One of the Top Women Poets in the United States

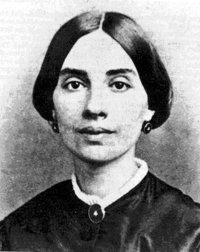

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) is considered the most original 19th century American poet. She is noted for her unconventional broken rhyming meter and use of dashes and random capitalization as well as her creative use of metaphor and overall innovative style. She was a deeply sensitive woman who explored her own spirituality, in poignant, deeply personal poetry, revealing her keen insight into the human condition.

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) is considered the most original 19th century American poet. She is noted for her unconventional broken rhyming meter and use of dashes and random capitalization as well as her creative use of metaphor and overall innovative style. She was a deeply sensitive woman who explored her own spirituality, in poignant, deeply personal poetry, revealing her keen insight into the human condition.

Image: A photo dated 1860 believed to be Emily Dickinson

Emily the Daughter

Emily Dickinson was born December 10, 1830 in Amherst, Massachusetts. She was the second child born to Emily Norcross and Edward Dickinson, a Yale graduate, successful lawyer and United States Congressman. While Emily described her father in a warm manner, her correspondence suggests that her mother was cold and aloof. Emily and her family lived with her grandfather Samuel Dickinson and his family in Amherst. In 1840 the Dickinsons moved to North Pleasant Street.

Emily was troubled from a young age by a fear of death, especially the deaths of those who were close to her. When her second cousin and close friend Sophia Holland died in April 1844, Emily was traumatized. She became so melancholic that her parents sent her to stay with family in Boston to recover.

The Dickinsons were strong advocates for education and Emily received an early education in classic literature, mathematics, history and botany. At age ten Emily entered Amherst Academy and studied there for seven years. At age seventeen, she enrolled at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley about ten miles from Amherst, but was so homesick she returned home after one year.

In 1848, back in the family home in Amherst, Emily wrote her first poems. She was also in the midst of the college town’s society and bustle although she started to spend more time alone, reading and maintaining lively correspondences with friends and relatives.

When she was eighteen, Dickinson’s family befriended a young attorney by the name of Benjamin Franklin Newton. Although their relationship was probably not romantic, Newton’s gift to her of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s first book of collected poems had a liberating effect. Newton believed in Emily and recognized her as a poet.

Dickinson was also familiar with contemporary popular literature, and was influenced by Lydia Maria Child‘s Letters from New York, another gift from Newton. When he was dying of tuberculosis, Newton wrote in a letter that he would like to live until Emily achieved the greatness he foresaw.

During the 1850s, Emily’s strongest and most affectionate relationship was with Susan Gilbert, an old schoolmate from Amherst Academy. Emily sent her over 300 letters over the course of their friendship. Susan was supportive of the poet, playing the role of “most beloved friend, influence, muse and adviser” whose editorial suggestions Dickinson sometimes followed.

Until 1855, Dickinson had not strayed far from Amherst. That spring, accompanied by her mother and sister, she took one of her longest and farthest trips away from home. First, they spent three weeks in Washington, DC, where her father was representing Massachusetts in Congress. Then they went to Philadelphia for two weeks to visit family.

The same year her father bought The Homestead, the Main Street house where Emily was born. He built an addition to the mansion with extensive gardens and a conservatory.

In 1856 Susan married Emily’s brother Austin, now a successful Amherst lawyer, after a four-year courtship. Emily’s father built a house for him and Susan called The Evergreens, which stood on the west side of The Homestead, but their marriage was not a happy one.

From the mid-1850s, Emily’s mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Emily said that she would visit if she could leave “home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her”.

As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson’s domestic responsibilities weighed more heavily upon her. Forty years later, Lavinia stated that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Emily took this role as her own, and “finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it.”

Emily the Poet

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican, and his wife Mary. They visited the Dickinsons regularly for years to come. During this time Emily sent him over three dozen letters and nearly fifty poems. Their friendship brought out some of her most intense writing and Bowles published a few of her poems in his journal.

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Emily began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, between 1858 and 1865 she made clean copies of her work in carefully pieced-together manuscript books. The first half of the 1860s proved to be Dickinson’s most productive writing period.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was a captain in the 51st Massachusetts Infantry during the early part of the Civil War. From November 1862 to October 1864, when he was retired because of a wound received in the preceding August, he was colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers – a Union Army regiment of escaped slaves from South Carolina and Florida.

In April 1862, Higginson, a literary critic and radical abolitionist published an article in the Atlantic Monthly, titled “Letter to a Young Contributor,” which contained practical advice for those wishing to break into print. Dickinson’s decision to contact Higginson suggests that she was contemplating publication and that it may have become increasingly difficult to write poetry without an audience.

Emily Dickinson sent a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, enclosing four poems and asking:

Mr Higginson,

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The Mind is so near itself – it cannot see, distinctly –

and I have none to ask – Should you think it breathed –

and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude –

I enclose my name – asking you, if you please –

Sir – to tell me what is true?

His reply included gentle criticism of Dickinson’s odd verse, questions about her personal and literary background and a request for more poems. Higginson’s next reply contained high praise, but warned her against publishing her poetry because of its unconventional style. Gradually, Higginson became Dickinson’s mentor, though he almost felt out of her league. Emily may have also had romantic feelings for him.

Dickinson delighted in dramatic self-characterization and mystery in her letters to Higginson. She said of herself, “I am small, like the wren, and my hair is bold, like the chestnut bur, and my eyes like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves.” She stressed her solitary nature, stating that her only real companions were the hills, the sundown and her dog, Carlo.

His interest in her work certainly provided great moral support; many years later, Dickinson told Higginson that he had saved her life in 1862. They corresponded until her death, but her difficulty in expressing her literary needs left Higginson puzzled; he did not press her to publish in subsequent letters.

Emily in Seclusion

In 1864 and 1865 Emily went to stay with her Norcross cousins in Boston, where she underwent treatments for a painful eye condition. It was the last time she left Amherst. Soon after, her behavior began to change. She did not leave The Homestead unless it was absolutely necessary and as early as 1867, she began to talk to visitors from the other side of a door rather than speaking to them face to face.

She was rarely seen, and when she was, she was usually clothed in white. Austin and his family began to protect Emily’s privacy, deciding that she was not to be a subject of discussion among outsiders. Her younger sister Lavinia, who also lived at home her entire life, and her brother Austin were not only family, but Emily’s intellectual companions. She also had a good rapport with the children in her life.

Dickinson’s poetry reflects her loneliness and the speakers of her poems generally live in a state of want, but her poems are also marked by the intimate recollection of inspirational moments which are decidedly life-giving and suggest the possibility of happiness.

Her work was heavily influenced by the Metaphysical poets of seventeenth-century England, and also admired the poetry of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, as well as John Keats. Though she was dissuaded from reading the verse of her contemporary Walt Whitman (because it was rumored to be disgraceful), the two poets are now considered the founders of a uniquely American poetic voice.

When Thomas Wentworth Higginson urged Emily to come to Boston in 1868 so that they could formally meet for the first time, she declined, writing: “Could it please your convenience to come so far as Amherst I should be very glad, but I do not cross my Father’s ground to any House or town.”

He came to Amherst in 1870 and they finally met. Later he referred to her, in the most detailed and vivid physical account of her on record, as “a little plain woman with two smooth bands of reddish hair… in a very plain and exquisitely clean white pique and a blue net worsted shawl.” He also felt that he never was “with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her.”

Family and Loss

By the early 1870s Emily’s ailing mother was confined to her bed and Emily and her sister cared for her. Lamenting her mother’s increasing physical as well as mental demands, Emily wrote that “Home is so far from Home.” Her father Edward died suddenly in 1874, and Emily stopped going out in public.

Although she continued to write in her last years, Emily stopped editing and organizing her poems. She also exacted a promise from her sister Lavinia to burn her papers. She regularly tended the Homestead gardens and loved to bake, and the neighborhood children sometimes visited her.

The 1880s were a difficult time for the remaining Dickinsons. Irreconcilably alienated from his wife, Austin fell in love in 1882 with Mabel Loomis Todd, an Amherst College faculty wife who had recently moved to the area. Austin distanced himself from his family as his affair continued and his wife became sick with grief.

Emily’s esteemed friend Charles Wadsworth died in 1882, the same year her mother succumbed to her long illness. Five weeks later, Emily wrote “We were never intimate Mother and children, while she was our Mother – but Mines in the same Ground meet by tunneling, and when she became our Child, the Affection came.” The next year Emily’s favorite nephew – Austin and Susan’s youngest child, Gilbert – died of typhoid fever.

As death succeeded death, Dickinson found her world upended. In the fall of 1884, she wrote that “The Dyings have been too deep for me, and before I could raise my Heart from one, another has come.”

Emily herself became ill with Bright’s Disease, a kidney ailment that causes chronic pain. She fainted one day while baking in the kitchen, and remained unconscious late into the night and weeks of ill health followed. She was confined to her bed for a few months, but managed to send a final burst of letters in the spring. What is thought to be her last letter was sent to her cousins, Louise and Frances Norcross.

Emily Dickinson died on May 15, 1886 at the age of 55. A gathering was held at The Homestead, and the funeral service was simple and short; Higginson read one of Emily’s favorite poems, “No Coward Soul Is Mine” by Emily Bronte.

At Emily’s request, her “coffin [was] not driven but carried through fields of buttercups” for burial in the family plot in the West Cemetery in Amherst, Massachusetts. She was buried in one of the white dresses she had worn in her later years, with violets pinned to her collar by Lavinia.

After Emily’s death her sister Lavinia found 40 handbound volumes of poetry, nearly 1800 poems in all. These booklets were made by folding and sewing five or six sheets of stationery paper and copying what seem to be final versions of poems that show a variety of dash-like marks of various sizes and directions. Some were written in pencil, only a few titled, many unfinished.

While Dickinson was extremely prolific as a poet and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. Although many friends including Helen Hunt Jackson had encouraged Dickinson to publish her poetry, only a handful of them appeared publicly before her death.

Lavinia enlisted the aid of Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd to edit the poems and roughly arrange them chronologically into collections: Poems, Series 1 in 1890, Poems, Series 2 in 1891, and Poems, Series 3 in 1896. The edits were aggressive in order to standardize punctuation and capitalization and some poems re-worded, but by and large it was a labor of love.

My Favorite Emily Dickinson Poem:

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.

SOURCES

Poets.org: Emily Dickinson

Wikipedia: Emily Dickinson

Biography of Emily Dickinson

Wikipedia: Thomas Wentworth Higginson

Hahahaha. A labor of love! Todd was sleeping with Austin and had a vendetta against Susan, Austin’s wife, who is barely mentioned here. Susan’s name was erased from many letters before they were published essentially erasing her and Emily’s relationship, which, upon realizing the erasures in the 90s was discovered to be a romantic one. Check out Wild Nights with Emily. A fictionalized film that portrays the characters with this discovery in mind.

I don’t know who that is a picture of but it sure isn’t Emily Dickinson.