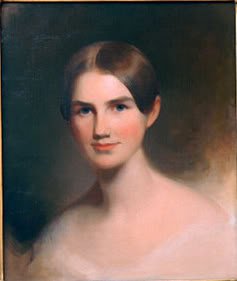

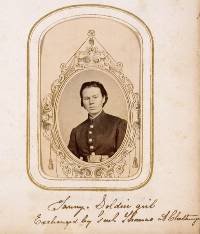

Wife of Union General and Senator Francis P. Blair, Jr.

Francis Preston Blair, Jr. was born on February 19, 1821, in Lexington, Kentucky, into a prominent political family. His parents were Eliza Gist Blair and Francis Preston Blair Sr., who was a member of President Andrew Jackson’s Kitchen Cabinet and advisor to several presidents. Young Frank was raised in Kentucky until nine years of age (1830), when the family moved to Washington, DC, where his father had been invited to edit The Congressional Globe.

Apolline Alexander Blair

Trained by his father for a public career, Frank Blair attended schools in Washington, DC. He was a bright but difficult student, who was expelled from several private schools. As a college student, he was expelled from the University of North Carolina and Yale for misconduct. His father then sent him to Princeton, where Frank managed to complete his studies in 1841, but he was denied graduation for participating in a wild party in his final week. He finally received his degree a year later, at the age of twenty.

After graduation at Princeton, Frank returned to Kentucky, and studied law under Lewis Marshall, an eminent lawyer and brother of Chief Justice John Marshall, one of the most distinguished jurists of our country. He attended law school at his father’s alma mater, Transylvania University, where he continued until he completed his legal studies.

When Frank visited St. Louis to see his brother, Montgomery, he decided to make it his home. After passing the bar, he joined Montgomery’s law firm in St. Louis in 1843. Montgomery prospered in politics and later served as Abraham Lincoln’s Postmaster General.

In 1845, Frank was advised by his physician to change his living habits, and he made a trip West in the company of some traders and trappers. At the beginning of the Mexican-American War in 1846, Frank enlisted in the US Army and served under General Philip Kearney. Blair was then appointed Attorney General for the New Mexican Territory. Believing “Indians and Mexicans… a lying thieving, treacherous, cowardly, bragging, and depraved race of people,” Blair provoked fights with Santa Fe residents, and secured death sentences for fifteen Mexican civilians who battled the military government.

At the end of the Mexican-American War, Blair returned to St. Louis in 1847 to resume his law practice and briefly edited the Missouri Democrat.

On September 8, 1847, Frank Blair married Apolline Alexander, daughter of Andrew Alexander of Woodford County, Kentucky, and they had eight children.

In 1848, Mr. Blair, following in the political footprints of his father, advocated the tenets of the Free Soil Party, which was comprised of former antislavery members of the Whig and Democratic Parties. This political group opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories, and worked to remove existing laws discriminating against freed blacks in states such as Ohio. They argued that free men on free soil was a morally and economically superior system to slavery. The Free Soilers membership was largely absorbed by the Republican Party in 1854.

Blair was a slaveowner, but opposed the expansion of slavery into the American West and favored the colonization of blacks in Africa. In 1848, Blair helped to found the Free Soil party in Missouri and edited the party’s paper, the Barnburner. He became the acknowledged leader of that party, not only in the state of Missouri, but in the Union. His energetic condemnation of slavery and its expansion provoked an assassination attempt on his life.

Blair did endorse, however, the Compromise of 1850, which allowed the electorates in the Utah and New Mexico territories to vote on the slavery issue, and let California enter the Union as a free state. His stance on the 1850 Compromise led to a break with his political mentor, Senator Thomas Hart Benton.

In 1852, Blair was elected to the Missouri Legislature, and was re-elected for a second year. In 1856, Blair used family friend, Thomas Hart Benton, to promote his election from a St. Louis district to the US House of Representatives. While in the House of Representatives, Blair fearlessly advocated his doctrines, contending against slavery in the territories. He supported the gradual abolition of slavery in the Union, and the colonization of the slaves in Central America. Frank Blair’s maiden speech on the House floor, partly written by his father, depicted slavery as a national problem, rather than as a regional institution.

In 1859, Blair gained national recognition for an antislavery speech (another collaboration with his father), in which the Congressman articulated his plan of gradual emancipation, colonization, and free labor. The oration was published as The Destiny of the Races on This Continent. He was defeated in 1858 but re-elected in 1860.

In 1860, Blair became a Republican and after endorsing Missouri’s Edward Bates for the presidential nomination, switched at the national convention and backed Abraham Lincoln. Blair campaigned vigorously for Lincoln in the general election, and was himself elected by a narrow margin to Congress as a Republican. The Republicans formalized the split within the Democratic party over slavery and helped push both sides toward the sectional extremes of 1860-61.

The Civil War

When the Southern states seceded and the threat of civil war mounted, Blair personally financed the organization of paramilitary units (called Home Guards) to defend St. Louis and Missouri for the Union. Blair, believing that the southern leaders were planning to carry neutral Missouri into the movement, began active efforts to prevent it. When hostilities became inevitable, acting in conjunction with Captain (later General) Nathaniel Lyon, he suddenly transferred the arms in the Federal arsenal at St. Louis to Alton, Illinois.

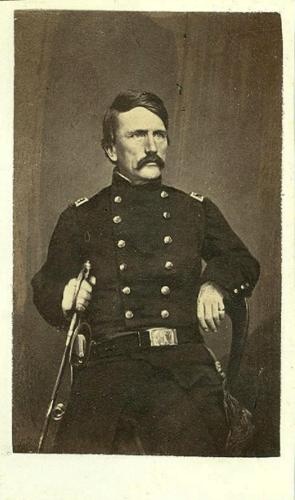

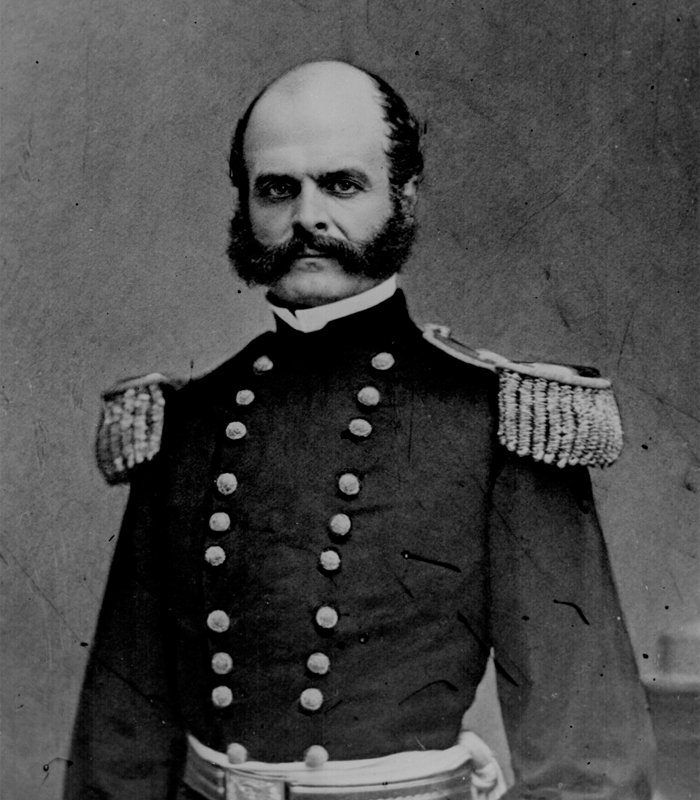

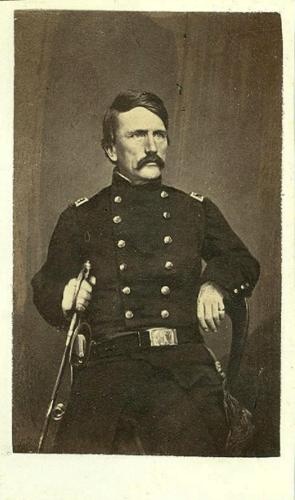

Francis Preston Blair, Jr.

When war broke out, the slavery issue fractured Missouri Republicans and pushed Blair to promote Lincoln’s policy of quick reconciliation. Blair’s distance from the radical wing of the Republican party manifested itself in his efforts to remove John C. Fremont from command of the Department of the West. Fremont offended Blair by opposing the latter’s patronage recommendations and by supporting immediate emancipation. The battle became personal when Fremont’s wife, Jessie, traveled to Washington to lobby for Blair’s arrest. Ultimately, Blair ousted Fremont from office on grounds of corruption and ineffectiveness.

In his 1850s electoral victories, Blair had relied on votes from St. Louis’ large German immigrant population, which included 1848 political refugees like Carl Schurz. After 1861, German liberals pressed for stronger measures against Confederates and sought progress on black liberty. Fremont’s fall angered Germans who favored his stand on emancipation and benefited from his distribution of patronage.

Blair narrowly won re-election in 1862 amid charges of fraud. Worried about personal debt, his eroding political base, and the need to a gain a military reputation, Blair resigned from Congress to take a commission in the Union army. He returned to Missouri, where he used his own money to raise seven infantry regiments during the summer of 1862, and was commissioned a Union brigadier general on August 7, 1862.

By November 1862, Blair was leading a division in the Yazoo Expedition, and earning plaudits from Major General William Tecumseh Sherman for his leadership at Chickasaw Bluffs in late December 1862. Military service gave Blair a veteran’s credentials and allowed him to forge a political friendship with General Sherman.

Blair secured a commission as a major general and commanded Missouri troops in the Vicksburg Campaign. He was commanding a division on the Union line north of Vicksburg, Mississippi, when CSA Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton surrendered the city to Major General Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, 1863. After the siege of Vicksburg, Blair was promoted to the rank of major general.

In the fighting around Chattanooga in the fall of 1863, Blair led the XV Corps, and during Sherman’s drive toward Atlanta, Blair commanded the XVII Corps in bloody fighting. As a soldier, he was a distinguished divisional and corps commander during the Atlanta campaign. After the fall of Atlanta, Blair led his corps in the March to the Sea in November and December 1864.

Blair was one of General Sherman’s corps commanders in the final campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas. He was in Goldsboro, North Carolina, when word came that General Robert E. Lee had surrendered. Both Generals Grant and Sherman, highly critical of most political generals, rated Blair one of the most competent military leaders of the war.

At the close of the war, Blair, having spent much of his private fortune in support of the Union, was financially ruined. Blair was re-elected to Congress as a Republican, he backed the more lenient Reconstruction plans proposed by President Lincoln and, after Lincoln’s assassination, by President Andrew Johnson, while he fought strenuously against the policies of the Radical Republicans. He so embittered his congressional colleagues that they rejected President Johnson’s nominations of him as revenue collector in St. Louis and as U.S. minister to Austria.

During Reconstruction, Blair’s differences with radical Republicans resulted in his return to the Democratic Party. Blair and his family objected to radical measures like the ironclad loyalty oath, and took personal offense at radical opposition to the administrations of Lincoln and Johnson, both of whom were family friends. Blair deepened partisan divisions with such hyperbolic criticism of Reconstruction as “Negro domination” and “unconstitutional.” In 1867, Blair invested in a southern plantation. The business failed, and Blair attributed some of the problems to radical policies, and what he perceived as black indolence.

Defeated by the Republicans for the Senate in 1867, Blair sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1868. The Democrats chose ex-New York governor Horatio Seymour as their candidate, but nominated Blair as Vice President. During the campaign, Blair advocated nullification of the Reconstruction Acts and predicted that if General Ulysses S. Grant, the Republican presidential nominee, were elected, his presidency would degenerate into a military dictatorship. Blair’s harsh words and abrasive personality alienated potential supporters and provided fodder for his Republican opponents.

Ulysses S. Grant trounced Seymour and became the new president, the election and Blair’s role in it, shaped the Democrats’ new strategy of accepting the South’s defeat and attacking Republican corruption, a tact that appealed to liberal Republicans and helped undo the radical program.

Blair had an odd minor notoriety, when on July 29, 1870, he was an accidental witness to an incident in a famous homicide case. Staying at the then famous Fifth Avenue Hotel, Blair woke up to cries of help from across the street, and watched from his hotel window as two men ran out of a brownstone mansion across the street. They were sons of Benjamin Nathan, the Vice President of the New York Stock Exchange, who had been bludgeoned to death the previous night. There was a series of hearings, and even suspicion towards several people, but the mystery was never solved.

A smoker and heavy drinker, Blair suffered from migraine headaches, and a stroke in 1872 further deteriorated his health. On November 16, 1872, he was stricken with paralysis on his right side, from which he never recovered. Blair learned to write with his left hand and continued his political efforts. He was defeated for re-election to the Senate in January 1873.

Francis Preston Blair, Jr. died of head injuries sustained in a fall on July 9, 1875, at St. Louis, Missouri. He was buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery there.

Apolline Alexander Blair, widow of Francis P. Blair, was the organizer and first president of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Board of Managers. In the winter of 1878, she gathered a group of 20 prominent women to discuss the plight of poor, sick children. Having lost two children to infectious illness, Blair was especially aware of the need for hospital care for children.

Though there were established hospitals to care for the poor, children were excluded because the hospitals lacked the staff and facilities to care for them. Blair proposed to her friends that they begin a fund drive to establish a children’s hospital to provide medical and nursing care for needy children. They organized themselves into a Board of Managers and raised $4,500 to purchase a building at 2834 Franklin Avenue.

The certificate of incorporation that was filed on May 6, 1879, listed only women: Apolline Blair, Mary W. McKittrick, Caroline B. Treat, Margaret H. DeWolf, Rebecca Webb, Cherrell W. Parker, Virginia E. Stevenson, and M. Louise Norris. The hospital opened on October 29, 1879, and Blair led the Board of Managers until 1883. She continued to serve on the Board, often as an officer, until her death.

Appoline Alexander Blair died in 1908 at the age of 80.

Apolline and Francis Blair, Jr. Gravesite

Bellefontaine Cemetery

St. Louis, Missouri

SOURCES

This Day in History

Francis Preston Blair

Francis Preston Blair Jr.

Apolline Alexander Blair

Hon. Francis P. Blair, Jr.

Index to Politicians: Blair

Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative

Wikipedia: Francis Preston Blair, Jr.

Most of this column is about Francis Preston Blair and not his wife. She’s at the bottom. Maybe remove him and just focus on her.