One of the First Women Lawyers in the United States

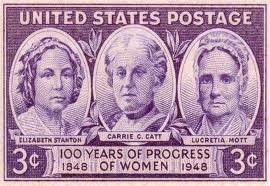

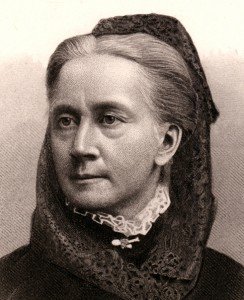

Belva Lockwood (1830–1917) was the first woman admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court when she pursuaded Congress to open the federal courts to women lawyers in 1879, and the first woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court. She was also active in working for women’s rights and overcame many social and personal obstacles related to gender restrictions. Lockwood ran for president in 1884 and 1888 on the ticket of the National Equal Rights Party and was the first woman to appear on official ballots.

Belva Lockwood (1830–1917) was the first woman admitted to the bar of the U.S. Supreme Court when she pursuaded Congress to open the federal courts to women lawyers in 1879, and the first woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court. She was also active in working for women’s rights and overcame many social and personal obstacles related to gender restrictions. Lockwood ran for president in 1884 and 1888 on the ticket of the National Equal Rights Party and was the first woman to appear on official ballots.

Born Belva Ann Bennett on October 24, 1830 in Royalton, New York, she was the daughter of farmers Lewis Johnson Bennett and Hannah Green Bennett. By age 14, she was teaching at the local elementary school. At the age of 14 she taught in a rural school, chafing that she was paid half the salary of her male counterpart.

In 1848, when she was 18, Belva married Uriah McNall, a local farmer. McNall died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1853, three years after their daughter Lura was born. Widowed at 22 and refusing the traditional dependency of a widow, Belva separated from her child for nearly three years to attend college.

Belva’s plan, as she explained to Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, was not well-received by many of her friends and colleagues. Most women did not seek higher education, and it was especially unusual for a widow to do so. Nonetheless, she was determined and persuaded the administration at Genesee College in Lima, New York to admit her.

Career in Education

Graduating with honors from Genessee College in 1857 with a bachelor’s degree, Belva reclaimed her daughter and soon became the headmistress of Lockport Union School. It was a responsible position, but Lockwood found that whether she was teaching or working as an administrator, she was paid half of what her male counterparts were making. (Later Lockwood worked to equalize pay for educators.)

Belva stayed at Lockport until 1861, then became principal of the Gainesville Female Seminary; soon after, she was selected to head a girls’ seminary in Owego, New York where she stayed for three years. Her educational philosophy gradually changed after she met women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony.

Anthony had progressive ideas about society’s restrictions on women and was concerned about the limited education girls received. Courses at most girls’ schools chiefly prepared female students for domestic life or for temporary work as teachers. Anthony believed that young women ought to be given more options, including preparation for careers as businesswomen, where they could receive much better pay.

Belva was encouraged by Anthony to make changes at her schools. She expanded the curriculum and added courses typical of those which young men took, such as public speaking, botany and gymnastics. Lockwood decided to study law rather than continue teaching.

Shortly after the end of the Civil War, Belva sent her 16-year-old daughter to be educated at her alma mater, Genessee College. Belva then moved to Washington, DC in search of opportunity. While exploring the study of law she earned her living as a rental agent, newspaper correspondent, sales representative and lecturer.

In 1868, Belva remarried to Reverend Ezekiel Lockwood, a much older man who was a Civil War veteran, Baptist minister and practicing dentist. They had a daughter Jessie, who died before her second birthday. Reverend Lockwood had progressive ideas about women’s roles in society. He encouraged his wife to study law.

In 1870 Belva Lockwood applied to the Columbian Law School in the District of Columbia. The trustees refused to admit her as they believed she would be a distraction to male students. She was finally accepted at the new National University Law School. Although she completed her studies in May 1873, the school was unwilling to grant a diploma to a woman. Without a diploma, Lockwood could not gain admittance to the bar.

In September 1873 Lockwood wrote a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant, appealing to him for justice, stating she had passed all her courses and deserved to be awarded a diploma. A week after sending the letter, Lockwood received her diploma at age 43.

Legal Career

Lockwood was admitted to the District of Columbia bar, becoming one of the first female lawyers in the United States. Several judges stated that they had no confidence in her, a reaction she repeatedly had to overcome. When she tried to gain admission to the bar in Maryland, a judge told her that God Himself had determined that women were not equal to men and never could be. When she tried to respond, he had her removed from the courtroom.

Although Lockwood’s husband supported her, under the law she was regarded as subordinate to her husband. In many states, a married woman could not individually own or inherit property, nor did she have the right to make contracts or to keep money she earned unless her husband permitted it. Judges used her marital status to deny her access to the courts.

Lockwood opened a small law office out of her home and initially worked with her husband Ezekiel, who had given up dentistry and was earning fees as a court-appointed guardian, overseeing the finances of minors and the mentally ill. He did not make a great deal of money in these endeavors, but he helped the family get by and opened doors for his wife.

In the small world of Washington, his name became known, and so did hers as she learned judicial and administrative procedure through copying and filing clients’ documents. After securing a place for himself, Ezekiel introduced his wife to officials and by 1873 she was also earning fees as a court-appointed guardian. As an agent, Ezekiel also pursued land and treaty claims on behalf of Native American clients. This work opened yet another area of law to his wife.

Lockwood began to build a practice and won some cases. Even her detractors began to regard her as competent. Lockwood had tremendous drive and loved the fact that law was a man’s game and believed that it could be “a stepping stone to greatness.”

Lockwood became active in the fight for equal rights for women. She lobbied for an 1872 bill that would give federal employees the same salaries, no matter their gender; the measure passed. She testified before Congress in support of legislation to give married women and widows more protection under the law. She was active in several women’s suffrage organizations, fighting for women’s voting rights.

Until 1875 the Lockwoods ran Belva’s practice out of their modest home at the Union League Hall in downtown Washington. The office drew a multiracial clientele of laborers, painters, maids, tradesmen, veterans and owners of small real estate properties. The fact that her clients were largely working class undoubtedly helped in her success.

Half of her courtroom work involved divorce actions. As a woman attorney, she attracted female clients and represented wives as complainants against defendant husbands. And from 1875 to 1885 Belva represented at least 69 criminal defendants who were charged with virtually every category of crime from mail fraud and forgery to burglary and murder.

In 1875 the Lockwood family took rooms in a house at 512 10th Street. Belva conducted business in one or two of these rooms with Lura and Ezekiel nearby. Lockwood soon found herself the primary breadwinner as her husband’s health began to fail. Lockwood later spoke of her life’s hard lessons, repeatedly urging men and women to support education for girls so they would not be dependent on others.

Ezekiel Lockwood died in late April 1877. The widow grieved but did not adopt deep mourning. Five days after his death, she was back at her desk.

Three months later Belva purchased the house at 619 F Street, NW. Although it was not fancy, the 20-room house made an impression on visitors. Heavily mortgaged, it was undeniably a risky venture, but the purchase made good business sense. There she housed her law practice, her daughter and various members of her extended family. Spare rooms were rented out. She would use the property as collateral on loans and business deals.

Lockwood practiced law in the fashion of Washington men – with small, street-level firms, her days a busy mix of clients, paperwork and court appearances. Male attorneys in Washington came to consider her a proper colleague, and some shared case work.

Lockwood’s daughter Lura and her niece Clara Bennett began play important roles as Lockwood’s legal assistants. The day-to-day law practice of mostly pension and land claims was handled by them. Belva was the ‘rainmaker’ for the family firm, attracting clients through her travels and lectures, writing the briefs and conducting the trials for the occasional high profile case.

In 1876, the justices of the US Supreme Court had refused to admit Lockwood to its bar, stating, “none but men are permitted to practice before [us] as attorneys and counselors.” Lockwood drafted an anti-discrimination bill to have the same access to the bar as male colleagues. From 1874 to 1879, she lobbied Congress to pass it.

On March 3, 1879, Congress finally passed the law, which was signed by President Rutherford B. Hayes. It allowed all qualified women attorneys to practice in any federal court. Lockwood became the first woman member of the U.S. Supreme Court bar, sworn in amidst “a bating of breath and craning of necks.” In 1880, she argued a case, Kaiser v. Stickney, before the high court, the first woman lawyer to do so.

Career in Politics

Belva Lockwood was also the first woman to run for President of the United States, running as the candidate of the National Equal Rights Party in 1884 and 1888. She told voters that she would improve the rights of women and minorities. While not a serious contender in either race, Lockwood helped inform a wide audience about issues important to her.

Representing a third party without a broad base of support, Lockwood did not have a serious chance of winning the presidency. She could not vote, she told reporters, but nothing in the Constitution prevented men from voting for her. In an 1884 article, the Atlanta Constitution warned male readers of the dangers of “petticoat rule”. She won fewer than 5,000 votes in 1884 but was not discouraged.

On January 12, 1885, Lockwood petitioned the US Congress to have her votes counted. She told newspapers and magazines that she had evidence of voter fraud. She asserted that supporters had seen their ballots ripped up and that she had “received one-half the electoral vote of Oregon, and a large vote in Pennsylvania, but the votes in the latter state were not counted, simply dumped into the waste basket as false votes.” Nothing was done.

Still, Lockwood was very pleased with her efforts. Her campaign had generated enormous publicity, opportunities to travel, large audiences who paid to hear her speak, and almost five thousand votes. She even made a small profit. Success prompted her to try again in 1888 but this campaign produced more disapproval and less satisfaction.

Late Years

If the docket books are to be trusted, Belva eased out of courtroom work in the mid-1880s. She did not refuse civil and criminal trial work, but either the money was not sufficient, or her increasingly long trips as a public speaker – a second career that she had cultivated after her first presidential campaign – made it difficult to attract clients.

Lockwood was a well-respected writer, who frequently wrote essays about women’s suffrage and the need for legal equality for women. Among the publications in which she appeared in the 1880s and 1890s were Cosmopolitan (then a journal of current issues), the American Magazine of Civics, Harper’s Weekly and Lippincott’s.

In 1894 Belva Lockwood lost her beloved daughter Lura, who had been her mother’s assistant in her legal practice and her constant companion. Lura had married a pharmacist and left behind a son who Belva continued to raise. After Lura’s early death at age 44, Belva’s law practice disintegrated.

In 1906, in a multiparty case, she continued to represent the Eastern Cherokee regarding money owed to them by the US government. In one of her most famous cases, she made a successful argument before the US Supreme Court and won a $5 million settlement for the Cherokee people.

A woman of great energy, at the age of 83 Lockwood led a group of women on a tour of Europe. Until her final illness, she was marching on the streets of the capital in support of women’s suffrage and international peace. She told a reporter that a woman might one day occupy the White House: “It will be entirely on her own merits, however. No movement can place her there simply because she is a woman.”

Belva Lockwood died on May 19, 1917 at the age of 86, and was buried in Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC.

Throughout her life, Belva Lockwood spoke out on important issues, such as equal rights, minority rights and suffrage, and fought hard as a force for social change. She always insisted on the right to prove herself, and by the end of the 19th century, she had become one of the best known women in America.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Belva Ann Lockwood

Biography.com: Belva Lockwood

Belva Lockwood: Blazing the Trail for Women in Law

Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would be President