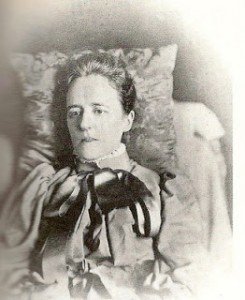

Wife of Confederate General Jerome Bonaparte Robertson

Jerome Bonaparte Robertson was born on March 14, 1815, in Woodford County, Kentucky, the son of Cornelius and Clarissa Hill (Keech) Robertson. His father, a Scottish immigrant, died in 1819, leaving his mother almost penniless. Unable to properly support her family, she apprenticed eight-year-old Jerome to a hatter, who moved to St. Louis in 1824, and took the boy with him.

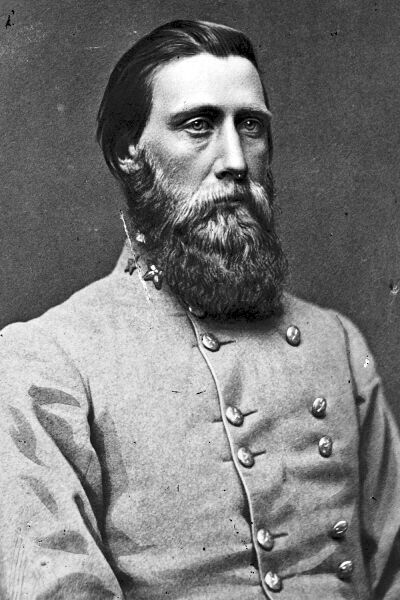

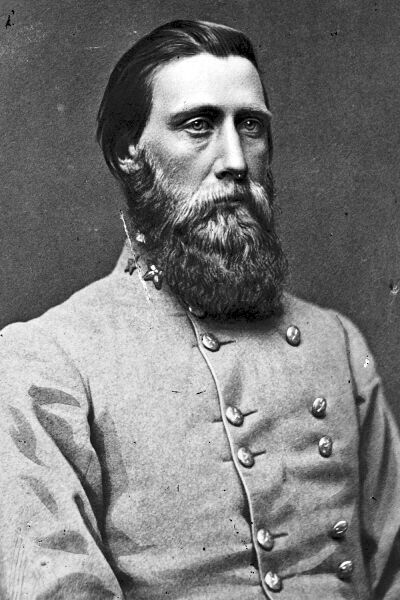

Jerome Robertson

Despite many hardships, Jerome Robertson eventually studied medicine at Transylvania University, where he graduated in 1835. With the Texas Revolution emerging as a national topic, Robertson joined a company of Kentucky volunteers as a lieutenant and made plans to travel to Texas. However, they were delayed in New Orleans and did not arrive in Texas until September 1836. There, he joined the Army of Texas and was commissioned as a captain.

In 1837, Robertson returned to Kentucky and married Mary Elizabeth Cummins, daughter of Moses Cummins. Jerome and Mary had three children, one of whom died in infancy. His son, Felix Huston Robertson, was a brigadier general in the Confederate Army.

With Mary, her father, his brother James, and his uncle Willet Holmes, Robertson returned to Texas in December 1837. He bought land and settled in Washington-on-the Brazos, where he began his medical practice. He was coroner of Washington County in 1838-39, mayor of Washington-on-the-Brazos in 1839-40, and postmaster from 1841 to 1843.

Robertson became well known as an Indian fighter; he served every year for six years in Indian or Mexican campaigns. He also served in the military forces that helped repel two invasions by the Mexican army in 1842.

Jerome Robertson moved to Independence, Texas, in the 1840s. He took an active political and military role in the Texas independence movement. He served in both houses of the Texas legislature in Austin in the late 1840s, during which time he maintained this residence in Independence. In the mid-1850s, the family moved to a nearby plantation and most likely rented the house, which was typical of landed property owners in the area.

The Civil War

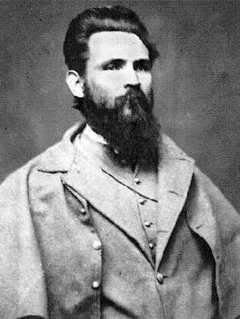

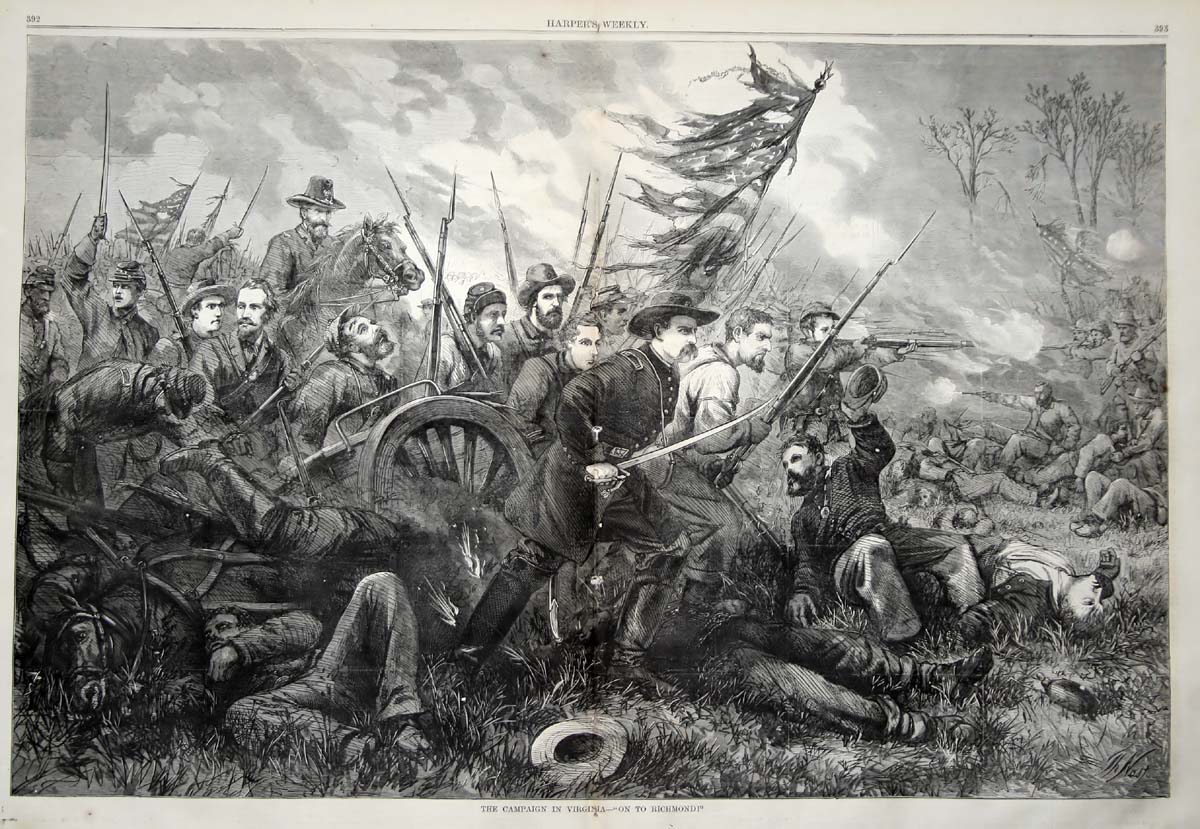

Jerome Robertson was a delegate to the Secession Convention in January 1861. At the age of forty-one, he one of the first Texans to raise a company for Confederate military service. Arriving in Richmond, his company was made part of the 5th Texas volunteer regiment, which was brigaded with other Texas regiments in Richmond. This only brigade of Texans in the Virginia army would soon win fame as Hood’s Texas Brigade.

As the fighting intensified, Robertson won rapid promotion. In November 1861, he was made lieutenant colonel and on June 1, 1862, received a commission as a full colonel and commanded the Fifth Texas Infantry in the brigade of General John Bell Hood. Robertson became popular with his soldiers due to his unusual concern for their welfare, giving rise to his nickname, Aunt Polly.

In early June 1862, J.J. Archer, the first colonel of the 5th Texas, was given his own brigade, and Robertson was promoted to take his place at the head of the regiment in time for the Seven Days Battles in the Peninsula Campaign. There, in the brigade’s first full-scale battle, the Texans won glory in their triumphant assault at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, where Robertson was wounded in the shoulder.

He was back in command of the 5th Texas two months later at Second Manassas, where the Texas Brigade added to its reputation by spearheading another Confederate attack. At one point in the action, finding that the right of his regiment had gone ahead unsupported, Robertson did not recall the overenthusiastic companies, but instead sent the rest of the regiment to follow them. A few minutes later, Robertson was shot in the groin at the head of his regiment, which was then out in front of the whole Rebel army.

Robertson tried to stay with the army during the subsequent Maryland Campaign, but at South Mountain he had to be taken off the field after being overcome by exhaustion and the effects of his recent wound. He was too weak to fight at the Battle of Sharpsburg three days later. Nevertheless, he was promoted to brigadier general on November 1, 1862, and given command of the Texas Brigade, taking the place of that other Kentuckian-turned-Texan, Major General John Bell Hood.

Robertson wouldn’t have a chance to prove what he could do with a full brigade until the next summer at Gettysburg, however. At Fredericksburg, the division was unthreatened, and the Texas Brigade lost only six men. At Chancellorsville, Robertson’s men were with the rest of Hood’s division at Suffolk, out of harm’s way.

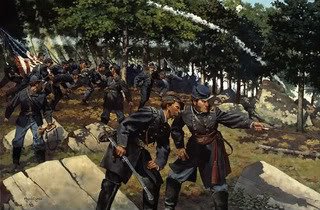

On July 2, 1863, the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Robertson’s Texas Brigade of Hood’s Division arrived on the field at Gettysburg at 4 pm. At the time of the battle, the brigade consisted of 1834 officers and men. The lone Arkansas unit, the 3rd Infantry, served at Gettysburg with the 1st, 4th, and 5th Texas. Their strengths were: 1st Texas, 452 officers and men; 4th Texas, 440 officers and men; and 5th Texas, 434 officers and men; 3rd Arkansas, 508 officers and men.

Robertson’s brigade was deployed in the first line for Hood’s attack, to the left of General Evander Law’s brigade. About 4:30 pm, Law’s brigade advanced. Robertson and his men sprang forward immediately afterward. Robertson had been ordered to keep his right closed on Law and keep his left on the Emmitsburg Road. Law, however, had sent his brigade almost directly east against the Round Tops, and Robertson soon found that his brigade had to either abandon the road or disconnect himself from Law.

Reasoning that General Lafayette McLaws was scheduled to strike soon on his left, Robertson decided to break with the road rather than with Law, and he directed his own brigade eastward, directly at the Devil’s Den. During the advance over hundreds of yards of broken terrain, “exposed to a destructive fire of canister, grape, and shell,” the distance between the wings of his brigade lengthened, and Robertson lost contact with his two right regiments, the 4th and 5th Texas Regiments. He was informed that they had drifted into the middle of Law’s brigade and could not be removed, so he sent a request to Law to look after them.

The 1st Texas and the 3rd Arkansas

Robertson concentrated on his two left regiments – the 1st Texas and the 3rd Arkansas – at the base of Devil’s Den and in the Rose Woods. Before long, General Robertson became aware that McLaws’ brigades were not appearing on his left as he expected, and he sent back for reinforcements. This was complicated by the fact that General Hood was being carried off the field with a shredded right arm, so Robertson sent his requests to corps commander Lt. General James Longstreet and General Henry Benning in his rear. The latter two brigades came up on either side of Robertson’s two regiments.

One veteran of the battle described Devil’s Den as, “a wild, rocky labyrinth which, from its weird, uncanny features, has long been called by the people of the vicinity the ‘Devils Den.’ Large rocks from six to fifteen feet high are thrown together in confusion over a considerable area and yet so disposed as to leave everywhere among them siding passages carpeted with moss. Many of the recesses are never visited by the sunshine, and a cavernous coolness pervades the air within it.”

Pastures around the base of the Den were filled with piles of rocks and large boulders that caused battle formations to fragment. Officers lost control of their commands and soldiers lost their way in this wild garden of stone. Men scrambled behind boulders for protection from the shower of bullets, shell and canister.

The Triangular Field

Gettysburg Battlefield

On the afternoon of July 2, the huge granite formations of Devil’s Den provided height and protection for Captain James Smith’s 4th New York Artillery stationed there. Smith and his lieutenants hoped that if the Confederates attacked they would do so on the west side through a triangular field and not from another direction. Otherwise, they would be trapped.

The 4th New York Battery initially dueled with Confederate batteries near the Emmitsburg Road three quarters of a mile to the west until Generals Robertson and Henry Benning and their brigades closed in on their position.

The fight for Devil’s Den was confused and desperate as both sides struggled to occupy the mass of boulders. Charge and countercharge in these fields, flanking fire from the 17th Maine in the Wheatfield, and artillery fire from Smith’s battery all took a frightful toll on these Rebel soldiers.

Repeated charges by the 1st Texas through the triangular field wore down Smith’s artillerymen. When it appeared that his guns were in danger of being captured, a desperate counterattack by the 124th New York Infantry stalled the southern assault.

The agressive Union defense made General Robertson believe that he was outnumbered six to one, but he rallied his Texans with the 3rd Arkansas Infantry for one last effort. Shouting the rebel yell, the 1st Texas charged up the triangular field to finally take the summit and the ridge above. They swarmed over Devil’s Den and took three of Smith’s guns. One enthusiastic Texan stood upon one of the cannon and triumphantly waved the flag of the 1st Texas at the retreating northerners.

As the sun began to set, Houck’s Ridge and Devil’s Den were occupied by boys from the South, but the stress of battle and heat had taken a toll on Robertson’s troops. Finally, at someone’s order the 1st Texas and 3d Arkansas regiments pulled back and reformed on the shoulder of Big Round Top southeast of Devil’s Den.

The cost had been enormous, a price the Confederate army could ill-afford. In the 3rd Arkansas, 41 were killed and 141 wounded or missing, thirty-eight percent of the 426 men engaged. The 1st Texas had suffered greatly in the Triangular Field south of the Devil’s Den. Official reports list 97 casualties, but other accounts state that 125 men lay in that field, including two captains, two lieutenants, seven sergeants and seven corporals.

The loss was particularly heavy among officers. General Longstreet would note that the July 2 action was “the best three hours of fighting ever done by any troops on any battlefield.”

The 3rd Arkansas and 1st Texas had met an overwhelming force, fought without breaking, and with the help of two Georgia brigades had taken the Rose Woods and Devil’s Den. This would end the battle for the 3rd Arkansas, but the 1st Texas would also help repel General Elon Farnsworth’s ill-fated and ill-conceived cavalry charge late on July 3 on the far right of the Confederate line near the Slyder farm.

Late in the evening, Robertson was wounded above the right knee and couldn’t walk. He left the brigade with his senior colonel and retired 200 yards to tend his wound. At the end of the day, Robertson’s men slept in their positions around Devil’s Den.

The 4th and 5th Texas

Having been separated from the other half of their brigade on the afternoon of July 2, the 4th and 5th Texas followed Law’s soldiers over the northwest shoulder of Big Round Top and headlong into Little Round Top. They hit the Union brigade of Colonel Strong Vincent, which consisted of the 16th Michigan, 44th New York, 83rd Pennsylvania, and the 20th Maine. Although the fight between the 20th Maine and the 15th and 47th Alabama receives most of the attention, the fighting between the 4th and 5th Texas and the boys from Michigan and New York was no less earnest or deadly.

The 4th Texas was on the left of the Fifth Texas as it attempted to flank the right of the 16th Michigan. The third and final attempt to flank the 16th Michigan ended with the downhill charge of the 140th New York and its three sister regiments of Weed’s Union brigade. The 4th Texas had made its way to within 20 yards and no closer.

Following their last attempt to flank the line, the soldiers took cover behind the rocks and continued the fight. Eventually, the 4th and 5th Texas retreated to the rise above Devil’s Den and took stock of their losses. The 4th Texas had lost 112 men, dead, missing or wounded, 27% of the regiment. The 5th Texas sustained a 51.6% casualty rate, which included 54 dead.

On July 3, at 2 am, the 1st Texas and 3d Arkansas were moved to the right and joined the 4th and 5th Texas on the northwest spur of Big Round Top. Three regiments occupied the breastworks there all day, skirmishing hotly with Union sharpshooters. Early in the day, the 1st Texas was sent to confront the Union Cavalry threatening the right Confederate flank.

At daylight on July 3, the scattered remnants of Robertson’s Brigade were unified and occupied a sector along Plum Run between Devil’s Den and Big Round Top. This would become part of the main Confederate defense line thoughout the day. While Lee was launching Pickett’s Charge against the Union center, the Confederate right was relatively quiet. Sniper fire persisted throughout the day, and occasionally a shell would explode amidst the sparse ranks of the Texans.

Late in the afternoon, Hood’s Division withdrew from its forward position to a line near the Emmitsburg Road. Here they remained through July 4, awaiting a Federal attack that never came. The Texas Brigade moved from its position during the night of July 4. The march was slowed by heavy rains, high winds, and rutted roads. On July 5 at about 5 am, they began the march to Hagerstown Md.

In September 1863, Robertson and his Texans went with General James Longstreet to Tennessee, where the brigade fought with distinction at the Battle of Chickamauga. However, Robertson’s performance in the subsequent East Tennessee Campaign invoked the wrath of Longstreet and division commander Micah Jenkins. Robertson had joined the other brigadiers in the division in supporting Evander McIvor Law as division commander, instead of Longstreet’s protege Jenkins.

Longstreet filed formal court-martial charges against Robertson, alleging delinquency of duty, and accusing him of pessimistic remarks.

On December 18, General Micah Jenkins preferred charges of “conduct highly prejudicial to good order and military discipline” against Robertson. These charges stemmed from detrimental remarks Robertson had supposedly made about Jenkins’ leadership and judgment following a recent order to pursue marauding Federal cavalry.

According to Miles V. Smith of the Fourth Texas, “the brigade was called on often during the winter to race out after Federal cavalry over ice and snow with no shoes.” When ordered to repel a cavalry raid under bad weather conditions, Robertson protested and remarked that “he didn’t see any reason to have his men run after every cavalryman that came by.” A junior officer reported this remark to Jenkins.

On December 23, Longstreet relieved Robertson of command of the Texas Brigade and had him arrested and taken to Bristol, Tennessee, to “await the assembling of a court for the trial of his case.” The hardships experienced by the Texas Brigade at this time were exacerbated by their concern over the fate of General Robertson.

On January 6, 1864, all officers present for duty in the Fourth and Fifth Texas signed a petition to the Secretary of War asking that General Robertson be restored to the command of the brigade. About the same time, the Third Arkansas forwarded to Richmond a similar petition.

On February 3, a court martial was at last convened at Russellville, Tennessee, to review the charges against Robertson. General Simon Bolivar Buckner presided over the court, which included General John Gregg, who had been rescued by the Texas Brigade after his severe wounding at the Battle of Chickamauga.

On February 25, the court acquitted Robertson of “improper motives” but disapproved “his conduct.” The court reprimanded Robertson and permanently relieved him of command of the Texas Brigade, which he had commanded longer than any other officer.

After his trial, Robertson went to Richmond to await a new assignment. While there, he received much support from his fellow division officers. Robertson was reprimanded and transferred to Texas, where he commanded the state reserve forces until the end of the war. He remained in Texas after the war.

On April 9, 1864, just before leaving Richmond, Robertson wrote a poignant farewell to his old brigade. The last sentence was, “With a mind saddened by the remembrances of ties broken, and with the prayer that God, in his mercy, will guard, protect and bless you, I bid you farewell.” With this, Robertson left the Army of Northern Virginia and his beloved troops.

On April 10, General Evander Law wrote to Robertson, “I feel that I can ask nothing better for you in the future, than that your happiness and prosperity may be commensurate with the gallantry, ability, and patriotism that you have displayed in the service.”

On April 11, General John Bell Hood wrote of Robertson:

“I know him to be an officer of great energy and faithful in the discharge of his duties. He has great experience as an officer and has taken part in many battles. His troops are very much attached to him.”

After the Confederate surrender, Robertson returned to his home in Independence and resumed his medical practice.

Mary Cummins Robertson died in 1868.

Robertson reentered politics in 1874, being named as superintendent of the Texas Bureau of Immigration. He also served as passenger and emigration agent for the Houston and Texas Central Railroad in 1876.

In 1878, Robertson remarried widow Hattie Hendley Hook and moved to Waco a year later. There, he continued to promote railroad construction in West Texas. He was also an organizer of the Hood’s Texas Brigade Association, which he served as president several times.

General Jerome Bonaparte Robertson died on January 7, 1890, and was buried at Independence, next to his first wife and his mother. In 1894, his son had all three bodies moved to Oakwood Cemetery in Waco.

SOURCES

Devil’s Den

Handbook of Texas

Wikipedia: Jerome B. Robertson

General Jerome B. Robertson House

The Story of the Battle of Gettysburg

The Trans-Mississippi Units at Gettysburg

The Story of the 3rd Arkansas at Gettysburg

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General Jerome Bonaparte Robertson

An Illustrated History of the Fourth Texas Infantry