Wife of Confederate General Wade Hampton III

Mary Singleton McDuffie was born on July 7, 1830, in South Carolina. Wade Hampton III, son of Wade II and Ann (Fitzsimmons) Hampton, was born on March 28, 1818, in Charleston, SC, the eldest son of a wealthy and prominent cotton plantation owner. Raised in the aristocratic class, Hampton’s family was one of the richest in the antebellum South. His father taught him how to hunt and fish, and he became an excellent horseman and an expert shot.

General Wade Hampton

Owning as many as 3000 slaves, who worked the family’s enormous holdings, Wade Hampton I was a member of the US House of Representatives, and served as major general during the War of 1812, commanding an American army on the Canadian border. He amassed a huge fortune with plantations in South Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana. When Wade I died in 1835, he left his Revolutionary sword to Wade III.

Wade Hampton II served in the War of 1812 under Andrew Jackson, who chose Hampton to carry the message to Washington of the victory at the Battle of New Orleans. However, Wade II was perhaps best remembered for his domestic activities. He successfully managed the family plantations, and excelled in social and political life. He made the family home, Millwood, almost as much the political capital of South Carolina as was nearby Columbia. He amassed a library of over 10,000 volumes, one of the largest private libraries in the country.

Wade III’s privileged childhood years would be spent on the lavish family estates of Millwood and the family retreat and experimental farm called High Hampton in Cashier’s Valley, North Carolina. He received private instruction and entered the freshman class at South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) at age 14. In 1836, he graduated, and then studied law in order to better handle his business affairs.

Wade’s Aunt Caroline and her husband, Colonel John Preston, returned from Virginia to reside in the Hampton Town House in Columbia, and there began a lifetime relationship between Wade and John Preston. In 1838, Wade married Colonel Preston’s sister Margaret. Of their five children, Wade Hampton IV, Thomas Preston Hampton, Sarah Buchanan Hampton, John Preston Hampton died in infancy, and Harriet Flud Hampton died while still a child.

In 1852, Margaret Hampton died at age 34 of unknown causes.

Wade entered South Carolina politics as a dissenter to the “fire-eating” secessionists that held sway in that most militant Southern state. He was elected to the South Carolina General Assembly in 1852, and served there until 1858, followed by a stint in the South Carolina Senate between 1858 and 1861.

In 1853, Wade II had expanded his holdings in Mississippi and owned 10,000 acres in five plantations. Wade bought three plantations in Mississippi (Wildwood, Bayou Place and Richland). In 1855, he purchased 700 acres in Cashiers, North Carolina.

Wade Hampton married Mary McDuffie on January 27, 1858, at Albemarle Plantation in Richland, SC. They had four children: George McDuffie Hampton, Mary Singleton Hampton, Alfred Hampton, and Catherine Fisher Hampton who died in infancy. Wade began construction of a home for his wife in 1859. Diamond Hill, a large brick Greek Revival style house with a two-room library, was completed in December 1860, not long before the outbreak of the Civil War.

Meanwhile, Wade II had died in 1858, and Wade III inherited Walnut Ridge. He in his turn devoted himself to the management of his plantations in South Carolina and Mississippi. By 1861, his plantations were producing 5,000 bales of cotton a year, each crop worth upwards of a million dollars.

Wade was the epitome of the Southern gentleman: an equestrian, sportsman, and military and political leader. He was in his mid-thirties when the national debate over slavery came to a head in the decade before the Civil War. Wade opposed the institution of slavery (even though he and his family owned more slaves than anyone else in the South). He was against secession and was called a Union Democrat, yet he became a great Confederate leader. South Carolina voted to secede in December 1860 in Charleston.

The Civil War

Although his views were conservative, Hampton was loyal to his home state. During the final debate over secession in South Carolina, he argued against it, but once it became a fact, he put all his former doubts behind him and placed his wealth and his talents at the service of the Confederacy. He allowed his cotton crop to be used as collateral for government credit.

He resigned from the Senate, and was made Colonel by President Jefferson Davis on June 12, 1861, though he had no military experience, and received permission from Davis to raise a small private army, or legion. He clothed and equipped his force, called Hampton’s Legion – six companies of infantry, four companies of cavalry, and one battery of artillery equipped with six field guns – entirely out of his own pocket. Wade’s sons, Wade IV and Preston, were privates in the Legion.

He enlisted some of the best young men in the state to fill its roster, and its officers were recruited from the elite. Every step of its organization was reported in the newspapers. Their arrival in Richmond in the first weeks of the rebellion was publicly hailed. On July 4, 1861, he was attached to General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army.

Older than the other officers in the Confederate cavalry, Hampton was the antithesis of the banjo-serenaded “gay cavaliers” who were his peers. For Hampton, war was not a frolic or glorious adventure but a grim business, to be discharged as efficiently as possible and without relish. He conducted his affairs with a courteous reserve befitting the gentleman he was.

Despite his lack of military experience and his relatively advanced age of 42, Hampton was a natural cavalryman – brave, audacious, and a superb horseman. He merely lacked some of the flamboyance of his contemporaries, such as his eventual commander, J.E.B. Stuart, age 30. Wade was one of only two officers (the other being Nathan Bedford Forrest) to achieve the rank of lieutenant general in the Confederate cavalry service.

In his prime, Hampton was a big man. He stood six feet tall with the build of an athlete, and possessed great moral, physical, and political courage. His strength and endurance became legendary. Instead of a regular officer’s sword or a cavalry saber, he carried a huge double-edged straight sword that was all of 45 inches long.

General Hampton Equestrian Statue

South Carolina State House in Columbia

On July 21, 1861, at the Battle of First Manassas, Wade Hampton deployed his Legion at a decisive moment, giving the brigade of Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson time to reach the field. Wade was wounded while he led a charge against a federal artillery position, when a bullet grazed his scalp, but he had the wound bandaged and resumed command. Without any military training or experience, Wade had shown personal courage in his first time under fire, and an instinctive ability to lead men and read terrain.

Over the next few months, by his professionalism and zeal in recruiting, Wade won the personal friendship of army commander General Joe Johnston, who put him in command of a full brigade of cavalry in January 1862 and recommended him for promotion. When he led his brigade during the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, Wade won praise for “conspicuous gallantry” in an early skirmish, and another recommendation for promotion, citing his “high merit.” He was appointed brigadier general on May 23, 1862, while commanding a brigade in Stonewall Jackson’s division in the Army of Northern Virginia.

At the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, Wade was severely wounded in the foot, but refused to leave the field. He remained on his horse, under heavy fire, while a surgeon extracted a musket ball from his foot. His boot was put on his wounded foot and he returned to battle. The next day the boot had to be cut off because his foot was so swollen and inflamed. He was sent home to Columbia on crutches but returned in less than a month.

After the Peninsula Campaign, General Robert E. Lee reorganized his cavalry forces as a division under the command of General J.E.B. Stuart, who selected Hampton as his senior Brigadier, to command one of two cavalry brigades. In December 1862, around the time of the Battle of Fredericksburg, Wade led a series of three successful winter cavalry raids behind enemy lines, capturing numerous prisoners and supplies without suffering any casualties, earning a commendation from General Lee.

Since Wade and his brigade were south of the James River recruiting during the Chancellorsville campaign, December’s raids stood as the last time he had been engaged, as the Gettysburg Campaign got underway in the early summer of 1863. His reputation by that time rivaled that of his superior, Jeb Stuart, and he had become a valuable officer to General Robert E. Lee.

Wade was one of the great finds among the officers corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. By the summer of 1863, he had been in command of his cavalry brigade for about a year, and had led it with unexcelled success. His only shortcoming was a tendency to neglect his mounts.

On the evening of June 8, 1863, almost the entire Calvary of the Army of Northern Virginia – five full brigades – were camped on the west bank of the Rappahannock River. The following morning, they were surprised by the full force of the Calvary of the Army of the Potomac, which had crossed to meet them at dawn.

On June 9, during the Battle of Brandy Station – the war’s largest cavalry engagement – Wade is credited with leading one of the most gallant Calvary charges of the battle. His actions might have resulted in the capture of the whole Union force on the field, had not his advance been checked by heavy Confederate artillery fire well-directed at the head of his charge. It was also at that battle that Wade lost his brother Lt. Colonel Frank Hampton to enemy fire.

Wade’s brigade then participated in Jeb Stuart’s wild ride to the northeast, swinging around the Union army and losing contact with General Lee. When the fighting began at Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, Wade was still with Jeb Stuart, in Dover, Pennsylvania, 23 miles northeast of the battlefield. All the cavalrymen were numb with lack of sleep after three solid days in the saddle since crossing the Potomac. But after a short rest in Dover, the division pushed on toward Carlisle in search of provisions, with Wade’s tired troopers at the rear of the column.

Halting in Dillsburg with the captured wagons and prisoners from the raid, Wade received word from Stuart before daybreak on July 2 that the army had been found at Gettysburg, and Wade headed south that morning. By 2:00 pm, his brigade had halted a few miles northeast of Gettysburg.

Stuart and Hampton reached the vicinity of Gettysburg late on July 2, 1863. Waiting on his horse beside the road, Wade was confronted by a Union cavalryman pointing a rifle at him from 200 yards away. Wade charged the trooper before he could fire his rifle, and became involved in a strange duel with the blue trooper at close range. At one point, he chivalrously stopped to let the Yankee clean his gun before resuming the fight.

Wade at last wounded his assailant in the wrist, but just then another Union soldier, wielding a sword, rushed forward and blind-sided Wade with a saber cut to the back of the head. The general’s hat and thick hair saved him from a fatal wound. He returned to his brigade with a bloody four-inch gash on his scalp, as well as a shallow chest wound.

On the morning of July 3, General Hampton and his men rode two miles out of Gettysburg on the York Pike, then turned south with Stuart’s other cavalry brigades. Their goal was to get in the rear of the Union army after the end of a Confederate cannonade, which would signal the beginning of the main Confederate attack against Cemetery Ridge – Pickett’s Charge.

At 3 o’clock that afternoon, the artillery went silent, but in their attempt to disrupt the Union rear, the Rebels collided with Yankee cavalry. In the swirling, hand-to-hand melee that ensued, Wade received two more saber cuts to his head, one of which opened the prior injury and left a long gaping wound. But the gash was plastered shut and he remained with his men.

Wade continued fighting until a piece of shrapnel penetrated his right hip, and he was unable to ride. He was carried back to Virginia in the same ambulance with General John Bell Hood.

In September 1863, while Wade convalesced, the cavalry was reorganized. General Lee made Wade a major general and placed him at the head of one of two cavalry divisions, with General Fitzhugh Lee in command of the other. Wade’s hip wound was slow in healing, and he took a full four months to recover, and was unable to return until November 1863.

Charge at Trevilian Station

Mort Kunstler, Artist

In early June 1864, General Philip Sheridan led 6000 Federal cavalrymen on a mission to destroy a vital section of the Virginia Central Railroad. On the morning of June 11, Hampton and 5000 Confederate cavalrymen intercepted Sheridan’s force at Trevilian Station in Virginia. The next day, the outcome was decided when a bold Confederate counterattack shattered the Federal line. On June 13th, Sheridan and his troops retreated without destroying the railroad.

In the spring of 1864, General Ulysses S. Grant began his Overland Campaign, determined to bring the war to an end. At the Battle of Yellow Tavern on May 11, 1864, J.E.B. Stuart was killed. A month later, at the bloody Battle of Trevilian Station, Wade commanded 5,000 cavalrymen in a gallant charge to ward off a raid by Union General Philip Sheridan’s cavalry of 6,000 men.

Wade was appointed Chief of Cavalry on August 11, 1864, commanding all of the cavalry in the Army of Northern Virginia. He lost no cavalry battles for the remainder of the war. At the siege of Petersburg a month later, Wade was pinned down with the Army of Northern Virginia, which was gravely short of supplies.

At 1 am one morning, with 4,000 Cavalrymen, Wade rode out to raid a poorly guarded federal encampment and pulled off the largest cattle rustle in history, which became known as the Beefsteak Raid. He captured 300 prisoners and 2,486 head of cattle, and drove them back to feed the starving Confederates.

Burgess Mill

In October 1864, during the Siege of Petersburg, before the winter weather shut down active operations for the season, General Grant made another Union effort to cut the remaining Confederate supply routes. “I think it cannot be long now before the tug will come which, if it does not secure the prize, will put us where the end will be in sight,” Grant told his wife Julia in mid-October. This plan came from General Meade, who was anxious to silence several Northern newspapers critical of his leadership.

Directed by USA General Winfield Scott Hancock, divisions from three Union corps (II, V, and IX) and Gregg’s cavalry division, numbering more than 30,000 men, withdrew from the Petersburg lines and marched west to operate against the Boydton Plank Road and South Side Railroad. The initial Union advance on October 27 gained the Boydton Plank Road shortly after 10:30 am, a major campaign objective.

Hancock’s only opposition had come from Wade Hampton’s cavalry, but now confronting him at Burgess’ Mill was a line of infantry and artillery posted across Hatcher’s Run and covering the Boydton Plank Road bridge. Every passing second meant more defenders were on their way from Petersburg. According to the original plan, Warren was to support Hancock, but his route led him into a nearly impenetrable underbrush. In a very short time his units became lost, confused, and unavailable to Hancock.

At about 1:30 pm, while Hancock was preparing for the next phase of his advance, Grant, Meade, and their staffs arrived. Grant undertook a personal reconnaissance of the enemy’s line behind Hatcher’s Run and concluded that a breakthrough would not be possible. Still hoping to punish the Rebels, Grant issued instructions for Hancock to hold his position until noon the next day “in hope of inviting an attack.” Grant and Meade left Hancock around 4:00 pm.

Thirty minutes later, the Confederates attacked from three directions near Burgess’ Mill. Some of Hampton’s cavalry pushed east along the White Oak Road while another portion of it came up Boydton Plank Road from the south, pressing Hancock’s rear guard. A force of Confederate infantry led by General William Mahone swept down across Hatcher’s Run and flanked one Union brigade. Hancock’s men stood their ground and beat off each attack, though they paid a heavy price for doing so, losing nearly 1,800 men.

At one point, Wade had sent his son Preston, a lieutenant and his father’s aide, to deliver a message. A while later, Wade and his other son, Wade IV, rode in the same direction. Before traveling 200 yards, they came across Preston’s body, and Wade IV was shot in the back as he leaned over his brother.

The younger son would survive, but Preston Hampton died from his wound. Wade carried his dead son from the battlefield; never again would this grieving father allow any of his children to serve with him.

While Lee’s army was bottled up in the Siege of Petersburg in January 1865, Wade was detached from the Army of Northern Virginia to find new mounts for the battered Confederate cavalry. He was promoted to Lieutenant General on Feb 14, 1865.

Hampton’s home was destroyed when General Sherman’s Federal troops burned much of Columbia on February 17, 1865. Wade’s young son Alfred was there and later remembered the scattering of the corner brick pillars, and the mass of crushed bricks that were all that remained of his family’s home.

On February 24, Wade took command of General Joseph E. Johnston’s cavalry, about 4,000 men, and did what he could to arrest the advance of USA General William Tecumseh Sherman’s march northward from Savannah through the Carolinas in the late winter of 1865.

On April 16, General Johnston met with General Sherman at Durham to negotiate terms of surrender, and Wade was in attendance. On April 26, 1865, General Wade Hampton surrendered to General Sherman along with General Johnston’s Army of Tennessee at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina, after rising higher than any other amateur soldier in the Confederacy.

Postbellum Life

After the war, Wade returned to Columbia and found his homes and estates in ruins. He did not rebuild Diamond Hill, but instead used the bricks to construct a modest cottage that he called Southern Cross on the Diamond Hill property. Much of Wade’s fortune had been depleted supplying his soldiers, and his many slaves had been freed by the Union Army. He engaged in cotton planting, but was not successful. He filed for bankruptcy in 1868.

Wade accepted from the first all the legitimate consequences of defeat, an entire submission to the law, and the civil and political equality of the former slaves; but he steadily defended the motives and conduct of his people and their leaders. He encouraged Southerners to accept their defeat graciously, and set an example for better race relations by constructing a school and a church for emancipated slaves. He said: “As a slave, he was faithful to us; as a free man, let us treat him as a friend. Deal with him frankly, justly, kindly.”

Wade was offered the nomination of governor in 1865, but refused because he felt that those in the North would be suspicious of a former Confederate General seeking political office only months after the end of the War. Despite his refusal, Hampton had to campaign for his supporters not to vote for him in the election.

1867 saw the beginning of Reconstruction, which was characterized by eight years of turmoil and corruption. The South was divided into military districts and the state governments were liquidated. Wade’s conciliatory policy toward the ex-slaves found little favor for some time. He spent the Reconstruction period on his Mississippi plantations. Efforts there to rebuild his fortune failed, and the general was forced into bankruptcy by 1868.

In 1869, Wade founded the Southern Life Insurance Company in Atlanta, along with General John B. Gordon and Benjamin H. Hill. Jefferson Davis became the president of the company.

Mary McDuffie Hampton died on March 1, 1874, at Charlottesville, Virginia, a serious blow to her husband.

South Carolina Governor

Wade became a leader in opposing the Republican regime in South Carolina, and emerged as the leader of the so-called Bourbons. He ran for governor of South Carolina against the incumbent, Daniel Chamberlain, a Maine carpetbagger (a Northerner seeking private gain under Reconstruction). Foes of Radical Reconstruction in South Carolina saw the general as the perfect conservative choice for the governorship in the tumultuous election of 1876. A sad factor in his seeking public office was that he needed the income these positions generated.

The vote was very close, and both parties claimed victory. For over six months, there were two legislatures in the state, both claiming to be authentic. Eventually, the South Carolina Supreme Court ruled Hampton as the winner of the election by 1,100 votes.

The election of the first Democrat in South Carolina since the end of the Civil War, as well as the national election of Rutherford B. Hayes as President, signified the end of the long period of Reconstruction in the South.

The incumbent Governor Chamberlain refused to vacate the State House. Finally, after four months, President Hayes intervened. Chamberlain was forced to leave, and Federal troops were withdrawn at last in April 1877, and Wade finally began his two-year term in office.

As Governor, Wade’s top aides included M.C. Butler, Johnson Hagood, and Joseph Kershaw – all had been Confederate generals. Wade attributed his victory to 17,000 Negro voters, and as promised, appointed over 80 blacks to office. He supported black suffrage, and his administration was characterized by honesty and fiscal conservatism. He worked hard to live up to his pledges of equal treatment for both races, but even the respected Hampton was unable to stem the tide of those who wanted total disenfranchisement and segregation at any cost.

On November 6, 1878, Wade won re-election as governor easily. The next day, he went on a deer hunt, where he fell and sustained a compound fracture of his right leg. He developed an infection, severe pain, and a high fever; he was sick for some time, and an amputation below the knee was required one month later.

Despite refusing to announce his candidacy, Hampton was elected to the United States Senate by the South Carolina General Assembly, on the same day his leg was amputated, to take office in March 1879. He served there for thirteen years.

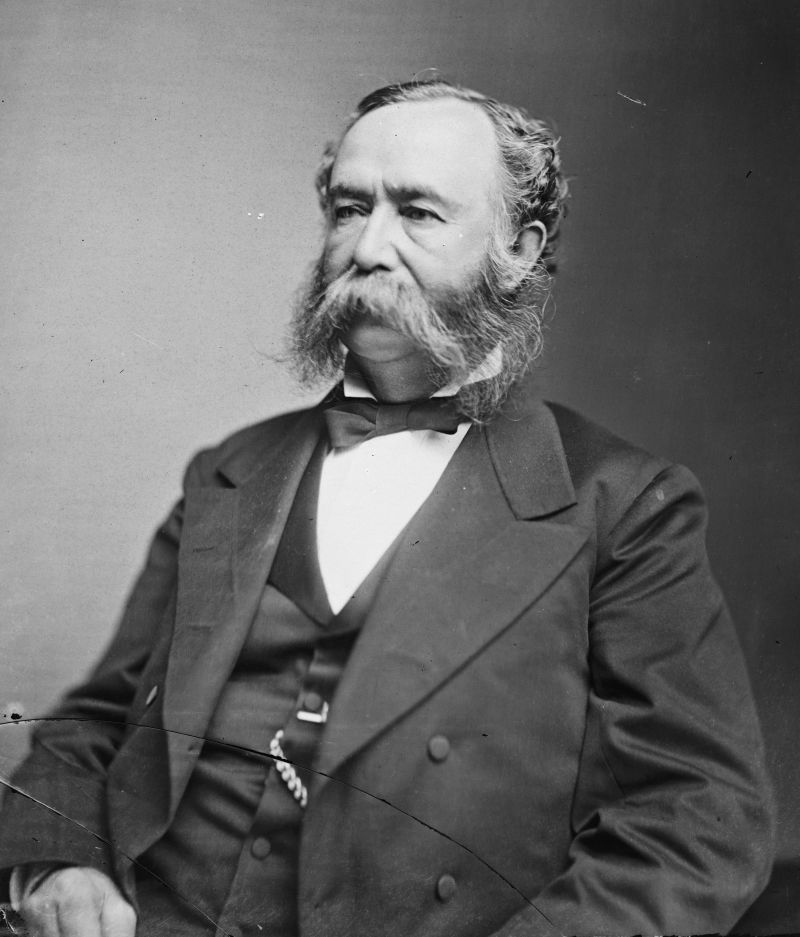

Senator Wade Hampton III

While in the Senate, Hampton found his political influence waning, and with the election of Pitchfork Ben Tillman as Governor in 1890, Wade’s influence dwindled even further. Tillman engineered Wade’s defeat for another term in the Senate in 1890. Wade was all but destitute after the election, and his political influence was at an end.

In 1893, Wade was appointed United States Railroad Commissioner by President Grover Cleveland, a position Wade held until 1897. He went on a transcontinental trip in a private railroad car, and later became the director of two railroads.

In 1899, Southern Cross and the house at Millwood were burned by arsonists. Only Wade’s Civil War swords and silver were saved. An elderly man, he had limited funds and limited means to find a new home. Over his strong protests, the people of Columbia raised funds throughout the state to build a residence for him at the corner of Barnwell and Senate streets.

In 1901, Wade became increasingly ill, and Dr. Watt Taylor diagnosed a “heart condition complicated by old age.” His children and his sisters gathered at his bedside, and he spoke his final words, “God bless all my people, black and white.” He was the most revered man in the history of South Carolina, and yet he died an old man in near poverty.

General Wade Hampton III died on April 11, 1902, at the age of 84, exactly 25 years to the day after he became governor. More than 20,000 people lined the streets at his funeral, said to be the largest in South Carolina. He is buried Trinity Cathedral Churchyard in Columbia,

Wade left his real estate in South Carolina to his daughter Daisy, who had been his caretaker. Son McDuffie received three silver racing cups, and the remainder of his silver was divided among the three children.

Five columns still stand at Millwood. Now crumbled and covered with vines, they serve as a ghostly reminder of those towering figures in South Carolina history, the three Wade Hamptons.

SOURCES

Burgess Mill

Hampton Legion

Wade Hampton III

The Hampton Family

General Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton 1818 – 1902

Journal of Southern History

Wade Hampton III Biography

Wikipedia: Wade Hampton III

The Generals of Gettysburg: The Leaders of America’s Greatest Battle by Larry Tagg. Brigadier General Wade Hampton

South Carolina Governors – Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III: The Statue Behind the State House