Wife of Union General George Thomas

Frances Lucretia Kellogg was born at Troy, New York, on January 25, 1821. Frances’ mother, Abigail Paine Kellogg, had been a widow for many years. Her father Warren Kellogg was a prosperous hardware and grocery merchant.

Frances Lucretia Kellogg was born at Troy, New York, on January 25, 1821. Frances’ mother, Abigail Paine Kellogg, had been a widow for many years. Her father Warren Kellogg was a prosperous hardware and grocery merchant.

Image: General George Thomas

George Henry Thomas was born July 31, 1816, on a farm called Thomaston in Southampton County, Virginia, five miles from the North Carolina line. He was one of nine children born to John and Elizabeth Rochelle Thomas. There were six girls and three boys; George was the youngest son.

The family led an upper-class plantation lifestyle. By 1829, they owned 685 acres and 24 slaves. John Thomas died in a farm accident April 20, 1829, leaving the family in financial difficulties. George, his sisters and his widowed mother were forced to flee from their home and hide in the nearby woods during Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion.

Thomas lived at Thomaston until his appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1836, where he roomed his first year with future Civil War general, William Tecumseh Sherman. Entering at age 20, Thomas was known to his fellow cadets as “Old Tom.” He was appointed a cadet officer in his second year, and graduated 12th in a class of 42 in 1840.

After graduation, Thomas was appointed a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery, and he fought in the Seminole Wars in Florida. From 1842 until 1845, Thomas served in posts at New Orleans, Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor, and Fort McHenry in Baltimore.

With the Mexican-American War looming, his regiment was ordered to Texas in June 1845. In Mexico, Thomas led a gun crew with distinction at the battles of Fort Brown, Resaca de la Palma, Monterrey, and Buena Vista, receiving three brevet promotions. During the war, Thomas served closely with an artillery officer who would be a principal antagonist in the Civil War – Captain Braxton Bragg.

Thomas was reassigned to Florida in 1849. In 1851, he returned to West Point as a cavalry and artillery instructor, where he established a close professional and personal relationship with another Virginia officer, Robert E. Lee, the Academy superintendent. Thomas’ appointment there was based in part on a recommendation from Braxton Bragg.

Among his fellow students were future Civil War generals Philip Sheridan, J.E.B. Stuart and Fitzhugh Lee. Thomas recommended Stuart and Lee for assignment to the cavalry, and they later became prominent Confederate cavalry generals.

On November 17, 1852, Thomas married Frances Kellogg at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Troy, New York. The church register indicates that the official witnesses were her brother John F. Kellogg and her uncle Daniel Southwick. George was 36 years old; Frances was 31. The couple had a happy marriage, but no children. The couple remained at West Point until 1854.

Thomas was promoted to captain on December 24, 1853. In the spring of 1854, his artillery regiment was transferred to California, and he led two companies to San Francisco via the Isthmus of Panama, and then on a grueling overland march to Fort Yuma, Arizona.

On May 12, 1855, Thomas was appointed a major of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry by Jefferson Davis, who was then the Secretary of War. Thomas resumed his close ties with the second-in-command of the regiment, Robert E. Lee, and the two officers traveled extensively together on detached service for court-martial duty.

In October 1857, Major Thomas assumed acting command of the cavalry regiment, an assignment he would retain for 2½ years. On August 26, 1860, during a clash with a Comanche warrior in Texas, Thomas was wounded by an arrow passing through the flesh near his chin area and sticking into his chest. Thomas pulled the arrow out and, after a surgeon dressed the wound, continued to lead the expedition. This was the only combat wound that Thomas suffered throughout his long military career.

In November 1860, Thomas requested a one-year leave of absence. On his way home to North Carolina, he suffered a mishap in Lynchburg, Virginia, falling from a train platform and severely injuring his back. This accident led him to contemplate leaving military service and caused him pain for the rest of his life. Continuing to New York to visit his wife’s family, Thomas stopped in Washington, DC, and conferred with general-in-chief Winfield Scott.

When the secession crisis began, Thomas was still on furlough, recovering from his back injury. Thinking that he was too badly injured to return to active service, he applied for a position as instructor at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington in January 1861.

In March, he turned down an unsolicited offer to serve in the Virginia state militia, and when he was called back to active service after the surrender of Fort Sumter at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, on April 14, he immediately reported for duty.

Thomas in the Civil War

When the Civil War began, many Southern-born officers were torn between loyalty to their states and loyalty to their country. Nineteen officers in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry resigned, including three of Thomas’ superiors – Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee and William Hardee.

Thomas struggled with the decision but ultimately remained in the U.S. Army. After the war, he explained that he felt his oath as an army officer to uphold the United States Constitution and to protect the national government left him no other choice. His Northern-born wife and his dislike of slavery probably influenced his decision.

His loyalty to the United States angered his sisters, who continued to live at Thomaston. They allegedly refused to send him the sword that the county had presented to him for his Mexican War service. They turned his picture to the wall and destroyed his letters. While he later reconciled with his brothers, his sisters remained estranged from him until his death.

Nevertheless, Thomas stayed in the Union Army with some degree of suspicion surrounding him. His antebellum career had been distinguished and productive, and he was one of the rare officers with field experience in all three combat arms – infantry, cavalry, and artillery.

Thomas was promoted in rapid succession, to lieutenant colonel on April 25, 1861, (replacing Robert E. Lee), and to colonel on May 3, (replacing Albert Sidney Johnston) in the regular army, and brigadier general of volunteers on August 17, 1861.

During the First Manassas Campaign (1861), Thomas served as the head of cavalry for a force that invaded Virginia (now West Virginia) near Martinsburg, but all of his subsequent assignments were in the Western Theater.

In August 1861, Thomas was transferred to Kentucky, where he took charge of a camp of Union recruits south of Frankfort. On January 19, 1862, his force of slightly over 4000 men decisively defeated a Confederate force of equal size at the Battle of Mill Springs. This victory secured eastern Kentucky for the Union and brought Thomas to national attention.

After Mill Springs, General Thomas commanded the 1st Division of Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio.

The victor at Shiloh, General Ulysses S. Grant, came under severe criticism for the bloody battle and his superior, Major General Henry Halleck, reorganized his Department of the Mississippi to ease Grant out of direct field command.

The three armies in the department were divided and recombined into three “wings.” Thomas, promoted to major general effective April 25, 1862, was given command of the Right Wing, consisting of four divisions from Grant’s former Army of the Tennessee and one from the Army of the Ohio. Thomas successfully led this army in the Siege of Corinth (May 1862).

On June 10, Grant returned to command the original Army of the Tennessee. Thomas resumed service under Don Carlos Buell. Thomas served as Buell’s second-in-command at the Battle of Perryville on October 8, 1862; although tactically inconclusive, the battle halted CSA General Braxton Bragg’s invasion of Kentucky as he voluntarily withdrew to Tennessee.

Frustrated with Buell’s cautious tendencies and ineffective pursuit of Bragg, President Abraham Lincoln offered command of the Army of the Ohio to Thomas, who refused, stating that he did not want others to think he had schemed against his superior officer. The Union high command then put Major General William Rosecrans in charge.

Thomas at Chickamauga and Chattanooga

Fighting under Rosecrans, commanding the “Center” wing of the newly renamed Army of the Cumberland – the main Union force in Tennessee – Thomas gave an impressive performance at the Battle of Stones River (December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863). He held the center of the retreating Union line and once again preventing a victory by Bragg.

Thomas was in charge of the most important part of the maneuvering from Decherd to Chattanooga, Tennessee during the Tullahoma Campaign (June 22 – July 3, 1863) and the crossing of the Tennessee River.

General Thomas’ most important test came during the Battle of Chickamauga (September 19–20, 1863). Commanding the XIV Corps, Thomas occupied the northern flank of the Union line, and received the brunt of the Confederate attacks on the first day of that battle. Throughout the day, Thomas skillfully maintained a defensive line and counterattacked to recover lost ground.

On the second day of the battle, a series of errors and miscommunications between Rosecrans and his subordinates left a gap in the center of the Union line. CSA General James Longstreet, commanding a Confederate corps sent to Tennessee from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, launched an attack directly into the gap.

Longstreet’s men poured through the hole in the lines and spread out, attacking the Union forces in the flank and rear. Most of the Union army fled the field, along with Rosecrans and two of the army’s corps commanders. By noon, Thomas’ corps was the only organized force still on the field.

Thomas improvised a defensive line and held off repeated attacks from a numerically superior opponent. He led several counterattacks in person, at great risk, and his stand held the Confederate army at bay until nightfall, preventing them from pursuing and destroying the rest of the Union army. Lincoln remarked that “it is doubtful whether his heroism and skill … has ever been surpassed in this world,” and earned Thomas the name, the Rock of Chickamauga.

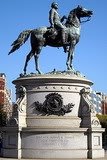

Image: The Rock of Chickamauga

Image: The Rock of Chickamauga

After Chickamauga, Thomas succeeded Rosecrans in command of the Army of the Cumberland. He was still subordinate to Ulysses S. Grant, whom Lincoln had appointed to run the war in the West. Thomas served effectively as Grant’s subordinate during the Battle of Chattanooga (November 23–25, 1863), where his men spontaneously charged the Confederate lines atop Missionary Ridge and sent the Confederates into retreat.

Thomas at Atlanta and Nashville

General Thomas served under General William Tecumseh Sherman during the Atlanta Campaign (spring 1864) and fought in a number of engagements, including Kennesaw Mountain. At the Battle of Peachree Creek (July 20, 1864), Thomas’ defense severely damaged CSA Major General John Bell Hood‘s Army of Tennessee in its first attempt to break the siege of Atlanta.

After the capture of Atlanta, Sherman took most of the Union army on his March to the Sea through Georgia, leaving Thomas with a mix of veteran and garrison troops to defend Tennessee. General Hood decided not to follow Sherman south, instead turning north and invading Tennessee. Sherman ordered George Thomas north to Nashville, where he was to block General Hood from advancing.

At the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, on November 30, 1864, a large part of General Thomas’ force, under command of Major General John Schofield, dealt Hood a strong defeat and held him in check long enough to cover the concentration of Union forces in Nashville.

At Nashville, Thomas had to organize his forces, which had been drawn from all parts of the West, including many young troops. He declined to attack until his army was ready and the ice covering the ground had melted enough for his men to move. General Grant (now general-in-chief of all Union armies), grew impatient at the delay. Major General John Logan was sent with an order to replace Thomas, and soon afterwards Grant left Virginia to take command in person.

Thomas concentrated his forces at Nashville and attacked Hood outside the city, and in the two-day Battle of Nashville (December 15–16, 1864) crushed Hood’s army. This left Tennessee in secure Union control and rendered Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia vulnerable to Union raids.

General Thomas sent his wife Frances the following telegram, the only communication surviving of the Thomases’ correspondence: “We have whipped the enemy, taken many prisoners and considerable artillery.”

After ordering Thomas, “Delay no longer for weather or reinforcements,” on December 11, 1864, Grant received word of the Battle of Nashville on December 16, with Thomas’ aide telling the general-in-chief of the rout of Hood’s Army. Grant stated in a note to Thomas on the 16th, “I was just on my way to Nashville, but receiving a dispatch from Van Duzer detailing your splendid success of to-day, I shall go no further.”

Thomas was appointed a major general in the regular army, with date of rank of his Nashville victory, and received the Thanks of Congress:

… to Major-General George H. Thomas and the officers and soldiers under his command for their skill and dauntless courage, by which the rebel army under General Hood was signally defeated and driven from the state of Tennessee.

Thomas had commanded African American troops during the Battle of Nashville, and their bravery permanently changed his views on race. He had been a racial conservative during most of the war, but he changed after Nashville and became a staunch supporter of the rights of freedmen.

After the War

From 1865 to 1869, General Thomas commanded the Union forces in the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky and Tennessee, and at times his district also included Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and West Virginia.

During Reconstruction, Thomas acted to protect freedmen from white abuses. He set up military commissions to enforce labor contracts since the local courts had either ceased to operate or were biased against blacks. When local courts refused to prosecute whites for attacking blacks, Thomas tried them in military tribunals.Thomas also used troops to protect places threatened by violence from the Ku Klux Klan.

President Andrew Johnson offered Thomas the rank of Lieutenant General – with the intent to eventually replace Grant, a Republican and future president, with Thomas as general in chief – but the ever-loyal Thomas asked the Senate to withdraw his name for that nomination because he did not want to be party to politics.

In 1869, General Thomas requested assignment to command the Division of the Pacific with headquarters at the Presidio at San Francisco, California.

Major General George H. Thomas died of a stroke on March 28, 1870, at the Presidio, at the age of 54. He died while writing an answer to an article written by his wartime rival, Union General John Schofield, in which he criticized Thomas’ military career.

He was the first high-ranking Union general to die after the Civil War, and his coffin was greeted by crowds throughout its transfer back East. President Ulysses S. Grant, General William Tecumseh Sherman, and many senior government officials attended a large public funeral at Thomas’ wife’s church in Troy, New York.

Both Sherman and Grant were reported by third parties to have been visibly moved by his passing. Thomas’ legendary bay horse, Billy, bore his friend Sherman’s name. General Thomas was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Troy. None of his blood relatives attended the funeral.

Frances Lucretia Kellogg Thomas died at Washington, DC, on December 26, 1889.

Legacy

Thomas has generally been held in high esteem by Civil War historians; Bruce Catton and Carl Sandburg wrote glowingly of him. Many consider Thomas one of the top three Union generals of the war, after Grant and Sherman, but Thomas never entered the popular consciousness like those men.

The Army of the Cumberland veterans’ organization, throughout its existence, fought to see that he was honored for all he had done. Thomas destroyed his private papers before he died, saying he did not want “his life hawked in print for the eyes of the curious.”

Image: General George Thomas Monument

Image: General George Thomas Monument

The statue erected in Thomas Circle in Washington, DC, in 1879. Thomas’ sisters, eventually more sorry than angry, supported the statue. Inscription: Erected by his Comrades of the Society of The Army of the Cumberland

In 1877, General Sherman published an article praising Thomas:

During the whole war his services were transcendent, winning the first substantial victory at Mill Springs in Kentucky, January 20th, 1862, participating in all the campaigns of the West in 1862-3-4, and finally, December 16th, 1864, annihilating the army of Hood, which in mid-winter had advanced to Nashville to besiege him.

In 1999 a statue of Thomas by sculptor Rudy Ayoroa was unveiled in Lebanon, Kentucky.

SOURCES

About North Georgia

Catching Up With “Old Slow Trot”

Wikipedia: George Henry Thomas

The George H. Thomas Home Page

Encyclopedia Virginia: George H. Thomas

The Historical Marker Database: Thomaston

St. Paul’s in Troy is still a working church, holding services every week.