Author of the Most Famous Civil War Diary

Early Years

Early Years

Mary Boykin Miller was born on March 31, 1823, on her grandparents’ plantation near Stateburg, South Carolina, in the High Hills of Santee. Her grandfather, Burwell Boykin, served as an officer in the Revolutionary War under Francis Marion and established one of the largest upcountry plantations in the state. Her father, Stephen Decatur Miller, served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, and as governor of South Carolina.

Image: Mary Boykin Chesnut by Samuel Osgood, 1856

Mary grew up in the family’s modest country house in Stateburg called Plane Hill and attended school in Camden, South Carolina. When she was twelve years old, the family moved to Mississippi, but Mary stayed behind to continue her studies. She was enrolled in Madame Talvande’s French School for Young Ladies in Charleston, where she excelled in a course of study which stressed foreign language, history, rhetoric, literature and science – most unusual for the times.

She also acquired the grace and poise that made her popular at social gatherings, and the ideals that contributed to her intellectual independence. She formed lasting friendships with many other daughters of the planter elite, including her closest friend Mary Serena Chesnut Williams, a niece of James Chesnut, Jr.

James Chesnut, Jr.

James was born at Mulberry Plantation near Camden, South Carolina, January 18, 1815. The son of one of the state’s largest landholders, James had recently graduated from Princeton and was in Charleston studying law. He often dropped by to visit his niece at Madame Talvande’s and soon became enamored with classmate Mary Boykin Miller, who was only 13 years old.

Exaggerated rumors of Chesnut’s intentions prompted Stephen Miller to remove his daughter from the school in the fall of 1836 and bring her to Mississippi to join the rest of the family. The change from the cosmopolitan life of Charleston to the Mississippi frontier was drastic. Mary later viewed the Mississippi journey as an adventure that altered her attitudes toward Indians, slaves, and whites. She wrote in her diary that Mississippi was where, “I received…my first ideas that negroes were not a divine institution for our benefit—or we for theirs.”

Mary returned to Madame Talvande’s school in the fall of 1837, but following the death of her father in March 1838, she accompanied her mother back to Mississippi to settle financial affairs there. During the months required to reconcile the estate, James Chesnut wrote often and sent presents of books to help Mary pass the time.

Despite stiff competition from other suitors, Chesnut convinced Mary to marry him upon her return to South Carolina in March 1839. The wedding, however, was delayed indefinitely when James accompanied his older brother, John, to Europe to consult with physicians there about John’s failing health. The trip proved unsuccessful and John died in December 1839, leaving James the only surviving male heir to the Chesnut fortune.

Marriage and Family

On April 23, 1840, Mary Boykin Miller married James Chesnut, Jr., a member of another great plantation family. He was a lawyer and politician eight years her senior. The couple had no children, and were free to travel widely.

James Chesnut took his 17-year-old bride to live at Mulberry, the plantation home of the Chesnuts, located three miles south of Camden. Life at Mulberry was gracious, staid, and, from Mary’s point of view, tedious. The couple shared the large, Federal-style home with James’ parents, James Chesnut II and Mary Cox Chesnut, and his two sisters, Sarah and Emma, eleven and ten years her senior, respectively.

Accustomed since childhood to being the center of attention, Mary’s situation at Mulberry produced intense anxiety and frustration. She often felt inadequate and childish under what she perceived as the reproachful watch of her in-laws.

James Chesnut, Sr. was one of the wealthiest planters in the South, who owned 448 slaves and many large plantations. Despite the fact that James, Jr. was the only son, little of that property was in his name. Since his father only gave James a small allowance, he had to live mainly on his law practice.

Mary spent much of her time at Mulberry reading her way through the Chesnut library, one of the finest private collections in the South at that time. Her tastes in books ranged from the works of prominent European philosophers to what would have been considered by many of her contemporaries as decadent novels. Reading was her primary means of escape and sharpened her powers of observation.

Other activities included visiting or entertaining her many relatives in the area and helping Mary Cox Chesnut in small ways to manage the plantation staff. The stagnation of plantation life, however, took a toll on Mary’s psyche and may have contributed to her frequent bouts of illness.

In 1845, she became seriously ill with what she termed gastric fever, one of the recurring maladies that plagued her throughout her adult life. Concerned for her health, James decided to take Mary on a trip to the fashionable resorts of Saratoga and Newport in hopes that a change of scenery would lift her spirits and thereby improve her health.

Almost as soon as she and James had boarded the ship in Charleston for the voyage north, Mary began to show signs of recovering. She enjoyed the bustling activity of the northern cities, and after visiting for a month at the resorts, the couple decided to travel to Europe. Upon their return to Mulberry, Mary resolved to make such trips to the north as often as possible.

She and James also decided that they should have a home of their own closer to the Camden town center. In 1848, they moved into Frogden, a relatively modest wood frame house that still stands at 101 Union Street. Six years later, they built a larger and more elegant home called Kamschatka, after the remote Siberian peninsula by that name. It remains one of Camden’s finest antebellum residences.

James Chesnut in Politics

James’ political career began in 1840 when he was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives. He served four terms there, from 1840 to 1846 and from 1850 to 1852. In 1852, he was elected to the South Carolina Senate and served as its president from 1856 to 1858.

He gained a reputation as a solid, though an uninspiring orator and became an acknowledged leader of the conservative wing of the states’ rights movement. His popularity as a politician stemmed from his cool and reserved demeanor. His election to the U.S. Senate in 1858 was considered a victory for the moderates over the fire-eaters.

Mary actively participated in James’ career. She took pride in his position and helped with his correspondence and speeches, though she often disagreed with his conservative views. Her own political views, she admitted in a letter to James while he was serving as a South Carolina representative to the Nashville Convention to discuss the Wilmot Proviso of 1850, were “heterodox.”

Though a daughter of a framer of the positive good position on slavery and wife to the son of one of the largest slave owners in South Carolina, Mary was against slavery. She felt deep compassion for the plight of slaves, and believed that gradual emancipation was the correct solution to the problem.

At the same time, however, she was an avowed fire-eater on the question of states’ rights, despised northern abolitionists for their moral judgments against southern society and supported South Carolina’s secession from the Union.

After James’ election to the U.S. Senate in 1858, the Chesnuts sold Kamschatka and moved to Washington, DC. She naturally gravitated to a social circle that contained the wives of many of the South’s most influential politicians. Among her closest friends were the wives of Senators Louis T. Wigfall of Texas and Clement Clay of Alabama. She also formed a close relationship with Varina Davis, Jefferson Davis’ wife. Mary made regular appearances at balls, dinners, and teas and gained a reputation among both men and women as a charming hostess and excellent conversationalist.

Image: James and Mary Boykin Chesnut

Image: James and Mary Boykin Chesnut

As a young couple

The Civil War

Mary was on her way home from a two-week visit to her sister’s home in Florida in November 1860, when she learned that Abraham Lincoln had been elected president, and James had resigned from the U.S. Senate on November 10, 1860. Having grown accustomed to the excitement of Washington, DC, Mary had mixed feelings about leaving the city to return to South Carolina. Of James’ decision to resign Mary wrote, “I thought him right – but going back to Mulberry to live was indeed offering up my life on the altar of the country.”

James Chesnut was intimately involved in the formation of the Confederacy and served in a variety of high-level posts. Immediately after resigning from the Senate, he went to Columbia to assist in the organization of the South Carolina Secession Convention. He was a delegate to the convention when it convened in mid-December in Charleston, and served as a member of the committee charged with drafting the Ordinance of Secession. When the Confederacy formed a provisional Congress at Montgomery, Alabama, early the next year, Chesnut helped draft the nation’s permanent constitution.

Mary Boykin Chesnut’s Diary

The diary Mary Boykin Chesnut began in February 1861 was a way to record the events of her life during a period that she knew would alter the course of history. She was very politically aware, and analyzed the changing fortunes of the South through the war years. She also portrayed Southern society and the mixed roles of men and women.

In April 1861, during the siege of Fort Sumter, James Chesnut served as an aide to General P.G.T. Beauregard and rowed at night across Charleston Harbor to relay evacuation orders to Major Robert Anderson of the occupying Union force. After Anderson declined to surrender, Chesnut gave orders to nearby Fort Johnson to open fire on Fort Sumter, and the first shots of the Civil War were fired, on April 12, 1861. Mary’s diary tells of her excitement at sitting on the roof of a house in Charleston watching the bombardment of Fort Sumter.

In the summer of 1861 Chesnut also took part in the Battle of First Bull Run as an aide-de-camp to Beauregard. He then served a similar position for CSA President Jefferson Davis’ staff.

Mary accompanied James to his various posts throughout the war, acted as his administrative aide, and hosted or attended an endless round of social gatherings. Mary also made frequent trips to relatives and friends, sewed shirts for soldiers and sewed sandbags for coastal defense, and raised supplies for Richmond hospitals.

During the war, Mary came in contact with nearly all of the Confederacy’s most influential leaders. Charming, outgoing, intelligent, and inquisitive, she had a unique ability to extract first-hand, often sensitive, information from a litany of political and military leaders that she came into contact with on an almost daily basis through the many social gatherings she hosted or attended.

In her diary, Mary wrote historically valuable portraits of close friends such as Jefferson and Varina Davis, the Lees, Louis T. Wigfall, C. Clement Clay, the Prestons, Stephen R. Mallory, Robert M.T. Hunter, and Generals John Bell Hood, Wade Hampton and Joseph E. Johnston. She described people in penetrating and enlivening terms, and captured the growing difficulties of all classes in the Confederacy.

Throughout the war, Mulberry was Mary’s primary residence, though James’ duties required extended trips to Richmond and Columbia. While it was relatively isolated in thousands of acres of plantation and woodland, they entertained many visitors.

The following passage is one of her most vivid descriptions of Mulberry and her life there during the early years of the conflict:

My sleeping apartment is large and airy–has windows opening on the lawn east and south; in those deep window seats, idly looking out, I spend much time. A part of the yard which was a deer park once has the appearance of the primeval forest–the forest trees having been unmolested… are now of immense size.

In the spring the air is laden with opopanaz, violets, jasmine, crab apple blossoms, roses. Araby the blest never was sweeter perfume. And yet there hangs here as in every Southern landscape the saddest pall. There are browsing on the lawn, when Kentucky bluegrass flourishing, Devon cows and sheep, horses, mares and colts. It helps to enliven it.

Then carriages are coming up to the door and driving away incessantly…I take this somnolent life coolly. I could sleep upon bare boards if I could once more be amidst the stir and excitement of a live world. These people have grown accustom to dullness. They were born and bred in it. They like it as well as anything else.

In 1864 James Chesnut received a commission as a brigadier general and commanded the South Carolina reserves until the end of the war. He was assigned to the relative safety of Chester, South Carolina, and Mary joined him there.

The End is Near

In the fall of 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman began his famous March to the Sea. After Sherman made Georgia “howl”, he plowed his way through the heart of South Carolina. He was met with little resistance. Mary Chesnut wrote of the fear he and his troops struck in their hearts. By this time Confederate money was worth next to nothing. Mary was forced to sell her old clothes to buy food for survival.

Near the end of the war, Mary began to view Mulberry in a different light. The place and its occupants symbolized the gentile society of the old guard planter elite, which she often criticized but could not help but feel nostalgia for on the eve of its demise. Leaving Mulberry in December 1864, she wrote, “Took a last fond farewell of Mulberry – once so hated, now so beloved.”

Mary was at Chester when the news of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox arrived. As had been commonplace throughout the war, a number of prominent people in the Confederate hierarchy – including John Bell Hood, Clement Clay, and Varina Davis and her children – came to the Chester house, for discussion and comfort.

“Night and day,” she wrote, “this landing and these steps are crowded with the Elite of the Confederacy – going and coming – and when night comes… more beds are made on the floor of the landing place… The whole house is a bivouac.”

After the war ended, Mary and James returned to Mulberry, which had been damaged by a Union raiding party. War had ravaged their holdings and freed their slaves. A diary entry for the first week of May 1865 reads, “In crossing the Wateree [River] at Chesnut’s Ferry, we had not a cent to pay the ferry man – silver being required.”

The Chesnuts went from great prosperity to desolation in the short span of five years. James’ father died at the age of 90 in 1866, leaving Mulberry and extensive debts to James, who spent his time trying to get the plantation back in order and again assumed a prominent role in local and state politics.

Though bitterly upset by the shattered society around her and often suffering bouts of depression and illness, Mary ran the household and started a small dairy business with an outlet in Charleston that for some time was the only family income. Mary wrote: “The first solid half dollar [we earned was] for butter… John C. and my husband laughed at my peddling – and borrowed the money.”

James worried about Mary’s future. Should he die before her, she would be left with nothing; Mulberry would belong to the direct Chesnut descendants. So in 1872, James and Mary began building a simpler home in Camden, which they named Sarsfield. Because materials were expensive and scarce, James had the separate kitchen building behind Mulberry razed, and the bricks used to erect the new house. The house was built with considerable input from Mary, and featured a comfortable library with a bay window that overlooked the grounds, which was originally more than 50 acres.

Paring Down the Diary

In the early 1870s while still living at Mulberry, Mary began to think seriously about revising her diary for publication. After moving to Sarsfield, she began writing in earnest, but switched her attention from the diary to writing fiction. She wrote two novels simultaneously during the years between 1872 and 1876. One was autobiographical, centering on her experiences in Mississippi, and named Two Years of My Life. The other was a war novel called The Captain and the Colonel.

Realizing that the material she collected during the Civil War offered a much more interesting story than the fiction she was attempting to write, Chesnut abandoned the novels in 1875 and began the arduous process of paring down the diary, which in its raw form filled numerous notebooks of varying size and amounted to more than 400,000 words.

Mary Chesnut kept the diary of her wartime experiences between February 18, 1861 and June 26, 1865. With the exception of a very hectic period in 1863 and early 1864, she was faithful to her resolution to keep a record of the times. Seven volumes of her original journal survive, though it is known that at least five additional volumes existed. The passages in them are often cryptic references to people and events, written hastily between social gatherings, frequent trips, and bouts of illness.

In its original form, the diary was an uneven, sometimes cryptic, collection of passages written in a free-flowing stream of consciousness during brief lulls in an extremely hectic schedule. Kept under lock and key, it contained Mary’s most private thoughts and was clearly intended for her eyes only. It was peppered with frank, often critical remarks about Southern leaders, people within her social circle, and even her friends and family.

By the spring of 1876, Mary had made the initial edit of the years between 1861 and 1864, and then abruptly stopped work. Despite her efforts to be succinct, her first version of the revised diary would have amounted to well over two thousand pages. It is possible that she stopped work on the diary because she felt that the material was still too controversial to publish.

The sensitivity of some issues Mary addressed in her diary – her opposition to slavery and her ideas about the place of women in a male dominated society – could be considered heretical. She was forthright about complex situations related to slavery, particularly the problem of white men fathering children with enslaved women in their own extended households. Such revelations, should they have become public during the Civil War or its immediate aftermath, would have caused great harm to her social standing.

Failing Health

By 1880 Mary began to have problems with her lungs and heart, and at times was forced to stop editing her diary. She also watched her mother and James fall into bad health in the early part of the decade.

In the early 1880s, despite failing health that often confined her to her bed, Mary resumed the process of editing her diary. It is not known exactly how many of the original journals she had in front of her when she compiled the work that ultimately was published as her diary. Portions of the original journal that survive today span from February 18, 1861 through December 8, 1861, January through February 1865, and May 7 through June of 1865.

There were undoubtably other volumes, though there were probably several extended periods during the busy years of 1863 and 1864 where she made few, if any, entries. To fill those gaps when revising her journal, she used newspaper clippings, correspondence that she had saved, and her memory to recreate events and conversations.

Her intention was to eliminate all of what she deemed trivial and personal and to provide a solid historical accounting of her experiences. She took many liberties with the original material, sometimes omitting important elements and substituting new passages in their place. Events that occupied two sentences in the original journal were often expanded to occupy several pages of text.

James Chesnut died in February 1885. Their relationship, which Mary admitted in her journal had been strained at times, had, through many shared experiences of happiness and tragedy, grown into one of deep mutual understanding and love.

After James’ death, Mary was left with a struggling dairy farm and a strong desire to complete her memoirs. Grief stricken, she became intensely depressed, and fell ill again. She found life extremely difficult without her husband’s companionship. She lived the last twenty months of her life at Sarsfield; her annual income was a paltry sum of 100 dollars.

She managed to find the strength, however, to continue writing. In the end, she condensed her diary down from 400,000 words to 150,000 words, deleting the more personal passages. She realized her records would “at some future day afford facts about these times and prove useful to more important people than I.”

Though the final version was much more polished and showed Mary’s desire to create a readable piece of literature, the basic form of the book followed that of the original diary. Conscious from the start of the historical importance of the moment, she took pains to paint a complete and accurate picture of the rise and fall of the Confederacy.

Through her travels and a certain amount of luck, she was an eyewitness to many important events during the war. As she put it in her diary in the latter stages of the war, “It was a way I had, always to stumble in upon the real show.”

The resulting work is an understated masterpiece of Southern literature. The practice that she had in her earlier attempts at fiction served her well when rewriting the journal. She had become accomplished at characterization and dialogue, and used several different narration techniques, alternating between the first and third persons. Literary scholars have called the Chesnut diary the most important work by a Confederate author.

Mary Boykin Chesnut died of a heart attack at Sarsfield on November 22, 1886, at the age of 63. Mary and James are buried side by side in the Chesnut family plot at Knights Hill Cemetery in Camden.

Some months before her death, Mary gave her diary to her closest friend, Isabella D. Martin, and urged her to have it published. It was not until nearly 20 years later, however, that a New York journalist, Myrta Lockett Avary, stumbled upon the work and convinced Martin to co-edit and publish it.

Well-Earned Recognition

Mary Chesnut’s writing was finally published in 1905 as A Diary from Dixie, edited by Isabella D. Martin and Myrta Lockett Avary. Though the editing was sloppy and heavy-handed, the genius of Chesnut’s writing shone through, and the work was a popular success.

In 1949, another version edited by novelist Ben Ames Williams, also named A Diary from Dixie, was published. Though it included more material than the previous publication and was annotated to identify the people and places, it fell far short of conveying the full breadth and import of Chesnut’s work.

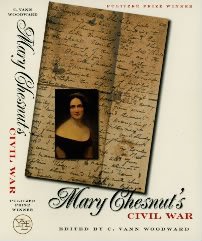

The 1981 version of the diary, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, was edited by prominent historian C. Vann Woodward and is considered the most reliable edition. This edition combines the diary and the memoir – what Mary actually recorded during the war and what she wrote twenty years later. It won the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1982.

The 1981 version of the diary, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, was edited by prominent historian C. Vann Woodward and is considered the most reliable edition. This edition combines the diary and the memoir – what Mary actually recorded during the war and what she wrote twenty years later. It won the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1982.

Woodward summed up the significance of the diary in the following passage:

The importance of Mary Chesnut’s work…lies not in autobiography, fortuitous self-revelations, or opportunities for editorial detective work. She is remembered only for the vivid picture she left of a society in the throes of its life-and-death struggle, its moment of high drama in world history…The enduring value of the work, crude and unfinished as it is, lies in the life and reality with which it endows people and events and with which it evokes the chaos and complexity of a society at war. Her cast of characters includes slaves and brown half brothers, poor whites and sandhillers, overseers and drivers, common soldiers and solid yeomen, as well as the very top elite of state, military, and society that thronged her drawing room and saw her daily. She brings to life the historic crisis of her age with the literary techniques she learned in the meantime…

In 1984, Woodward and Elisabeth Muhlenfeld published the original journals on which the larger work was based as The Private Mary Chesnut: The Original Civil War Journals.

When the National Portrait Gallery devoted a gallery to the Civil War in the mid-1980s, Mary Boykin Chesnut held center stage – the only woman in the room – surrounded by Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. In a very flattering portrait by Samuel Osgood, Chesnut stood alone among all those powerful men.

In 1990, Ken Burns used extensive readings from Chesnut’s diary in his award-winning documentary television series, The Civil War. Academy Award-nominated actress Julie Harris read these sections.

In 2000, Mulberry Plantation was designated a National Historic Landmark, the highest honor for a site, due to its importance to America’s national heritage and literature. The plantation was where Mary Boykin Chesnut resided when she wrote most of her diary. The plantation and its buildings are representative of James and Mary Chesnut’s elite social and political class.

The U.S. Post Office honored her with a stamp in their Civil War series, along with only two other women, nurses Clara Barton and Phoebe Pember. In 2001, CSPAN’s American Writers Series included four writers to represent the Civil War era: Abraham Lincoln, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Frederick Douglass and Mary Chesnut.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Mary Boykin Chesnut

The Heath Anthology of American Literature

New World Encyclopedia: Mary Boykin Chesnut

Mary Boykin Chesnut Writes Between the Lines, by Elisabeth Showalter Muhlenfeld

AUTHOR’S NOTE: My maiden name is Boykin, and I was born in North Carolina. When I did some rudimentary research about my family’s history several years ago, I recall seeing the name Burwell Boykin, who was Mary Boykin Chesnut’s grandfather. If I didn’t insist on writing all these blogs :), I might have time to find out more about my ancestors.

My maternal great-grandmother was born a Boykin, Emma Louise Boykin, from Mobile, she moved with her husband Antoine Frank my great grandfather to east Texas after the Civil War. She has descendants my siblings and cousins in Texas and other states. I landed in Smithfield VA in recent years and discovered Boykin was a prominent 18th and 19th century name here, a couple local landmarks from the Revolution and Civil War carry the name. Does any of this sound familiar?