Governing Body During the American Revolution

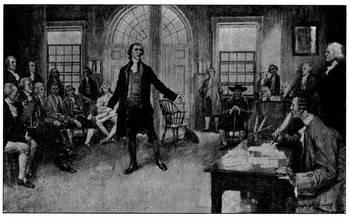

Image: First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was convened on September 5, 1774, in Carpenters Hall in Philadelphia, the largest city in America at the time. Fifty-six delegates appointed by the legislatures of twelve of the thirteen colonies attended this first meeting, which was in session between September 5 and October 26, 1774. Georgia did not send any representatives to the first Congress.

Background

The relationship between the Thirteen Colonies and the Kingdom of Great Britain had slowly but steadily worsened since the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. The war had plunged the British government deep into debt, prompting the Parliament to enact a series of measures to increase tax revenue from the colonies.

Many colonists, however, insisted that Parliament had no right to levy taxes upon them because they had no representatives in the British government, leading to the slogan “No taxation without representation.” Some colonial essayists went even further, and began to question whether Parliament had any legitimate jurisdiction in the colonies at all.

The First Continental Congress was called in response to the Intolerable Acts – a series of laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 relating to the American colonies. Benjamin Franklin had put forth the idea of such a meeting the year before but was unable to convince the colonies of its necessity until the British closed the Port of Boston.

Four of the acts were issued in direct response to the Boston Tea Party of December 1773; the Parliament hoped that by making an example of Massachusetts they could reverse the trend of colonial resistance that had begun with the 1765 Stamp Act. However, these acts only triggered the outrage that grew into the American Revolution.

First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress met from September 5 to October 26, 1774. The delegates included John Adams and Robert Treat Paine from Massachusetts, Thomas Lynch, Jr. and Edward Rutledge from South Carolina, and Philip Livingston and William Floyd from New York.

The Virginia delegation presented the most eminent group of men in America. George Washington, Richard Henry Lee, Edmund Pendleton, Benjamin Harrison V and Patrick Henry, who considered the government already dissolved, and was seeking a new system. Virginian Peyton Randolph was selected as President of Congress and presided over the proceedings.

Many of the delegates were initially unknown to one another and vast differences existed on some of the issues, but important friendships flourished. Frequent dinners and gatherings were held and were attended by all except the spartan Samuel Adams.

Pennsylvania delegate Joseph Galloway sought reconciliation with Britain, and put forth a Plan of Union of Great Britain and the Colonies, which proposed a popularly elected Grand Council which would represent the interests of the colonies as a whole, and would be a continental equivalent to the English Parliament. John Jay and other conservatives supported Galloway’s plan, but it was only supported by five colonies. (Galloway would later support the British).

Paul Revere then rode into town bearing the Suffolk Resolves, a series of political statements that had been forwarded to Philadelphia by a number of Boston-area communities. The resulting discussion further polarized the Congress. The radical elements eventually gained the upper hand, and a majority of the colonies voted to endorse the Resolves.

Accomplishments

The Congress had two primary accomplishments. The first was a compact among the colonies to boycott British goods. If the Intolerable Acts were not repealed, the colonies would also cease exports to Britain. The Continental Association was created by the Congress to implement the boycott, and committees of observation and inspection were to be formed in each colony.

The articles of the Continental Association imposed an immediate ban on British tea, and on importing or consuming any goods from Britain, Ireland and the British West Indies to take effect on December 1, 1774. Colonies would also cease all trade and dealings with any other colony that failed to comply with the bans. Imports from Britain dropped by 97 percent, but its potential was cut short by the outbreak of the Revolutionary War.

Declaration of Rights and Grievances

In October 1774, the Congress composed a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, as well as a plan of union and pleas to King George III to resolve the issues common to all of the colonies. The strategy was that the colonies would prepare for war while the Congress continued to pursue reconciliation.

The Declaration reads in part:

Whereupon the deputies so appointed being now assembled, in a full and free representation of these Colonies, taking into their most serious consideration the best means of attaining the ends aforesaid, do in the first place, as Englishmen their ancestors in like cases have usually done, for asserting and vindicating their rights and liberties, declare,

That the inhabitants of the English Colonies in North America, by the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the English constitution, and the several charters or compacts, have the following Rights:

1. That they are entitled to life, liberty, and property, and they have never ceded to any sovereign power whatever, a right to dispose of either without their consent.

2. That our ancestors, who first settled these colonies, were at the time of their emigration from the mother country, entitled to all the rights, liberties, and immunities of free and natural born subjects within the realm of England.

3. That by such emigration they by no means forfeited, surrendered, or lost any of those rights, but that they were, and their descendants now are entitled to the exercise and enjoyment of all such of them, as their local and other circumstances enable them to exercise and enjoy.

4. That the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council: and as the English colonists are not represented, and from their local and other circumstances, cannot properly be represented in the British parliament, they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved, in all cases of taxation and internal polity, subject only to the negative of their sovereign, in such manner as has been heretofore used and accustomed.

The First Continental Congress was regarded as a success by both the general public and the delegates. Despite heated and frequent disagreements, the delegates had come to understand the problems and aspirations of people living in the other colonies. Many of the friendships forged there would make the task of governing the new nation in the coming years much easier.

Second Continental Congress

The second major accomplishment of the First Congress was to provide for a Second Continental Congress in the event that their petition was unsuccessful in halting enforcement of the Intolerable Acts. Their appeal to the Crown had no effect, and so the Second Continental Congress was convened on May 10, 1775, shortly after the Battles of Lexington and Concord were fought in Massachusetts, marking the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The two bodies together comprise The Continental Congress.

John Hancock from Massachusetts was elected president of the assembly, and from May 1775 through 1781, the Second Continental Congress was our governing body. They organized the defense of the colonies and urged each colony to set up and train its own militia. On June 17, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill energized the Patriots, and the Congress established the Continental Army and appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief. A delegation from the colony of Georgia arrived in July.

The Olive Branch Petition was adopted by the Second Continental Congress in July 1775 in an attempt to avoid a full-blown war with Great Britain. The petition affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain and entreated the king to prevent further conflict. The petition was rejected, and on August 23, 1775, the king declared the colonies to be in a state of “open and avowed rebellion.”

Most delegates followed John Dickinson of Pennsylvania in his quest to reconcile with the king. However, a smaller group of delegates led by John Adams believed that war was inevitable. During the course of the Second Continental Congress, Adams and his group of colleagues decided the wisest course of action was to remain quiet and wait for the opportune time to rally the people.

This decision allowed John Dickinson and his followers to pursue whatever means of reconciliation they wanted. It was during this time that the idea of the Olive Branch Petition was approved. The Olive Branch Petition was first drafted by Thomas Jefferson, but John Dickinson found Jefferson’s language too offensive and rewrote most of the document, although some of the conclusion remained Jefferson’s.

Although the King discarded the petition, it still served a very important purpose in American Independence. The King’s rejection gave Adams and others who favored revolution the opportunity they needed to push for independence. The rejection of the “olive branch” polarized the issue in the minds of colonists and convinced to move towards independence.

The Second Continental Congress, which met from 1775 through 1781, went on to create the Declaration of Independence and many critical laws and provisions that established the United States of America.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Intolerable Acts

Wikipedia: Olive Branch Petition

Wikipedia: Continental Congress

The Coming of the American Revolution

USHistory.org: Proceedings of the First Continental Congress