Wife of Confederate Major General William Henry Fitzhugh Lee

Charlotte Wickham was the child of George Wickham of the U.S. Navy and Charlotte Carter Wickham, daughter of Williams Carter of Shirley Plantation. This estate, with its attractive mansion in Charles City County, Virginia has been the seat of the Carter and Hill Families since 1638. Charlotte’s mother died while she was a baby, so Charlotte was raised at Shirley.

Image: Shirley Plantation

Image: Shirley Plantation

Childhood home of Charlotte Lee

In earlier times, guests arrived by boat along the James River, where they looked up to see the front of this perfectly proportioned Georgian Colonial house. Shirley Plantation was begun in 1613, making it the oldest in Virginia, and to this day its 700 acres are sown with seeds each spring.

Charlotte Wickham lived a life of wealth, yet her life was filled with trauma, from the untimely deaths of her parents, to the loss of both of her infant children, to finally her own death in her early twenties. As a descendant of some of Virginia’s most prominent families and living on one of the area’s finest estates, Charlotte traveled in an elite social circle as she entered adulthood.

William Henry Fitzhugh Lee was born at the family home of Arlington House in northern Virginia on May 31, 1837, the son of Robert Edward and Mary Custis Lee. He was a lively and likable child, whom his father called a “large heavy fellow” who needed to be watched closely. He was named for his mother’s uncle, William Henry Fitzhugh of Ravensworth. His nickname was Rooney.

Rooney had his heart set on attending West Point, but was unable to do so because of regulations prohibiting brothers from attending the academy at the same time – his older brother, Custis, was already a cadet there. Instead, he reluctantly entered Harvard in 1854 as one of only three Virginians at the school.

At Harvard, he was popular with Boston society and joined the school’s crew team, but instead of graduating, he secured a commission in 1857, with the aid of General Winfield Scott, as a Second lieutenant in the 6th Infantry and fought in the Utah Expedition of 1858 under Albert Sidney Johnston, and subsequently served in California. After two years of service, he opted for the life of a Virginia planter and resigned from the army in 1859.

On March 23, 1859, Charlotte Wickham married Rooney Lee at Shirley Plantation. It was in the same great hall where Rooney’s grandparents were married – his grandmother was born and reared there. The groom’s father, Robert E. Lee, laughed a good deal, but limited himself to two glasses of Madeira. He was also one of the trustees for Charlotte’s generous marriage settlement.

Charlotte and Rooney settled down to farm at the old Custis estate, White House Plantation, a 4000-acre estate on the Pamunkey River in New Kent County, Virginia, which Rooney had inherited from his maternal grandfather, George Washington Parke Custis, in 1857. It had been the home of Martha Custis Washington prior to her marriage. Rooney spent most of his time refurbishing the plantation, which had fallen into disrepair, and tilling the land.

In March 1860, Charlotte gave birth to Robert E. Lee’s first grandchild, Robert Edward Lee. The flattered grandfather wrote:

I wish I could offer him a more worthy name and a better example. He must elevate the first, and make use of the latter to avoid the errors I have committed. I also expressed the thought that under the circumstances you might like to name him after his great-grandfather, and wish you both, ‘upon mature consideration,’ to follow your inclinations and judgment. I should love him all the same, and nothing could make me love you two more than I do.

Charlotte’s health was never robust; the son she bore in March 1860 and the daughter she delivered two and a half years later, Mary Custis Lee, both died in infancy.

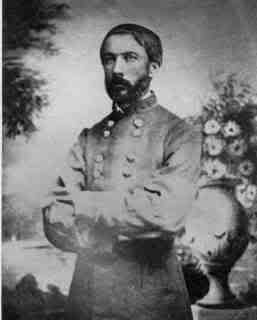

Image: The Generals Lee

Image: The Generals Lee

General Robert E. Lee and his sons: George Washington Custis Lee, William Henry Fitzhugh (Rooney) Lee (center) and Robert E. Lee, Jr.

When the Civil War began, Rooney Lee organized a company of cavalry in New Kent County, and joined the Confederate Army as a captain. He was soon promoted to major. His unit accompanied him to a training camp north of Richmond, where it formed the nucleus of the Ninth Virginia Regiment. During the summer of 1861, he served in Western Virginia in Brigadier General William Loring’s cavalry. The imposing 6’4″ son of Robert E. Lee received command of the Ninth Virginia Cavalry regiment in early 1862.

Meanwhile, Charlotte remained at White House. Her mother-in-law, Mary Randolph Custis Lee suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, which became increasingly debilitating with advancing age. She was staying with Charlotte at White House when Union troops under General George B. McClellan took White House Landing as a supply base during the Peninsula Campaign in 1862, a failed attempt to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond.

In a gentlemanly gesture, General McClellan made arrangements for safe passage for Mary Lee and her family through the Union lines, shortly before the enemy seized and occupied their home. She relocated to Richmond, where she and her daughters lived at 707 East Franklin Street for the bulk of the War.

When they left on May 11, 1862, Mary Lee pinned a note on the front door, saying: “Northern soldiers who profess to reverence Washington, forbear to desecrate the home of his first married life, the property of his wife, now owned by her descendants.” It was later discovered that someone had written under the note: “Lady, a Northern officer has protected your property in sight of the enemy, and at the request of your overseer.”

Though the Federal army stored supplies on the estate, General McClellan gave specific protection to the residence, but in the confusion after the Union defeat at Gaines’ Mill on June 27, 1862, the manor house at White House was set afire. When Stuart’s advance guard reached White House landing on the morning of June 29, Rooney Lee discovered that his home had been burned to the ground.

On June 1, 1862, General Robert E. Lee was assigned to command the Army of Northern Virginia, replacing the recently wounded Joseph E. Johnston. Lee’s first task was to ascertain the position of his enemy, which was poised to besiege Richmond; he especially wanted information about the location and strength of McClellan’s right flank north of the Chickahominy River.

Lee ordered cavalry commander General J.E.B. Stuart, under whom Rooney Lee was serving at that time, to lead an expedition to the enemy’s rear and to return as quickly as possible with the needed intelligence. Stuart conducted the operation at the head of a picked force almost 1,000 strong. Determined that his best officers would accompany him, he included Rooney Lee’s regiment in this force.

Leaving Hanover Court House on June 12, Stuart crossed the Chickahominy and slipped around McClellan’s right. In a typically audacious move that exceeded his orders, Stuart made a complete circuit of the Union army, returning to headquarters three days and 150 miles later with word that the Union right was unanchored and vulnerable to attack. Grateful for the news, Robert E. Lee launched a series of attacks so threatening to his position that McClellan retreated in haste to the James River.

Rooney had figured prominently in the expedition, which won Stuart and his command great fame. Rooney Lee had helped Stuart find a way to re-cross the rain-swollen Chickahominy near the journey’s end, averting a threat to the safety of the entire raiding column. In Stuart’s report, Rooney received high praise.

During the Second Manassas Campaign, Rooney played a leading role in Stuart’s well-crafted attack on General John Pope’s supply base at Catlett’s Station on August 22, 1862, capturing a paymaster’s safe full of Yankee greenbacks. The battle ended as the first had – with the defeat of the Union army and its headlong retreat to the defenses of Washington.

With Pope’s army bottled up in Washington, General Lee put into action a long-planned invasion of Maryland. His army—its front, flanks, and rear covered by Stuart’s troopers—began to cross the Potomac on September 4, then headed through the mountains west of Frederick. En route, the cavalry tangled with pursuing horsemen in the rear.

In one of these actions – outside Boonsboro, Maryland, on September 15 – Rooney Lee’s horse was killed and fell on him, knocking him unconscious. For a time partially paralyzed, Rooney finally managed to crawl to safety, but his participation in the campaign was over.

Rooney—fully recovered from his own injuries—took command of his wounded cousin Fitz Lee’s brigade. In October 1862, he led it on another daring raid inside Union lines. Stuart’s troopers tore up railroads, overran supply bases, and denuded every farm and stable along their route, which carried them as far north as Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. On the return march, however, they barely avoided being cut off by pursuit forces near the mouth of the Monocacy River.

At a critical point, Rooney Lee, commanding a detachment well in advance of General Stuart’s main body, bluffed his way past a large infantry force guarding the fords at which Stuart planned to cross. The ruse enabled the raiders to reach the south bank before other, larger enemy forces could overtake them. Stuart praised his subordinate’s timely combination of coolness and cunning. A more tangible expression of his regard came a few weeks later, when Rooney was promoted to brigadier general in command of a brigade that included his 9th Virginia.

The middle years of the Civil War brought the Lee family a slew of tragedies. In the fall of 1862, typhoid fever claimed the lives of Lee’s youngest daughter, Annie, and his only grandson, Rooney’s son Robert. Charlotte gave birth to a sickly daughter, who died in December. Meanwhile, Mary Lee’s declining health and Charlotte’s ongoing battle with tuberculosis continually worried the family.

In May 1863, Rooney served conspicuously in the fighting that culminated in the defeat of the Union army at Chancellorsville. That campaign began with the new Union commander, Joseph Hooker, attempting to march into the rear of the Army of Northern Virginia. To exploit his turning-movement, Hooker dispatched most of his cavalry under General George Stoneman on a raid toward Richmond.

Because the majority of Stuart’s command remained in close support of the main army, only Rooney Lee, with two regiments, was available to tail Stoneman. He did an amazing job, bringing one of Stoneman’s wings to a halt and forcing its retreat. Then he turned against the other column, harassing it every step of the way and preventing it from inflicting critical damage to rebel resources.

The cavalry of the Army of the Potomac had greatly improved during the first half of 1863. On the morning of June 9, thousands of Union horsemen swept down on Stuart’s camps near Brandy Station, Virginia. Rooney Lee was trying to stabilize Stuart’s upper flank, the scene of the initial attack. The position was secured, but at the height of the action Rooney took a rifle ball in the thigh and was forced to the rear for medical attention.

It was common for the wealthy to recuperate from battlefield injuries at a family estate, so Rooney was taken to Hickory Hill Plantation in Hanover County, where Charlotte’s uncle William Fanning Wickham resided with his family, which included his son, Confederate general Williams Carter Wickham.

Rooney was put under the care of his brother, Robert E. Lee, Jr., and his wound began to heal. Charlotte joined them, as well as Rooney’s mother and sisters, who came up from Richmond. Rooney occupied “the office,” a small building in the yard, while Robert slept in the room adjoining and became an expert nurse.

In a letter to Charlotte, written on June 11th, General Lee wrote:

I am so grieved, my dear daughter, to send Fitzhugh [Rooney] to you wounded. But I am so grateful that his wound is of a character to give us full hope of a speedy recovery. With his youth and strength to aid him, and your tender care to nurse him, I trust he will soon be well again.

On the morning of June 26, 1863, the family at Hickory Hill were finishing breakfast and moving out to the front porch, when they were surprised to hear two or three shots down in the direction of the outer gate, where there was a large grove of hickory trees. The Wickhams thought someone must be hunting squirrels, as there were many in those woods, so Robert was asked to run down and stop whoever was shooting them.

Grabbing his hat, Robert headed off, but had gone only a hundred yards toward the grove when he saw five or six Federal cavalrymen coming up at a gallop to the gate. Realizing what it meant, he rushed back to the office and told his brother. Rooney ordered his brother to leave at once, so he ran away, clambered over the fence and ducked behind a thick hedge, just as he heard the “tramp and clank” of a large body of troopers riding up.

Behind the hedge, Robert crept along until he reached the woods, where he was safe. From a nearby hill, he ascertained that there was a large raiding party of Federal cavalry on the main road; heavy smoke ascending from the Court House, about three miles away, told him that they were burning the railroad buildings there.

After waiting until he thought it was safe, Robert worked his way back toward the house to find out what was going on. He took advantage of the shrubbery in the old garden behind the house, there were still numerous Union soldiers standing, sitting, and walking around. He saw Rooney being brought out from the office on a mattress and placed in the family carriage, and saw them driven away, a soldier on the box and a mounted guard surrounding him.

Rooney was sent by boat to Fort Monroe, and placed in the hospital there and was allowed liberties on his assurance that he would not attempt to escape, but on July 15, he had been ordered into close confinement and was threatened with death by hanging if the Confederate authorities executed Captains W. H. Sawyer and John Flinn, who were among the officers held at Libby Prison in Richmond. The Federal threat prevented the execution of Sawyer and Flinn, so Rooney’s life was spared, though he was kept in close captivity for several weeks.

However, Charlotte became traumatized after witnessing her husband’s capture, with the excessive grief causing her to become seriously ill. It was decided to take her to a resort of her choosing, the Hot Springs in Alleghany County. About July 17, she and her mother-in-law started for the resort in a box car fitted up as a bedroom, but the vacation was not successful.

Charlotte’s condition grew worse, and her family began to fear for her life. When the news reached Rooney that Charlotte might be dying, he asked for a parole of forty-eight hours to visit her, with the assurance that his brother Custis, his equal in rank, would stand hostage for him, but his request “was curtly and peremptorily refused.”

General Lee tried to comfort Charlotte with the assurance that her husband would be well cared for, urging:

You must not be sick while Fitzhugh [Rooney] is away, or he will be more restless under his separation. Get strong and hearty by his return, that he may the more rejoice at the sight of you… I can appreciate your distress at Fitzhugh’s situation. I deeply sympathize with it, and in the lone hours of the night, I groan in sorrow at his captivity and separation from you. But we must bear it, exercise all our patience, and do nothing to aggravate the evil.

The restraints on Rooney were gradually relaxed, but he received so much attention from friends and visitors at Fort Monroe that the authorities decided to send him to Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie, where he would not be lionized. But the orders were modified to permit his transfer to Fort Lafayette in New York harbor, allowing him to leave on November 13, 1863.

But Charlotte’s condition became daily more serious. By Christmastime, the news from her was somewhat more encouraging, and her family was hopeful that she might recover.

Then, on December 26, 1863, after a period of relatively good health, Charlotte Lee died unexpectedly while her husband remained a prisoner of the Union Army.

By that time, Rooney had been transferred to Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor as a hostage for two Union officers confined in Richmond’s Libby Prison. Confederate authorities had announced plans to hang the two in retaliation for two Confederate officers who had been executed as spies in Kentucky. The administration of Abraham Lincoln let it be known that if the prisoners in Libby were hanged, Rooney Lee would share their fate.

The following five months were a nerve-wracking period for Rooney Lee and his family. His father, although arguing privately against hanging anyone involved, made no personal appeal for his son’s release. Eventually, cooler heads prevailed, an exchange of prisoners was worked out. Rooney had spent nine months as a prisoner of war before being exchanged in March 1864.

Image: Review at Moss Neck

Image: Review at Moss Neck

Review of General Rooney Lee’s Regiment at Moss Neck Mansion on January 20, 1863. The inspection party (right) shows General Robert E. Lee in his blue cape, flanked on the left by General Stonewall Jackson directly under the battle flag, on the far left of the group is General Rooney Lee, closest to his troops. On the right, in the red-lined cape with a plume in his hat is General Jeb Stuart. Directly behind him is General James Longstreet.

Grief stricken over the loss of his wife and two children, Rooney turned to his father for support and guidance. The following letter is an outstanding example of Lee’s character and his relationship with his children. Lee’s letters to his children typically preach discipline, duty and responsibility, while, at the same time, tempering strictness with extraordinary tenderness and affection.

Robert E. Lee to Rooney Lee:

Camp Orange Co: 24 Apl ’64

I rec[eive]d last night my dear Son your letter of the 22nd. It has given me great Comfort. God knows how I loved your dear dear wife, how Sweet her memory is to me, and how I mourn her loss. My grief Could not be greater if you had been taken from me. You were both equally dear to me. My heart is too full to Speak on this Subject, nor Can I write. But my grief is not for her, but for ourselves. She is brighter and happier than ever, Safe from all evil and awaiting us in her heavenly abode. May God in his Mercy enable us to join her in eternal praise to our Lord and Saviour. Let us humbly bow ourselves before Him and offer perpetual prayer for pardon and forgiveness!But we Cannot indulge in grief however mournful yet pleasing. Our Country demands all our thoughts, all our energies. To resist the powerful Combination now forming against us, will require every man at his place. If victorious we have everything to hope for in the future. If defeated nothing will be left us to live for. I have not heard what action has been taken by the Dept in reference to my recommendations Concerning the organization of the Cav[alr]y. But we have no time to wait and you had better join your brigade. This week will in all probability bring us active work and we must strike fast and strong. My whole trust is in God, and I am ready for whatever he may ordain. May he guide, guard and Strengthen us is my Constant prayer.

Your devoted father

R. E. Lee

By late April, Rooney had returned to duty with his father’s army, and was welcomed back heartily by all who loved and respected him. He was also greeted with a promotion to major general on April 23, 1864, making him the youngest Confederate to hold that rank. At Stuart’s recommendation, General Lee had sanctioned the formation of a third cavalry division—made up of elements formerly assigned to the other two—and it had been given to Rooney.

In early May 1864, the spring campaign pitted Robert E. Lee against Ulysses S. Grant, the newly appointed commanding general of all United States forces. Rooney and his men did their utmost to slow Grant’s movement toward Richmond, which began on May 4. In the fighting that followed—in the Wilderness, at Todd’s Tavern, and at Spotsylvania Court House – they gave a strong account of themselves against the Union horsemen led by Major General Philip Sheridan.

In the summer of 1864, Rooney’s division supported the main army, following Grant toward his new objective, Petersburg. Early in the Petersburg Campaign, Rooney chased down cavalry raiders under Brigadier General James H. Wilson and, during Wilson’s return march, helped trap him and capture hundreds of his men. He fought well in the July and August battles at Deep Bottom, and in mid-September he effectively supported the attack on the Union army’s cattle herd outside Petersburg, which resulted in the capture of almost 2500 head of cattle.

During the final year of the war, as the ranks of Confederate officers thinned through attrition, Rooney’s role mushroomed. He performed well at the outset of the Appomattox Campaign. At Five Forks, April 1, 1865, the Confederate left and center quickly went under, but Rooney’s division held its position until dark, when they were finally able to withdraw. He cobbled together what remained of his scattered command and fought stubbornly during the subsequent retreat toward Appomattox Court House.

Late on April 8, 1865, General Sheridan’s pursuing horsemen managed to get ahead of the Confederates and cut off their retreat. In the climactic fighting the next day, General Rooney Lee was forced to surrender what remained of his division – only 300 officers and men, one-tenth the size of the command during the Petersburg Campaign.

After the war, Rooney returned to his plantation, the White House, where he rebuilt his destroyed home, farmed the land, and served as president of the Virginia Agricultural Society. He married Mary Tabb Bolling on November 28, 1867, and they had two sons – Robert Edward Lee III and George Bolling Lee, both of whom reached adulthood. Long after his childhood days at Arlington were but dim memories, Rooney still maintained the old regimen of evening tea, prayers before breakfast and at bedtime, and Sunday evening hymn singing.

He was very interested in agriculture and was president for some years of the Virginia Agricultural Society. As such he was ex officio a member of the first board of visitors of the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College at Blacksburg in 1872.

Mary Custis Lee’s death came in 1873. Thereafter, the Ravensworth estate in Fairfax County was apportioned among the Lee children. Rooney inherited the mansion with 563 acres. In 1874, he moved to Ravensworth, and lived there until his death. Rooney willed the Ravensworth estate to his widow in trust for their two sons, Robert E. Lee III and Dr. George Bolling Lee. Dr. Lee acquired sole ownership following the death of his brother in 1922. The mansion mysteriously burned in 1925.

Rooney Lee prospered, personally and professionally, but only after surviving hard times and economic disruption. After a halting start, he became a successful farmer, then entered politics. In 1875, he was elected to the Virginia Senate and held that position until 1878. From March 4, 1887, to March 3, 1891, he was a member of the US House of Representatives, where he served until his death.

While serving his second term in the Congress, William Henry Fitzhugh (Rooney) Lee died on October 15, 1891, at the age of 54. Rooney is buried at the Lee Chapel on the campus of Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, near his famous grandfather, father, mother, and siblings.

SOURCES

White House Plantation

Wikipedia: William Henry Fitzhugh Lee