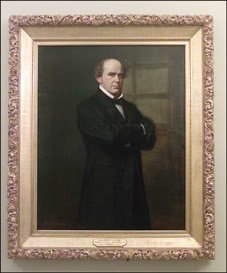

Wife of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Salmon P. Chase

And husband of Eliza Chase

Henry Ulke, Artist

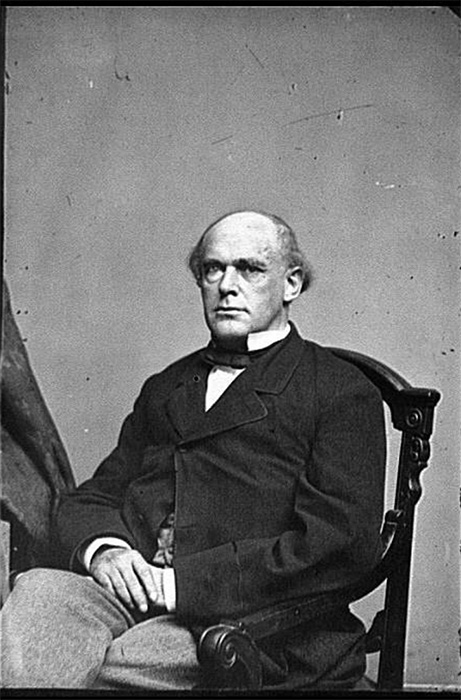

Salmon Portland Chase was born on January 13, 1808, in Cornish, New Hampshire. He was the ninth of eleven children born to Ithmar Chase and Janet Ralston Chase. His father died when Salmon was nine years old, leaving his widow a small amount of property and ten surviving children. Chase’s education began in 1816 in Keene, New Hampshire, than at a better school in Windsor, Vermont.

His uncle, Philander Chase, an Episcopal Bishop, took Salmon to the woods of Ohio. Young Chase attended the bishop’s school at Worthington, near Columbus. Chase had no love for the monotonous life of farm work. His uncle worked him hard while he simultaneously studied Greek for two years.

In 1822, Cincinnati College appointed Bishop Chase president of the college. At fifteen years old, Salmon Chase was admitted as a sophomore. The Bishop only served there a year, then traveled to Great Britain to raise money for the founding of the Theological Seminary in Ohio, later to be called Kenyon College.

When his uncle left his position as president the following year to travel to England, Salmon Chase returned to New Hampshire, and enrolled at Dartmouth College as a junior, graduating with honors in 1826.

After graduation, Chase moved to Washington, DC, where he taught school while studying law under William Wirt, who was United States Attorney General in the administration of John Quincy Adams. Although he wanted to practice law in Washington, Chase did not meet the residency requirement.

Ohio allowed him to use the time he had lived there with his uncle; after he passed the bar in 1829, he moved to Cincinnati to set up his law practice. As a young lawyer, Chase consolidated Ohio’s statutes into a three-volume reference work. This important contribution to Ohio’s legal literature helped improve his professional reputation.

Marriage and Family

Chase married Catherine Jane Garniss on March 4, 1834. She died the following year while giving birth to the couple’s first child, a girl who died a few years later.

Chase married Eliza Ann Smith on September 26, 1839. Eliza gave birth to Kate (Katherine Jane) Chase on August 13, 1840, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Eliza Chase died of consumption shortly after Kate’s fifth birthday. Consumption, known today as tuberculosis, was a common disease with no cure.

On November 6, 1846, Chase married Sarah Bella Dunlop Ludlow, with whom Kate Chase had a difficult relationship. After Sarah’s death, also of consumption, on January 13, 1852, Chase did not remarry. Widowed three times and haunted by the deaths of four children, Salmon Chase cherished his two surviving daughters – Kate and her younger sister Nettie, who both survived their father.

Kate Chase grew into a beautiful and smart young woman, who was the apple of her father’s eye. She is best known as a society hostess during the Civil War, and a strong supporter of her father’s political ambitions.

The effects of death, always so near, deepened Salmon Chase’s religious fervor. Days spent in Bible reading and prayer, and soul torture for possible neglect of duty in not impressing others with the need of salvation, left a deep mark on Chase.

Chase as a Young Lawyer

As a practicing attorney, Chase made his permanent home in Cincinnati. It was a wise choice. Located on the north bank of the Ohio River, with its busy western trade and with slave territory on the opposite bank, Cincinnati offered splendid opportunities for a young lawyer of ability and strong moral views.

Chase became convinced that slavery was a sin and that African Americans deserved not only freedom but also civil rights. He took part in the antislavery movement and other reform activities. Chase’s legal talents were quickly recognized. He defended a number of escaped slaves in local as well as federal courts, including the Supreme Court, and he was soon being called the attorney for runaway slaves. In 1834, Chase defended abolitionist editor and activist James Birney, who had been arrested for helping a runaway slave to escape.

His most famous case was the defense of John Van Zandt, who had been arrested while carrying a number of Kentucky runaway slaves to freedom under a load of hay in 1842. Chase and William H. Seward, acting as unpaid lawyers, carried Vanzant’s case to the U.S. Supreme Court, where their eloquent appeals for minority rights on constitutional grounds attracted national attention.

Chase’s insistence that no claim to persons as property could be supported by any United States law won antislavery support among those who rejected William Lloyd Garrison’s extreme militant views. It also served to advance Chase’s political standing in Ohio and led to correspondence with such national antislavery figures as Charles Sumner.

Chase in Politics

Initially a Whig, Chase helped form the antislavery Liberty Party, and became one of its leaders, and of the Free-Soil Party in Ohio in 1848, which was dedicated to the non-expansion of slavery. A coalition of Free Soilers and Democrats in Ohio elected Chase to the United States Senate in early 1849.

During his single term, Chase vehemently condemned the Fugitive Slave Law, and used his position to protest measures such as the Compromise of 1850. His Appeal of the Independent Democrats was a classic expression of protest against a conspiracy to nationalize slavery.

Chase’s opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 provoked him to help organize the Anti-Nebraska Party in Ohio, which soon became known as the Republican Party.

In 1855, Chase successfully ran for governor of Ohio as a Republican. Slavery was the dominant issue of the campaign. As governor he advocated public education and prison reform. He also supported reform of the state militia and improved property rights for women. Chase was re-elected as governor in 1857, but his second term was much less productive as Democrats gained control of the state legislature.

Chase’s ultimate political goal was to become President of the United States, but he failed to gain the Republican nomination in 1856. The principal reason for these losses was his radical abolitionist views.

In the meantime, Republicans regained control of the Ohio legislature in 1859 and sent Chase back to the Senate. His chances for the Republican nomination for president in 1860 seemed promising. But at the Republican convention, the Ohio delegation was divided, and on the third ballot, transferred four votes to Abraham Lincoln, which gave him the necessary majority, placing Chase in a favorable position for a cabinet post if Lincoln was elected.

Chase as Secretary of the Treasury

Only two days after taking his seat in the Senate, Salmon Chase resigned to become Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury. Chase had an immediate challenge: the American Civil War began, and it was his job to find a way to finance the Union war effort. Vast sums of money had to be borrowed, bonds marketed, and the national currency kept as stable as possible.

With customs revenue from the Southern cotton trade cut off, Chase had to implement internal taxes. The Bureau of Internal Revenue, later the Internal Revenue Service, was created in 1862 to collect stamp taxes and internal duties. The next year, it administered the nation’s first income tax.

Interest rates soared, and soon a resort to paper currency was reluctantly accepted. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing was established in 1862 to print the government’s first currency, known as greenbacks because of their color. Chase disapproved of them in principle – these were legal tender notes not backed by specie, and could be printed in unlimited quantities and were therefore inflationary.

During Chase’s years as secretary of the treasury, the United States began to print “In God We Trust” on all currency. Chase earned the nickname Old Mister Greenbacks, after placing his own face on the front of the one-dollar bill. His motive was to make sure that Americans knew who he was.

He was instrumental in establishing the National Banking System in 1863, which opened a market for bonds and stabilized currency. The greenbacks, within a new network of national banks, directly involved the government in banking for the first time.

The Emancipation Proclamation

In his diary, Secretary Chase recorded the cabinet meeting on September 22, 1862, where the draft Emancipation Proclamation was approved: “To Department about nine. State Department messenger came, with notice to Heads of Departments to meet at 12.—Received sundry callers.—Went to White House.”

After reading a second draft to the Cabinet, Lincoln issued his preliminary Proclamation, which announced that emancipation would become effective on January 1, 1863, in those states ‘in rebellion’ that had not, during the interim period, ceased hostilities. He issued and signed the supplementary or real Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. It says, in part:

Whereas, on the September 22, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

Chase was often critical of the president, whom he viewed as incompetent and confused. His main complaints were against keeping General George B. McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac and the refusal to use Negro troops. Chase’s radical antislavery views, as well as his political ambitions, put him at odds with the more moderate Lincoln.

Chase’s constant disagreement with administration policies gained him a following among the Radical Republicans in Congress. Chase was a bureaucratic meddler whose interests ranged well beyond the Treasury Department. He often involved himself in policy regarding the army and allied himself with the Radicals, while using Treasury agents to set up a political network around the country.

After the terrible Union loss at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, a group of senators, influenced by Chase’s complaints, held a secret caucus and drew up a document to be presented to the President, demanding “a change in and a partial reconstruction of the Cabinet.” It was, in fact, an effort to remove Seward and to advance Chase. On learning of the plan, Seward sent his resignation to the President, who put it aside.

Then, by bringing the protesters and the rest of the Cabinet together for a frank discussion, Lincoln skillfully led Chase to repudiate some of his charges. This hurt Chase with both friend and foe. The next morning he offered his own resignation. Lincoln now held both Seward’s and Chase’s resignations and, having gained the upper hand, refused to accept either.

A Chase associate, Hugh McCulloch, later wrote that “personal relations between Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Chase were never cordial. They were about as unlike in appearance, in education, manners, in taste, and temperament, as two eminent men could be.” But Lincoln did admire Chase, once saying, that “Chase is about one and a half times bigger than any other man that I ever knew.”

As the war dragged on, Chase became increasingly convinced of the impossibility of Lincoln’s re-election. The Emancipation Proclamation had been satisfactory as far as it went, he felt, but it had not gone far enough. A new leader with a new approach was needed; Chase decided that it was his duty to seek the Republican nomination in 1864.

A group of Radical leaders issued a pamphlet declaring Chase as the man who best fit the party’s needs. The Chase boom, however, collapsed as Lincoln’s hold on the public became clear. Chase was unsuccessful in gaining the Republican presidential nomination in 1864, losing out to Lincoln as he had in 1860. This made Chase’s place as a Cabinet member embarrassing, and soon Chase submitted his resignation. In October 1864, Lincoln accepted it, much to the chagrin of the secretary.

Chase as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

In spite of their disagreements, Lincoln still respected Chase. When Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Roger Taney died in October 1864, Lincoln chose Chase to replace him and become the sixth chief justice in the history of the court, a position he held until his death.

In one of his first acts as Chief Justice, Chase appointed John Rock as the first African-American attorney to argue cases before the Supreme Court. Soon thereafter, President Lincoln was assassinated, and Chase administered the presidential oath to Andrew Johnson.

Chase presided over the Court during the difficult period of Reconstruction. The important tasks were to restore the Southern judicial systems and to uphold the law against congressional invasion. In December 1868, Chase confirmed the pardon of former Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Chase was unable to forge a solid majority during his tenure as Chief Justice and often found himself in dissent on important cases.

In March 1868, Chase presided over the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson in the U.S. Senate. The Chief Justice brought to the trial a much needed air of dignity and impartiality. As the first impeachment trial of a President under the Constitution, Chase realized that the procedure would set important precedents. He insisted that the Senate conduct itself as a court of law, not as a legislative body.

Meanwhile, the ambitious Chase still wanted to be president of the United States. Abandoning the Republican party, actively sought the presidential nomination of the Democratic party in 1868. He had the aid of his brilliant, beautiful and wealthy daughter, Kate Chase Sprague, who, as Washington’s most lavish hostess, sought to promote her father’s political career. In spite of the combined efforts of father and daughter, Chase never succeeded in capturing that office.

Chase became less involved in politics as his health began to fail. He suffered a stroke in 1870 that temporarily kept him from participating in the Supreme Court. In spite of poor health, he returned to the bench in 1871 and continued to preside as chief justice until his death. Toward the end of his life, he made an unsuccessful effort to secure the nomination of the Liberal Republican party for the Presidency in 1872, but they chose Horace Greeley.

Chase’s arduous duties as chief justice and fruitless exertions to gain the presidency led to rapid decline in health. Chase suffered another stroke at the home of his daughter Nettie in New York City.

Salmon Portland Chase died in New York City on May 7, 1873, at the age of sixty-five, with his two daughters at his side.

A funeral was held in the Episcopal Church of St. George in New York City. On May 11, the body was taken back to Washington, DC, for a formal state funeral, lying in state in the Old Senate Chambers on the same catafalque that had held the bier of President Lincoln. He was laid to rest at the Oak Hill Cemetery nearby.

Image: Salmon P. Chase Grave

Image: Salmon P. Chase Grave

Cincinnati, Ohio

A docent in period dress portrays Chase’s daughter,

Kate Chase Sprague, who is buried nearby.

In 1886, the State of Ohio requested that its favorite son be buried in Cincinnati. Salmon Chase and his daughter Kate, who died in poverty in 1899, rest together at the Spring Grove Cemetery outside Chase’s beloved Cincinnati.

In 1877, New York banker John Thompson named the Chase Manhattan Bank after Chase, because of his efforts in passing the National Bank Act of 1863.

Chase received one final honor in 1934, when the United States Treasury chose to place his portrait on the $10,000 bill.

SOURCES

Salmon Portland Chase

Mr. Lincoln’s White House

Wikipedia: Salmon P. Chase

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson