Wife of Declaration of Independence Signer George Read

Gertrude Ross was born in 1733, the daughter of Reverend George Ross, who was for more than half a century a clergyman of Newcastle, Delaware. Gertrude was well educated by her father, beyond the common lot of most girls of her day, even in educated families. It is said, “her person was beautiful, her manners elegant, and her piety exemplary.” She was the sister of George Ross, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and half-sister of John Ross, an eminent lawyer at the Philadelphia bar.

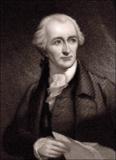

George Read, the son of John and Mary Howell Read, was born in the town of North East, Maryland, on September 18, 1733. His father was a landholder of means, and his mother was the daughter of a Welsh planter. The family moved to New Castle, Delaware, when George was young. He attended school in Chester, Pennsylvania, as well as the Reverend Francis Alison’s Academy at New London, PA.

At the age of fifteen, George began studying law with a Philadelphia attorney. In 1753, he was admitted to the bar, and began his own practice in Philadelphia. Under Delaware law, as the eldest of his father’s six children, he was entitled, to two fifths of his father’s estate. As soon as he came of age, he signed over all his rights in the estate to the younger children, believing that the amount spent on his education was all that he could ask from the estate.

Marriage and Family

On January 11, 1763, George Read married Gertrude Ross Till, the widowed sister of future Signer George Ross, at Emanuel Church, New Castle County, Delaware. There were four children born to the Reads: George Jr., born in 1765, was US District Attorney for Delaware for thirty years, receiving his first appointment from George Washington; William, born in 1767, was Consul-General for Naples at Philadelphia for many years; John, born in 1769, was a prominent member of the Philadelphia bar and Judge of the Superior Court of Pennsylvania; Mary, born 1770, their only daughter.

Gertrude Read seems to have been admirably fitted to be the life companion of the public-spirited and patriotic young man she married. During the Revolution, she was almost constantly separated from her husband because of his service to his country. She suffered considerably, and was often compelled to flee from the British at a moment’s notice. But she was never dejected or complaining; on the contrary, she encouraged her husband in every possible way, not only by word, but by the cheerful manner with which she bore the hardships and burdens.

The enemy was almost constantly a threat from the Delaware Bay, and kept the little colony in a continuous state of alarm. The British army at different periods occupied parts of the colony or went across it, making frequent changes of habitation necessary.

Gertrude was noted for her fondness for horticulture and enjoyed the profusion of flowers, especially tulips, which grew in the extensive garden of their old-fashioned mansion in Newcastle. There she spent most of her life, except for the short periods when she was forced to take her family to Wilmington or Philadelphia during the Revolution.

While in Congress, Mr. Read wrote freely to his wife about public affairs as well as their domestic concerns, and always in the same spirit of delightful comradeship. In 1774, he wrote to her two days before the adjournment of Congress.

1774 letter to Gertrude:

MY DEAR G—-,

I am still uncertain as to the time of my return home. As I expected it, the New England men declined doing any business on Sunday and though we sat until four o’clock this afternoon, I am well persuaded that our business can by no means be left until Wednesday evening and even then very doubtful, so that I have no prospect in being with you till Thursday evening.Five of the Virginia men are gone. The two remaining ones have power to act in their stead. The two objects before us, and what we are to go through tomorrow, are an address to the king and one to the people of Canada. This last was re-committed this evening in order to be remodelled. Your brother George (the Signer) came to Congress this afternoon.

All your friends are well. No news, but the burning of the vessel and tea at Annapolis (the Peggy Stewart), which I take for granted you will have heard before this, comes to hand. We are all well at my lodgings, and send their love to you.

A letter from 1776:

MY DEAR G—-,

I have this morning wrote to Katy Thompson (his sister, wife of General Thompson) proposing to her to send her oldest son George to Philadelphia to the college, where Ned Biddle (another brother-in-law) will provide him with board and lodging, and that she should send her second son to Wilmington, where you will do the like for him. I presume that you will approve of this last.The Province ship left the town yesterday, being hurried off in consequence of intelligence that the Roebuck, man-of-war, was ashore near the cape. A ship fitted out by Congress and called the Reprisal, is ordered down also with several of the gondolas, but a report prevailed last evening that the Roebuck had got off. Little else has been talked of since the Sunday noon that the news came.

I flatter myself that I shall see you on Saturday next. Last Saturday the Congress sat, and I could not be absent. I saw Mr. Bedford last evening: he had a little gout in both feet, attended with a fever: of this last he most complained, but it is gone off. This day is their election for additional members of Assembly. Great strife is expected. Their fixed candidates are not known. One aide talked of Thomas Willing, Andrew Allen, Alexander Wilcox, and Samuel Howell, against independence: the other, Daniel Robertdeau, George Clymer, Mark Kuhl, and the fourth I do not recollect: but it is thought that other persons will be put up.

My love to our little ones, and compliments to all acquaintances.

When the contest between Great Britain and the American Colonies began in 1765, George still held office under the Crown – Attorney General for the Three Lower Counties (the colonial name for Delaware) from 1763 until 1774 – but that did not prevent him from entering actively into every measure to protect the rights of the people.

From that time until his death, he was always in public service – as a member of Congress, a Judge of the Court of Appeals, a United States Senator, and the Chief Justice of Delaware. He protested actively against the Stamp Act, and began a career in the colonial legislature, which lasted more than a decade.

George Read’s Stoneham

In 1754, George moved back to New Castle and started a practice in his hometown. During this period, he lived in town, but maintained Stoneham, a country house near the city – a two-and-a-half story with an L-shaped design. The house was built beginning circa 1730 with what was later the kitchen; the front portion of the house was added before 1769, when George Read bought the property.

Read served in the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1777. Anticipating the Declaration of Independence, the General Assembly of the Lower Counties of Delaware declared its separation from the British government on June 15, 1776. In the Congress, he moved in conservative Patriot circles; he was willing to fight for colonial rights, but was wary of extremism.

Read voted against independence, the only signer of the Declaration to do so, because there was a strong Tory sentiment in Delaware, and he hoped that reconciliation with Great Britain was still possible. But as the debate reached a climax, his mind was changed, and he voted for independence on July 2, 1776, and signed the Declaration of Independence for Delaware.

Once the Declaration of Independence was adopted, the General Assembly called for elections to a Delaware constitutional convention to draft a constitution for the new state. Read was elected to this convention, became its President, and guided the passage of the Thomas McKean-drafted document, which became the Delaware Constitution of 1776.

Read was then elected to the first Legislative Council of the Delaware General Assembly and was selected as the Speaker in both the 1776-77 and 1777-78 sessions. During the fall of 1777, the British captured Delaware President (Governor) John McKinly while Read was in Philadelphia attending Congress. After narrowly escaping capture while returning home, Read became President on October 20, 1777, serving until March 31, 1778.

During these months, the British occupied nearby Philadelphia and were in control of the Delaware River. Read tried, mostly in vain, to recruit additional soldiers and protect the state from raiders from ships in the Delaware River. He oversaw the relocation of the state capital from New Castle to Dover, as a move to protect the capital of Delaware from the British Army.

After Caesar Rodney was elected to replace him as President on March 31, 1778, Read continued to serve in the Legislative Council through the 1778-79 session. After a one-year rest because of ill health, he was elected to the House of Assembly for the 1780-81 and 1781-82 sessions. In 1782, he was appointed Judge of the Court of Appeals in admiralty cases. He returned to the Legislative Council in the 1782-83 session and served through the 1787-88 session.

George Read’s Signature

On the Declaration of Independence

Read was a delagate to the Annapolis Convention held in 1786, a meeting at Annapolis, Maryland, of twelve delegates from five states (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Virginia) that called for a constitutional convention. The formal title of the meeting was a Meeting of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government. The defects that they were to remedy were those barriers that limited trade or commerce between the independent states under the Articles of Confederation.

The commissioners felt that there were not enough states represented to make any substantive agreement. They produced a report which was sent to the Congress and to the states. The report asked support for a broader meeting to be held the next May in Philadelphia, and expressed the hope that more states would be represented and that their delegates would be authorized to examine areas broader than simply commercial trade. The result of the report was the Constitutional Convention held in Philadephia in 1787.

At the Constitutional Convention, Read immediately pushed for a new national government based on a new Constitution. As he put it: “to amend the Articles [of Confederation] was simply putting old cloth on a new garment.” He was a leader in the fight for a strong central government, advocating, at one time, the abolition of the states altogether and the consolidation of the country under one powerful national government. “Let no one fear the states, the people are with us;” he declared to a Convention shocked by this radical proposal.

With no one to support his motion, Read settled for protecting the rights of the small states against the infringements of their larger, more populous neighbors who, he feared, would “probably combine to swallow up the smaller ones by addition, division or impoverishment.” He warned that Delaware “would become at once a cypher in the union” if the principle of equal representation embodied in the New Jersey (small-state) Plan was not adopted and if the method of amendment in the Articles was not retained.

Outspoken, Read threatened to lead the Delaware delegation out of the Convention if the rights of the small states were not specifically guaranteed in the new Constitution. Once those rights were assured, he led the ratification movement in Delaware which, partly as a result of his efforts, became the first state to ratify.

Following the adoption of the Federal Constitution, the General Assembly elected Read as one of Delaware’s first two US Senators. His term began March 4, 1789, he served with the pro-administration majority in the First and Second US Congress, during the administration of George Washington. As Senator, he supported the assumption of state debts, establishment of a national bank, and the imposition of excise taxes.

Given the significant contributions to his country, his good counsel and loyalty to friends, and his principled evaluation and judicious deliberation of the issues of the day, it is quite fitting that George Read was among the crowd gathered on the balcony of Federal Hall in Philadelphia to witness and celebrate George Washington’s inauguration as the first President of the United States of America. Read was a distinguished member of the esteemed fraternity we now refer to as Our Founding Fathers.

Read resigned as Senator on September 18, 1793, to accept an appointment as Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court and served in that capacity until his death.

George Read died on September 21, 1798, at New Castle, Delaware, just three days after his 65th birthday. He was buried there in the Immanuel Episcopal Church Cemetery.

William T. Reid, in his Life and Correspondence, described Read as “tall, slightly and gracefully formed, with pleasing features and lustrous brown eyes. His manners were dignified, bordering upon austerity, but courteous, and at times captivating. He commanded entire confidence, not only from his profound legal knowledge, sound judgment, and impartial decisions, but from his severe integrity and the purity of his private character.” He dressed with great attention to detail, style and elegance, evidenced by the amethyst studded shoe buckles he wore the day he signed the Declaration of Independence.

Gertrude Ross Till Read died on September 2, 1802, at home in New Castle, Delaware.

SOURCES

George Read

George Read, Sr.

Read Family Papers

Gertrude Ross Read

George Read (Signer)

George Read Biography

George Read 1733-1798

George Read: Delaware

America’s Founding Fathers

Delaware’s Third Governor & Colonial Leader