Abolitionist, Writer and Social Reformer

Frances Wright (1795–1852) was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, feminist, abolitionist and social reformer who became a U.S. citizen in 1825. That year she founded the Nashoba Commune in Tennessee as a Utopian community to prepare slaves for emancipation, but it lasted only three years. Her Views of Society and Manners in America (1821) brought her the most attention as a critique of the new nation.

Childhood

Frances Wright was born September 6, 1795, one of three children born in Dundee, Scotland to Camilla Campbell and James Wright, a wealthy linen manufacturer and political radical. Both of her parents died young, and Fanny (as she was called as a child) was orphaned at the age of three, but left with a substantial inheritance.

An aunt acted as guardian for both Frances and her sister Camilla. Wright was brought up in the homes of relatives, including James Milne, a member of the Scottish school of progressive philosophers. Milne, who encouraged Fanny to question conventional ideas, was to have a lasting influence on her development.

At age 16, Fanny returned to Scotland and spent her winters studying and writing, and her summers visiting the Scottish Highlands. She educated herself from a college library, and by the age of 18, she had written her first book.

In the United States

In 1818 Frances and Camilla Wright came to New York where Frances produced a play she had written named Altorf about the struggle for Swiss independence. After returning to England Wright wrote Views of Society and Manners in America (1821) and A Few Days in Athens (1822). In Views of Society Wright praised America’s experiments in democracy, and hailed American life as progressive in contrast to the backwardness of the Old World.

In 1821, Wright went to France to meet Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette who had invited her there after reading some of her work. When Lafayette came to America in 1824, Wright and his sister Camilla traveled with him, but not as official members of his delegation. They were with Lafayette when he was entertained at the homes of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Since she was not part of the official delegation, Wright was free to move about on her own and traveled the U.S. extensively. While traveling down the Mississippi, she was appalled by the practice of slavery. She wrote: “The sight of slavery is revolting everywhere. But to inhale the impure breath of its pestilence in the free winds of America is odious beyond all that imagination can conceive.”

Later that year Wright visited New Harmony on the Wabash River in southwest Indiana where Robert Owen and his son Robert Dale Owen were trying to establish a Utopian society. Owen believed that communal living would enable people to live happier, more economical and more productive lives.

Nashoba Commune

As a result of this visit, Wright decided to establish a colony in which slaves could be emancipated. She believed that slaves would work harder for their freedom than they would for a master, and therefore expected the colony to be self-supporting and to provide funds for the purchase and training of additional slaves.

Wright submitted to Lafayette a plan for buying slaves, without loss to their owners, followed by life in a colony where they would be educated and prepared for freedom. This plan was discussed with former Presidents Jefferson, Madison and James Monroe and encouraged by Lafayette. Lafayette recommended Frances Wright also visit Senator Andrew Jackson.

Jackson agreed to help Wright find suitable land and slaves and suggested that she acquire land in the new Chickasaw purchase, approximately fifteen miles east of Memphis, Tennessee, which Jackson and his partners had founded six years earlier. It was decided that this area would be the best place for emancipation because public feeling there was more favorable to abolition than elsewhere in the South.

Wright arrived in Memphis in late October 1825, and inspected land along the Wolf River near the site of present-day Germantown. She then went to Nashville and bought eleven slaves including five men (Willis, Jacob, Gradison, Redick and Henry), three women (Nelly, Peggy and Kitty) and three of their children.

On her return to Memphis Wright bought 1,940 acres of land on the Wolf River, thirteen miles from Memphis. She described it as “2000 acres of good and pleasant woodland, traversed by a good and lovely stream (Wolf River), communicating 13 miles below with the Mississippi at the old Indian trading post of Chickasaw Bluffs.”

Frances Wright was only 30, she was rich and was applauded in Europe as well as the United States. Many approved her ideas because she offered a way to prepare slaves to be self-supporting citizens, while saving the South from the shock of the sudden loss of millions of dollars of investment in slaves.

In later 1825 Wright established her experimental settlement and named it Nashoba, the Chickasaw word for the Wolf River. While her focus was on communal living for soon-to-be emancipated slaves, she announced that Nashoba welcomed anyone who was willing to work for the common good. She envisioned a self-sustaining multi-racial community composed of slaves, free blacks and whites.

Three men played important roles in the experiment: Richeson Whitby, a shy Quaker from Robert Owen’s New Harmony community; a Scotsman by the name of James Richardson, who lived in Memphis and had strong convictions concerning moral freedom; and George Flowers, an emancipationist with experience in Utopian community living.

Though she was tall and walked with a manly stride, Wright was unaccustomed to physical labor. She worked beside the slaves clearing trees, burning the underbrush, building cabins and planting an orchard. These tasks put calluses on her hands, weathered her complexion, exhausted her strength long before sundown, and exposed her to the fevers of the land in the river bottom.

Frances Wright was inexperienced in the necessities of life in the wooded frontier, and found it difficult getting labor from illiterate workers, squelching quarrels among the field hands and distinguishing illness from laziness.

In December 1826 Wright deeded the property to a group of trustees under a deed of trust. The trustees were General Lafayette, William McClure, Robert Owen, Robert Dale Owen, C.D. Colden, Richeson Whitby, Robert Jennings, George Flowers, her sister Camilla Wright and James Richardson.

The physical work eventually broke Frances Wright’s health. She became seriously ill with malaria and was encouraged to seek the milder climate of Ohio in May 1827. Her sister Camilla and Richeson Whitby were left in charge, with the help of James Richardson.

While Frances was away, Camilla and Whitby fell in love and married, and passed the sterner tasks of leadership on to James Richardson who took control of Nashoba’s policies. Critics believe that with Richardson at the helm, the Nashoba Experiment drifted from its original course of emancipation into a dangerous pool of radical ideas on communal living and moral unconventionalities.

Frances Wright went to Europe to improve her health and there recruited Frances Trollope, an English travel writer. The two women returned through the port of New Orleans and up the river to Memphis, arriving at Nashoba in January 1828. By that time, the community had collapsed financially.

Trollope was shocked by manners in Memphis, dismayed by the desolation at Neshoba and appalled by the primitive room in which she and Wright lived. Trollope disdained the poor diet of pork and rice, without any other meat or vegetable, and no milk, butter or cheese; rain water was the only liquid. She remained a few days and then went on to Cincinnati.

The plantation seem doomed to failure. Whitby’s health failed and he moved with Camilla to Ohio. Frances Wright, unable to remain at Nashoba herself, was forced to admit defeat after an attempt to operate the place with a hired overseer proved disastrous. Fighting gossip, criticism and poor health, Wright was forced to abandon Nashoba after spending her entire personal fortune on the project.

Her plan had been to have five years of preparation prior to emancipating the slaves she had purchased, then to establish a colony of Nashoba-trained men and women in Africa. The reality was that five years after she came to Memphis, she put 30 former slaves and 18 of their children on a flatboat for New Orleans.

Wright then chartered a vessel named the John Quincy Adams, and sailed to the black republic of Haiti in January 1830 with the Nashoba slaves, who were placed under the Haitian President’s supervision on one of his estates and supplied with tools and provisions. If they became productive citizens, the former slaves were to be given land grants.

Political Activities

Frances Wright then moved to New York where she worked with Robert Dale Owen to publish the Free Enquirer. In the journal Wright called for improvements in the status of women, including equal education, universal suffrage, legal rights for married women, liberal divorce laws and birth control.

She then focused on education reform, advocating a system of free state boarding schools in which children would be educated without religious doctrine but receive training in traditional subjects as well as industrial skills. Her ideal of universal education gave a voice to those women who wanted more education for themselves as well as their children.

From her desire to see these educational proposals enacted, Frances Wright moved in the political sphere and became a central figure in the workingmen’s movement, which consisted of activism by small farmers, artisans and workers in early factories concerning the gulf between the classes and the capitalistic system itself.

Women were particularly affected as they became more confined to home duties as industry shifted away from the home into the city. Wright and Owen also became involved in the radical Workingmen’s Party while living in New York. Those opposing the movement referred to it as the Fanny Wright Party.

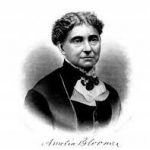

Dubbed “The Great Red Harlot” for her personal life, which included several illicit romances, Wright also developed her own dress code for women. This included bodices, ankle-length pantaloons and a dress cut to above the knee. This style was later promoted by feminists such as Amelia Bloomer, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In 1831 Wright married a French physician, Guillayme D’Arusmont, and moved to France and spent time out of the public eye. They had one child: Frances Sylva D’Arusmont in 1832.

When she returned to the States she resumed a political platform with a historical perspective narrating the ills of contemporary society. Wright’s ideology, the workingmen’s movement and the women’s movement converged in the Popular Health Movement of the 1830s, and sought to give women a larger role in health and medicine.

In 1836 she published her last book, Course of Popular Lectures, in which she once again advocates the rights of women:

However novel it may appear, I shall venture the assertion, that, until women assume the place in society which good sense and good feeling alike, assign to them, human improvement must advance but feebly. It is in vain that we would circumscribe the power of one half of our race, and that half by far the most important and influential. If they exert it not for good, they will for evil; if they advance not knowledge, they will perpetuate ignorance. Let women stand where they may in the scale of improvement, their position decides that of the race.

Wright’s marriage was not a success. Her husband, D’Arusmont gained control of her entire financial resources, including her earnings from lectures and the royalties from her books. After a lifetime of struggling for high ideals, she spent the last years of her life trying to settle her financial affairs and a complicated divorce.

After the midterm campaign of 1838, Frances Wright began to suffer from a variety of health problems.

Years later, she was still embroiled in legal struggles with D’Arusmont when she broke her hip in a fall on an icy staircase in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Frances Wright died from complications resulting from that fall on December 13, 1852. She was 57 years old.

So great was Frances Wright’s national recognition as a public figure, through her political activities, William Cullen Bryant wrote an ode to her while he was editor of the Evening Post. She had expressed through her projects in America what French Utopian socialist Charles Fourier had said, “that the progress of civilization depends on the progress of women.”

As requested, Wright’s tombstone in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery was inscribed with the words:

I have wedded the cause of human improvement, staked on it my fortune, my reputation and my life.

The heir to Wright’s property in Ohio and Tennessee was her daughter Frances Sylva D’Arusmont.

Ernestine Rose Speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1858:

Frances Wright was the first woman in this country who spoke on the equality of the sexes. She had indeed a hard task before her. The elements were entirely unprepared. She had to break up the time-hardened soil of conservatism, and her reward was sure – the same reward that is always bestowed upon those who are in the vanguard of any great movement. She was subjected to public odium, slander and persecution. But these were not the only things she received. Oh, she had her reward – that reward of which no enemies could deprive her, which no slanders could make less precious – the eternal reward of knowing that she had done her duty.

SOURCES

Spartacus schoolnet: Fanny Wright

The Germantown Museum

Wikipedia: Frances Wright

Frances Wright, Woman’s Advocate

In the book titled “A peoples’s History of the United States” author’s name is Howard Zinn, on page 120, he writes that Frances Wright wanted free public education for all chidren from the age two and over, in state-supported boarding schools.