorialized in Alice Cary’s short fiction. The farm was a good distance from any school, and the father could not afford to give his large family of nine children a good education. In a letter Alice described her formal education as “limited to the meagre and infrequent advantages of an obscure district school.” But Alice and her sister Phoebe were fond of reading and studied constantly.

The two-story white brick house now known as Cary Cottage was built in 1832. Late in life, Alice Cary told a friend: “In the autumn of 1832, by persevering industry and frugal living, the farm was at last paid for, and a new and more commodius dwelling erected for the reception of the family. This new dwelling, which is still standing, is no more than the plainest of farm-houses, yet it represents a degree of comfort only attained after a long struggle.”

While she was growing up, Alice Cary idolized her older sister Rhoda, according to Alice, the most gifted member of the family. On the way to and from school Rhoda would tell stories, and “when we saw the house in sight, we would often sit down under a tree, that she might have more time to finish the story.” Alice never fully recovered from the death in 1833 of this sister who not only taught her the art and fascination of storytelling but also encouraged her first attempts at poetry.

As Universalists, the Carys subscribed to the The Trumpet and Universalist Magazine, a Boston periodical whose Poet’s Corner, according to sister Phoebe, served as Alice’s major model and source of inspiration. Their parents encouraged the sisters’ writing talents.

Two years after their mother died in 1835, Robert Cary married a harsh, childless widow who thought writing was a sinful waste of time. While the sisters willingly helped with household work, they were determined to study and write after the day’s work was done. Sometimes the girls were refused the use of candles, and resorted to a saucer of lard with a bit of rag for a wick as their only light after the rest of the family had retired, and wrote secretly into the night.

Literary Career

Evidently, Alice Cary began writing verse at an early age. In 1838, when Alice was 18, Cincinnati’s Universalist paper, The Sentinel, printed her first major poem “The Child of Sorrow.” The poem was praised by influential critics including Edgar Allan Poe and Horace Greeley.

Alice Cary was the more prolific, writing diligently, compulsively, every day. For ten years she published poems and short stories without pay, wherever she could, mostly in Universalist and Cincinnati publications. In 1847 she received her first payment of $10 from the Cincinnati Sentinel. The Sentinel accepted her work for many years afterwards.

In 1847, however, Cary began to write fiction for the National Era in Washington, DC. The Era was an abolitionist paper best known for serializing Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Its editor, Gamaliel Bailey, had recently moved from Cincinnati to DC. The Era brought Cary a national audience; it also brought her the attention of John Greenleaf Whittier, notable for his support of 19th century American women writers.

In 1848, Rufus Griswold, editor of two anthologies of American poetry and prose, wrote to Alice and Phoebe Cary requesting material for inclusion in his latest project, The Female Poets of America. Edgar Allan Poe wrote a review of this anthology for the Southern Literary Messenger (February 1849) and singled out Alice Cary’s “Pictures of Memory” to be “decidedly the noblest poem in the collection.”

Through Rufus Griswold’s recommendation, a Philadelphia publisher accepted a collection of the sisters’ poetry, which was issued as Poems of Alice and Phoebe Cary (1850). Some two-thirds of the poetry was written by Alice. By the spring of 1850, Alice and Griswold were corresponding through letters which were often flirtatious, but it ended by the summer of that year.

Poems made the Cary sisters well-known, and earned them $100. In 1850 they took a three-month trip to the East – mainly New York City and Boston – and met some of the people who had given them praise and encouragement. Alice Cary in particular was well on her way to becoming a writer with a national reputation.

In November 1850 Alice Cary moved to New York City, determined to make a living as a writer – a daring step for a shy, gentle woman. Phoebe soon joined her there. Poetry by itself has never been a lucrative way to make a living for most writers. Nevertheless the Cary sisters persisted, earning whatever they could and living frugally within their meager income.

Alice’s poems appeared regularly in leading magazines such as Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly, New York Ledger, New York Weekly, and Packard’s Monthly, while Phoebe had success in Scribner’s Monthly, Galaxy, and Putnam’s Monthly. Together they developed a circle of admiring, supportive friends.

In 1852 Alice Cary published Clovernook: or, Recollections of Our Neighborhood in the West. These fictional sketches lovingly portrayed the country life of her childhood, but also dealt realistically with the hardship, economic deprivation and death so common to that experience. She followed this success with more Clovernook sketches the next year, Clovernook Children (1854) and Pictures of Country Life (1859). The books sold well in England as well as America.

Modern day critic Judith Fetterley characterizes Alice, as a writer of fiction, as “a master of the uncanny, of the dream sequence, of narrative generated by the logic of deeply interior and nonrational psychic life,” in the tradition of Edgar Allen Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

In 1855 Alice Cary bought a modest house on 20th Street which became a popular salon for actors, writers, clergy, feminists, social reformers and philanthropists; in short, all the noted contemporary names. For over 15 years the Cary sisters hosted tea and conversation at their Sunday evening receptions.

Among the more distinguished of the frequenters of the Cary home were New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, poet Bayard Taylor, poets Richard and Elizabeth Stoddard, poet John Greenleaf Whittier, Hans Brinker author Mary Mapes Dodge, Anna Dickinson, early journalist Jane Cunningham Croly, social reformer George Ripley, Harper’s Bazaar editor Mary Booth, socialite Madame Le Vert and feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

The Carys had a passion for justice and hated oppression of any kind, especially the wrongs done to women in their day. Although Alice was in sympathy with the goals of the suffrage movement, she never actively joined, preferring to do her part through writing. Her novels and stories sometimes depicted the plight of poor, single, pregnant, abandoned women. Others portrayed self-confident, happily married women who remained true to themselves instead of conforming to societal expectations.

At the urging of editor and feminist Jane Croly, Alice reluctantly agreed to become the first president of the New York Woman’s Club, later named Sorosis, which was created to help women think for themselves, gain new means of employment and overcome barriers that denied them opportunities. Phoebe served as an assistant editor for Susan B. Anthony‘s newspaper The Revolution.

Alice Cary wrote for the Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, Putnam’s Magazine, the New York Ledger, the Independent and other literary periodicals. Her articles, whether prose or poetry, were also gathered into volumes which were received well in the United States and abroad. Cary also wrote novels and poems which did not make their first appearance in periodicals.

The constant need to publish in order to support herself took its toll on Cary’s literary reputation. Though loved by the public, her poems and stories appeared too often for critics to take them as seriously as they might have otherwise. But writing daily was a psychological as well as financial need for Cary. Her work was the center of her existence and her means of expressing who she was and what she believed.

Cary was an indefatigable worker, and her short story collection Clovernook, or Recollections of Our Neighborhood in the West (1852) was tremendously popular. Her other published fiction includes Clovernook Papers (1851); Hagar, a Story of To-day (1852); Married, Not Mated (1856); The Bishop’s Son (1867); The Lover’s Diary (1867); and Snow Berries, a Book for Young Folks (1869). Alice’s poetry appeared as Lyra and Other Poems (1853), Maiden of Tlascala (1855) and Ballads, Lyrics and Hymns (1866).

Late Years

It is obvious that Cary’s literary output slowed considerably during the late 1850s and early 1860s. Though the events of her life tell a story of achievement against the odds of being poor, female, uneducated and unsupported, Cary evidently paid a high price for her success. Her biographer presents her as working to live and living to work, finding pleasure only in labor and permanently destroying her health by refusing to rest.

Later in life, Cary became increasingly crippled. During her last two years she was finally bedridden and lived in great pain. She continued to write when her health permitted and was cared for faithfully and lovingly by her stronger sister Phoebe.

Alice Cary died of tuberculosis on February 12, 1871 at her home in New York at age 50. She was buried two days later in Brooklyn’s Greenwood cemetery. The pallbearers at her funeral included P. T. Barnum and Horace Greeley. Cary left an unfinished novel, The Born Thrall, and enough uncollected poems to fill two more volumes.

Almost every newspaper across the United States carried an obituary that praised Alice Cary’s contributions to literature. Those who regularly read her poetry felt they had lost a personal friend. Phoebe Cary wrote a beautiful and touching tribute to her sister’s memory, which was published in the Ladies’ Repository.

Phoebe Cary health had begun to deteriorate during Alice’s last year. Battling fatigue and fever, probably caused by malaria, she attended to her sister’s needs and ignored her own. When Alice died, the light went out of Phoebe’s life. Exhausted, grieving and in poor health, she became severely depressed. She sat in a darkened room unable to eat or work, rejecting all visitors.

Concerned friends arranged for Phoebe to visit Newport, Rhode Island, in hopes that a different environment would revive her spirits. The result was contrary to expectations. She soon was bedridden with fever and chills. Phoebe Cary died on July 31, 1871, only six months after Alice’s death. She was laid to rest next to her beloved sister.

SOURCES

The Cary Sisters

Wikipedia: Alice Cary

Heath Anthology of American Literature: Alice Cary