Doctor and Educator in the Civil War Era

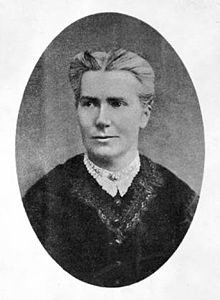

Emily Blackwell (1826–1910), physician and educator, was the second woman to earn a medical degree at what is now Case Western Reserve University, and the third woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. Dr. Blackwell, with her sister Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and their colleague Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, the first hospital for women and children in the United States.

Emily Blackwell (1826–1910), physician and educator, was the second woman to earn a medical degree at what is now Case Western Reserve University, and the third woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. Dr. Blackwell, with her sister Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and their colleague Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, the first hospital for women and children in the United States.

Early Years

Emily Blackwell was born on October 8, 1826, the sixth of nine surviving children born to Samuel and Hannah Lane Blackwell in the seaport of Bristol, England. There Samuel prospered as the owner of a sugar refinery, which provided a comfortable existence for his large, close-knit family.

Both Samuel and his wife had fairly liberal views toward education. During an era when girls were expected to master only the subjects that prepared them to be good wives and mothers, the Blackwells saw to it that their daughters as well as their sons studied mathematics, science, literature and foreign languages.

Emily especially liked to roam the fields around Bristol, observing plant and animal life. This provided the foundation for her subsequent passion for botany and ornithology. Emily became an amateur expert on the subject of birds and flowers, mostly through extensive reading and observations made near the family home.

In 1832, an economic downturn in England all but destroyed Samuel’s business. He and Hannah decided to make a fresh start in the United States. The family at first lived in New York City, where Samuel opened a sugar refinery. Within a year or so they moved across the Hudson River to Jersey City, New Jersey.

There they quickly became involved in the growing antislavery movement. Over the years family members developed close friendships with some of the country’s most prominent abolitionists, including journalist and reformer William Lloyd Garrison, clergyman Lyman Beecher, his son Henry Ward Beecher and his daughter Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Fire destroyed Samuel’s sugar refinery in 1836, leaving the Blackwells deeply in debt. Two years later, Samuel moved his family to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he hoped to start a refinery operation that made use of sugar beets instead of cane sugar. But his health worsened, and he died in August 1838.

Once again, the Blackwells found themselves in dire straits. But by 1845, they had paid off most of their debts, freeing Elizabeth to pursue her goal of becoming a doctor. After applying to and receiving rejections from 28 different medical schools, she was finally accepted by Geneva Medical College in Geneva, New York in 1847.

Meanwhile, Emily was struggling to find her own way in life. Bookish and painfully shy, she led a quiet, solitary existence of work and study that masked her growing sense of frustration and unhappiness. She desperately wanted to follow in her sister’s footsteps and enter the medical field but was plagued by self-doubt.

Instead, she tried teaching and found that she thoroughly detested it. As she confided to her diary around this time, according to writer Ishbel Ross in the book Child of Destiny:

I long with such an intense longing for freedom, action, for life and truth. I feel as though a mountain were on me, as though I were bound with invisible fetters. I am full of furious bitterness at the constraint and littleness of the life that I must lead…

Elizabeth Blackwell graduated from medical school at the head of her class in 1849, the first woman to earn a medical degree in the U.S. or Europe. After some additional study in Europe, she returned to the United States in 1851 and established a private clinic in New York City. A hard act to follow, but Emily was more determined than ever to become a doctor too.

Medical School

The fact that her famous sister had forged a path into medicine before her did not make Emily’s entry into the profession any easier. Her application for admission was eventually rejected by twelve medical schools simply because she was a woman – including Geneva Medical College, her sister’s alma mater.

However, Emily Blackwell was not deterred. In 1852 she was finally accepted at Rush Medical College in Chicago. During the summer before classes began, she lived with Elizabeth in Jersey City and obtained visiting privileges at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, where she was able to gain valuable experience just walking the wards.

However, when the trustees at Rush came under pressure by the Illinois state medical board to expel Emily because of her gender, they discontinued her studies at the end of her first year. But she persevered and was finally accepted at the Western Reserve University medical school in Cleveland, Ohio, where she earned her medical degree in 1854, becoming the second woman to earn an M.D. degree at that school and the third woman to earn a medical degree in the United States.

At Western Reserve, the medical education of women had begun at the urging of Dean John Delamater, who was backed by the Ohio Female Medical Education Society, formed in 1852 to provide moral and financial support for women medical students. Despite their efforts, the Western Reserve faculty voted to put an end to Delamater’s policies in 1856, finding it “inexpedient” to continue admitting women.

After graduating with the highest honors, Emily went to Europe for two years to do postgraduate work in England, France and Germany. First, she went to Edinburgh, Scotland, to study obstetrics and gynecology for a year with Sir James Young Simpson. She so impressed him that he recommended her to several of Europe’s most important clinics. Simpson noted in a letter that he had rarely met a young physician as well versed in literature, science and medical practice.

Medical Career

In 1856 Dr. Emily Blackwell returned to New York City where her sister Elizabeth was still fighting to gain acceptance among her fellow physicians and potential patients, most of whom looked upon female doctors with a great deal of suspicion, if not outright hostility.

Elizabeth had established a dispensary to treat poor women and children, but her ultimate dream was to expand it into a full-fledged hospital where women could consult a doctor of their own sex about female health problems and where training was available for women interested in becoming doctors.

In 1857 the Blackwell sisters, along with another Western Reserve graduate Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in a poor neighborhood that was home to a large immigrant population of Germans, Italians and Slavs. It was the first hospital dedicated to serving women and children in the United States and the first hospital staffed entirely by women.

The doctors worked diligently to maintain the highest medical standards while quietly overcoming the prejudices and fears of those they had vowed to serve as well as those who were keeping a close eye on their project. Before long, other women with an interest in medicine were coming to the infirmary to work as interns, nurses and pharmacists.

While Elizabeth served as the director and Dr. Zakrzewska was the resident physician, Emily devoted herself entirely to patient care. By all accounts, she was an excellent physician and surgeon. Emily also performed surgery, because her sister’s vision had been badly damaged by an eye infection. Patients were charged according to their ability to pay; four dollars a week if they could afford it, less if they could not. The most destitute paid nothing at all.

Emily also proved to be an able administrator and fundraiser. In 1858, the elder Dr. Blackwell went to Europe for a year and Zakrzewska moved to Boston, leaving Emily to run the Infirmary. During this time she was successful in getting state funding for their hospital, and the number of patients increased to the point where the operation had to move to larger quarters in 1860.

After Elizabeth’s return, the sisters also expanded the scope of their efforts by launching the first in-home medical social work program in the United States, visiting the poor where they lived to offer basic health care and lessons in proper sanitation.

In 1859, after a brief tour in England to campaign for the medical education of women, Blackwell raised $50,000 toward starting a medical school. In 1860 the Infirmary began to train a few young women as assistant physicians. Since established hospitals would not allow female doctors onto the wards, the Infirmary was almost the only place female physicians in training could get any practical experience.

And when the Civil War erupted in 1861, Dr. Emily Blackwell helped organize the Women’s Central Association of Relief, which recruited and trained women who had volunteered to serve as nurses for the Union army. She and Mary Livermore also played an important role in the development of the United States Sanitary Commission.

After the war ended, the Blackwells attempted to convince medical schools to admit women who had had some training at the Infirmary. In 1868, when it became clear that would not happen, the Blackwell sisters established the Women’s Medical College for the education of female physicians in New York City. Elizabeth was professor of hygiene, while Emily taught obstetrics and women’s diseases.

In 1869, Elizabeth moved back to England permanently to continue the work she had begun there a decade earlier. Emily then took charge of both the infirmary and the school, serving not only as a physician but also as dean of the college for the next thirty years. In 1871, she accepted membership in the New York County Medical Society.

During the 1870s, having finally gained confidence in her abilities as both a physician and a hospital administrator, Dr. Blackwell became more visibly active in the growing social reform movement. In that role, she tackled issues such as prostitution, sex education and alcohol abuse.

During that time, Dr. Blackwell also managed the infirmary – overseeing surgery, nursing and bookkeeping. She traveled to the state capital of Albany to convince the legislature to provide the hospital with funds that would ensure long-term financial stability. She transformed an institution housed in a rented, sixteen-room house into a fully fledged hospital. By 1874 the infirmary was serving over 7,000 patients annually.

The Women’s Medical College quickly rose to the front rank of America’s medical institutions. Known for its exceptionally high standards among medical schools in general, the college expanded from a two-year program to a three-year institution in 1876, and Dr. Blackwell moved the school into more spacious quarters.

In 1893 it became the first four-year medical program in the nation. Many male medical schools at the time were still offering only two years of study. A year later, a comprehensive training course for nurses was established.

In 1899, after Cornell University Medical College began accepting female students on an equal basis with men, Dr. Blackwell arranged for the transfer of her students to Cornell. During its thirty-one year existence, the Women’s Medical College trained 364 women doctors.

Late Years

Dr. Emily Blackwell then retired from the college and practice of medicine and left the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in the hands of its very capable staff. Some 150 years after its founding, the facility continues to operate as the NYU Downtown Hospital.

Since 1883, Dr. Blackwell had been living with her partner Dr. Elizabeth Cushier, another doctor at the Infirmary. In 1900 at the age of 74, Blackwell traveled with Cushier in Europe for eighteen months. Blackwell then divided her time between her winter home in Montclair, New Jersey, and a summer cottage in York Cliffs, Maine, both of which she shared with Dr. Cushier.

Emily saw her sister Elizabeth one last time during the summer of 1906 when Elizabeth visited the United States. The following year, the elder Blackwell fell down a flight of stairs while vacationing in Scotland; she never fully recovered from the accident and suffered a stroke in May 1910.

Emily Blackwell survived only a few months longer, dying of enterocolitis (inflammation of the small and large intestines) on September 7, 1910 at her summer home in York Cliffs, Maine.

By carrying on the work she and her sister Elizabeth had begun together, Dr. Emily Blackwell helped pave the way for countless other women who were interested in pursuing careers in medicine. Those who knew her described her as a superb practitioner and an inspirational teacher. The high standards Blackwell set for herself and her students were in large part responsible for opening the medical field to women and convincing a skeptical public to accept female physicians.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Emily Blackwell

Gale Encyclopedia of Biography: Emily Blackwell

Changing the Face of Medicine: Dr. Emily Blackwell