Wife of Union General Abel Streight

Lovina McCarthy Streight (1830-1910) accompanied her husband, Union Brigadier General Abel Streight in the Western Theater throughout the Civil War. Streight is best known for Streight’s Raid through Tennessee and northern Alabama. His mission was foiled when CSA General Nathan Bedford Forrest surrounded the Union cavalry and took Streight and the majority of his brigade to Libby Prison, from which Streight later escaped. He was restored to his command and continued to serve for the balance of the war.

Lovina McCarthy Streight (1830-1910) accompanied her husband, Union Brigadier General Abel Streight in the Western Theater throughout the Civil War. Streight is best known for Streight’s Raid through Tennessee and northern Alabama. His mission was foiled when CSA General Nathan Bedford Forrest surrounded the Union cavalry and took Streight and the majority of his brigade to Libby Prison, from which Streight later escaped. He was restored to his command and continued to serve for the balance of the war.

Image: This portrait of Lovina McCarthy Streight hangs in the Indiana Statehouse

Lovina McCarthy was born 1830 in Steuben County, New York. Abel Streight was also born on June 17, 1828, in Steuben County, New York, but moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, as a young man. Lovina McCarthy married Abel Streight on January 14, 1849. They had one child, John Streight. By 1859 they were living in Indianapolis, Indiana, where Streight was a publisher of books and maps. He was also the author of The Crisis of Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-one in the Government of the United States, published in 1861.

When the Civil War broke out, Abel Streight joined the Union army in September 1861 as a colonel in the Fifty-first Indiana Infantry, which was attached to the Army of the Cumberland. Most wives in her situation waited at home for their husbands to return from war, but not Lovina. She accompanied her husband as he led his men south, bringing with her their five-year-old son.

Lovina witnessed several battles, nursed the sick and dying on the battlefield and in field hospitals. Her compassion and bravery earned her the title ‘Mother of the Fifty-first.’ During her wartime service, Confederate troops captured Lovina three times, twice exchanging her for prisoners. She reportedly escaped imprisonment a third time by brandishing a gun hidden in her skirts.

Streight’s Raid

Although he eventually attained the rank of Brigadier General, Abel Streight was not greatly successful as a military commander. In July 1862, Streight served as part of the Federal occupation force in northern Alabama. During this brief period, he routinely interacted with northern Alabama Unionists and recruited many into the Federal army, but greatly overestimated their numbers. This misconception, shared by many Federal military commanders and President Abraham Lincoln, jeopardized the planned Union raids months before they began.

In 1863, Colonel Streight proposed a plan to General James A. Garfield raise a force, including the Alabama Unionists, to make a raid into the South. Streight’s intention was to disrupt the Western & Atlantic Railroad between Chattanooga and Atlanta, which was supplying the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Garfield gave his permission.

Streight’s force was to include approximately 1700 troops mounted suitably for fast travel and attacks. However, due largely to war time shortages, Streight’s brigade were mounted on balky and unbroken mules recently procured from farms in western Tennessee, including two companies of Unionists in the 1st Alabama Cavalry (USA).

The rest of the regiment was serving under General Grenville Dodge out of Corinth, Mississippi, under General Ulysses S. Grant‘s Army of the Tennessee. Dodge’s mission was to screen Streight as he moved from Tennessee by boat, then overland across northern Alabama toward Georgia.

On April 19, 1863, Streight’s brigade boarded several boats at Nashville that transported the force southward on the Tennessee River and disembarked at Eastport, Mississippi. That night, a stampede scattered approximately 400 of the brigade’s mules into the surrounding countryside causing a delay as Streight waited in Eastport for a shipment of mules.

Two days later, on April 21, Streight rendezvoused with Dodge and his 8000 cavalrymen, and moved toward Tuscumbia, Alabama. During the march, skirmishers who had detached from CSA General Nathan Bedford Forrest‘s division impeded Federal movements.

Many of the mules Streight’s men were riding on were unbroken, old or incapable of carrying their riders for great distances without frequent stops. The Confederates hurled insults at the brigade, referring to them as the Jackass Cavalry. Amused onlookers, watching the soldiers riding mules through the countryside, embarrassed the men and slowed their movement.

As Streight left Tuscumbia late on April 26, a heavy rainstorm made the roads virtually impassable, forcing him to make an unscheduled stop at Mount Hope, Alabama. There, Dodge informed Streight that the two would not meet at Moulton, as previously planned. Dodge reported that his command had driven Forrest far to the north, thereby clearing a path for Streight to continue the raid unmolested.

Dodge’s movements, however, had not deterred Forrest. As Streight moved eastward, the morale of his command temporarily improved as dry weather and the capture of several Confederate supply wagons bolstered their spirits. The mood changed, however, when Union scouts spotted Confederates moving along both their right and left flanks, threatening to surround the entire command.

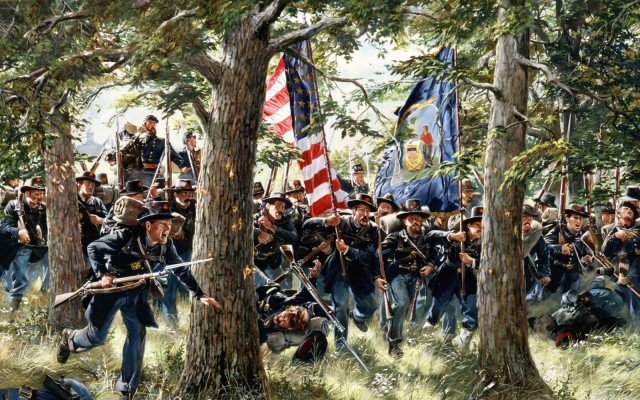

Streight’s brigade arrived at Sand Mountain, where he was intercepted by Forrest’s cavalry. During the Battle of Day’s Gap on April 30, 1863, Streight’s men thwarted Forrest’s attempt to surround him from the rear with a series of charges led by the Seventy-third Illinois and Fifty-first Indiana.

Undeterred, a few hours later Forrest resumed the attack upon Streight, whose men dismounted and occupied a ridge along Hog Mountain in preparation for what they believed was a larger force. Again Streight’s men repulsed several assaults and then resumed the march at an accelerated pace, which allowed them to ambush a portion of Forrest’s cavalry near Blountsville.

As Streight’s men pressed toward Gadsden, Alabama, Forrest’s constant presence behind the Union forces prevented Streight from resting his weary troops and mules, which proved too slow to outrun Forrest’s horsemen. And their constant braying enabled Forrest’s scouts to detect Streight’s force from more than two miles away.

On the afternoon of May 2, Streight crossed Black Creek (three miles from Gadsden) ahead of Forrest and burned the only nearby bridge, impeding the Confederate pursuit. Streight soon realized that his cavalry could not outrun Forrest for long, and he desperately needed to reach the city of Rome, Georgia. There, Streight intended to fight from behind some hastily prepared breastworks.

Unbeknownst to him, the actions of two local civilians thwarted his plans. Unable to use the bridge to cross the swollen Black Creek, Forrest rode to a nearby home to find a guide. He found 16-year-old Emma Sansom, with whose guidance he located a ford, crossed it, and caught up with Streight’s force.

Meanwhile, Gadsden resident John Wisdom raced 67 miles to Rome, where he warned residents of the approaching Union troops. As a result of his actions, Rome’s inhabitants repelled a detachment of Streight’s cavalry sent to occupy a vital bridge crossing the Coosa River, thus blocking the only available route into the city. Streight then turned west in search of another crossing, but eventually abandoned the search.

At Cedar Bluff, Alabama, Streight stopped for a much needed rest. Many of his cavalrymen had been walking due to the deaths of numerous mules. Forrest’s cavalry surrounded Streight and his 1700 raiders. Rather than face possible annihilation by what he believed to be a numerically superior foe, Streight surrendered his command on May 3, 1863.

During the negotiations, Forrest craftily reaffirmed Streight’s belief that the Confederates greatly outnumbered his brigade by having the Confederate cavalrymen repeatedly ride in circles in and out of Streight’s view along a neighboring ridge.

When Forrest’s 500 men appeared following the surrender, Streight angrily demanded he be allowed to renege on their surrender, but Forrest refused. Defeat proved especially bitter for the soldiers of the First Alabama Cavalry (USA), who had risked their families and homes to defend the Union despite their state’s decision to secede.

The Confederates transported Streight and the majority of his brigade to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. During the arduous trip, many of his weary malnourished soldiers succumbed to disease and many later died in prison, losing approximately 200 in total.

Streight’s Raid was an abysmal failure as a result of inadequate supplies, poor communication among Federal commanders, exaggerated estimates of Confederate forces and local Unionists, and bad luck. Streight was additionally hindered by locals throughout his march, while pursued by Forrest, who had the advantage of home territory and the sympathy and aid of the local populace.

In the end, the raiders failed to disrupt the Army of Tennessee’s supply lines and had no impact upon the battles fought in middle Tennessee and northwest Georgia during the summer and fall of 1863. In northern Alabama and northwest Georgia, accounts of Forrest’s heroics further elevated his already mythical status.

Equally important, the state of Alabama and the Confederacy acquired a wartime heroine, Emma Sansom, whose exploits would later reinforce postbellum notions that stressed the sacrifices and contributions of Confederate women during a war lost by southern men. The city of Gadsden erected a monument to Sansom in 1906.

On February 9, 1864, after nine months of incarceration, Abel Streight and 107 other soldiers escaped from prison by tunneling under their barracks, and was one of the 59 who eluded capture and made their way to freedom. Streight crossed through enemy territory and on his return gave a debriefing report to his Union commanders.

Eventually Streight was restored to active duty being placed in command of the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, IV Corps. He participated in the Battles of Franklin and Nashville in Tennessee. Streight was given a brevet promotion to brigadier general in the volunteer army dated March 13, 1865, and resigned from the army on March 16, 1865.

Image: General Abel Streight

Image: General Abel Streight

After the war, Streight immediately resumed his publishing business. In 1866, he and Lovina built a new home on Washington Street in Indianapolis, but by 1876 they also owned an estate on the National Road, two miles east of Indianapolis. He also established a lumber business, and had extensive land holdings.

In 1876, Streight ran succesfully for a seat in the Indiana state senate, serving a two year term. In 1880 he ran as the Republican candidate for Governor of Indiana, but was defeated. In 1888 he was once again elected as State Senator.

Abel Streight died in Indianapolis in 1892, and Lovina had her husband buried on the front lawn of their home. She reportedly stated on the day of the funeral: “I never knew where my husband was when he lived, so I buried him here. Now I know where he is.” She organized a yearly reunion of the Fifty-first regiment, and soldiers gathered at her home and encamped on her lawn during the State Fair.

Lovina also embraced spiritualism – the belief that spirits of the dead can communicate with the living. Anyone may receive spirit messages, but formal communication sessions (seances) are held by mediums. Spiritualism reached its peak growth in membership from the 1840s to the 1920s.

Lovina’s only child, John, died at about age fifty in 1905.

Lovina McCarthy Streight died on June 5, 1910, and was buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis with full military honors. Five thousand people attended her funeral, including sixty-four survivors of the Fifty-first Indiana Volunteers.

Abel Streight’s body was exhumed from the front lawn of the family home, and buried beside his wife. Lovina had purchased the plot in 1902, and commissioned Ralph Schway to sculpt a bronze bust of her husband for the memorial.

Lovina Streight’s will, filed in 1902, stipulated that her property and possessions be managed by public trustees for the purpose of establishing a home for elderly women.

Five of her relatives contested the will, stating that Lovina was not of sound mind when she signed the document. Friends of Lovina disagreed, and the case went to court in 1912. Evidence of Lovina’s eccentricities cited by her relatives included her practice of picnicking at her husband’s gravesite, wearing bright clothes and dancing with the neighborhood children. The jury agreed that Lovina was not of sound mind, and a judge declared the will invalid. Lovina’s heirs sold the home on December 30, 1915.

SOURCES

Streight’s Raid

Wikipedia: Abel Streight

1st Alabama Cavalry: Streight’s Raid