Wife of Boston Tea Party Participant Thomas Melville

Priscilla Scollay was born on August 15, 1755, in Boston, Massachusetts, daughter of John and Mercy Greenleaf Scollay. In 1761, along with about fifty other men, John Scollay signed a petition which was sent to King George III protesting the illegal actions of the British revenue officers. A strong supporter of colonial claims against the empire, John Scolly was chosen to Boston’s Board of Selectmen in 1764. The honor was repeated in 1773, and the following year he was made chairman, a title he held until 1790. Scollay Square in Boston is named for her family.

Thomas Melville was born in Boston, Massachusetts, January 27, 1752, the only son of Allan and Jean (Cargill) Melville. Losing his mother at the early age of eight, Thomas was raised and educated by his maternal grandmother, Mary (Abernethy) Cargill. At the age of fifteen, he entered the College of new Jersey (later Princeton University), where graduated in 1769 with a degree in theology.

Thomas Melville

Instead of becoming a minister, Melville went on a journey to Scotland, the home of his ancestors, as heir-at-law to his cousin, General Roland Melville. Thomas was welcomed there, and he received another degree from the St. Andrews College in Edinburgh. He would later receive an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard College in 1773.

Thomas Melville remained in Scotland and England two years, returning to Boston in 1773, where became a member of the Sons of Liberty organization led by Samuel Adams. From this period the cause of civil liberty engaged his attention. He took part in many of the important events preceding the revolution. He was one of the youthful disciples of Samuel Adams and John Hancock, and their friendships lasted for the rest of their lives.

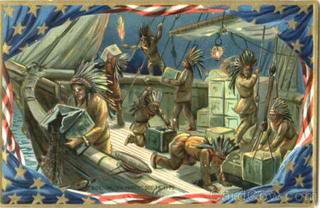

The Boston Tea Party

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which required that the requisite tax be collected within 20 days of a ship’s arrival, making December 16 the deadline. This Act gave the English East India Company a chance to avert bankruptcy by granting a monopoly on the importation of tea into the colonies. The new regulations allowed the company to sell tea to the colonists at a low price, cheaper than the smuggled tea being sold by local merchants, even including the required duty. The British reasoned that the Americans would willingly pay the tax if they were able to pay a low price for the tea.

Twenty-one-year-old Thomas Melville was one of the Mohawks (Patriots poorly disguised as Indians) who poured the tea from British ships into Boston Harbor on the night of December 16, 1773. He was one of a group of some 50 men went to Griffin’s Wharf, where three ships were moored. The vessels were boarded, the cargo carefully taken from the holds and placed on the decks. There, 342 chests were split open and thrown into the harbor. A cheering crowd on the dock shouted its approval for the brewing of this saltwater tea.

The Tea Party participants went to a great lengths to prevent anyone from keeping any of the valuable tea. However, when Melville returned home that night he found some of the tea in his shoes. He kept the tea in a little vial, and later showed it to few people, including General Lafayette, as a precious souvenir of that memorable event.

The men who took part in the event made a vow not to reveal each other’s identities. Amazingly, that vow was kept for years, even long after the American Revolution was over. John Adams, who was connected with patriotic activities in Boston but did not take part in the Tea Party, said fifty years after the event that he still did not know for sure who was involved.

Other Tea Parties were quickly staged in other port cities in America, and tended to polarize the sides in the widening dispute. As a result, Patriots and Loyalists (British supporters) became more ardent about their views.

Thomas Melville married Priscilla Scollay in Boston on August 20, 1774. They would have eleven children together. Their grandson was author Herman Melville, son of Thomas’ and Priscilla’s second son Allan.

The Boston Tea Party

December 16, 1773

Melville’s Military Career

General Joseph Warren selected Melville as one of his aides, shortly before Warren’s death at the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. Melville received the rank of Captain in 1776 in the Massachusetts Artillery Regiment under the command of Colonel Thomas Crafts who was also a Boston Tea Party participant. Just a year later, he was promoted to Major of the same unit. For a time he was on garrison duty in and around Boston.

When the British evacuated that city in 1776, a portion of their fleet was left in Nantasket Roads, Massachusetts, to prevent any British vessels from entering the harbor and falling into the hands of the Patriots. During his service at Nantasket Roadsin May 1776, Melville’s regiment was positioned to prevent British troops from entering Boston Harbor. During one such attempt, Major Melville aimed and fired the first cannon, which was followed by others and forced the enemy to retreat.

Melville served with Colonel Craft’s regiment in 1777 in Rhode Island, and was with the regiment in 1779 at the Battle of Rhode Island under General John Sullivan. He also served on the committee of correspondence and on the town committee to obtain its quota of troops for the Continental Army.

Melville’s Political Career

Thomas Melville’s long career began with his involvement with Boston’s Committee of Correspondence. Melville’s political career continued as the elected State Representative from the city of Boston, the post to which he was continuously re-elected. In 1779, he was chosen one of the fire wardens of Boston for a period of forty-seven years. One of the engines and companies bore his name and ever honored his memory.

Before the Federal Constitution was adopted and the state government was established, one of the highest executive appointments in the port of Boston was the Naval Officer post, for which Melville was chosen by the Massachusetts legislature three years in a row, beginning in 1787.

When the constitution was adopted, the appointment of customs house officers was transferred to the president of the United States. For the port of Boston, President George Washington appointed General Benjamin Lincoln as collector, James Lowell as naval officer, and Major Thomas Melville as surveyor and inspector.

A few years later, President James Madison appointed Melville Naval Officer again. He continued to hold this post under successive presidents, through John Quincy Adams. In 1829, Melville fell victim to the doctrine “to the victors belong the spoils” – he was removed from office by President Andrew Jackson. The old hero bitterly resented his removal and often referred to it as the “bitterest insult” of his life.

When Melville retired, he was presented with a silver pitcher as a token of personal respect and a public testimonial of his faithful services. The Massachusetts legislature appointed him a director of the State Bank and other public institutions, and he was chosen as delegate to the convention that revised the state constitution.

Thomas Melville, who refused to change the style of his clothing or manners to fit the times, was depicted in Oliver Wendell Holmes’ poem, The Last Leaf. He was known among these as “the last of the cocked hats” – until his death he always wore a three-cornered cocked hat and knee breeches. He had many warm friends among the military and public men of his day.

Thomas Melville died peacefully at his home in Boston, on September, 16, 1832, at the age of eighty-two.

Priscilla Scollay Melville survived her husband with whom she had spent a congenial, happy life for fifty-eight years.

Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick, Billy Budd, Typhee, and Omoo, was their grandson. Earlier members of the family spelled the name Melvill. Herman’s mother and her children began to spell the family name with a final e following Allan Melville’s death.

SOURCES

Melville Family Memoirs

The Scollays and Scollay Square

Boston Tea Party Historical Society

Who Took Part in the Boston Tea Party?