| Steele gives Greene two bags of coins |

Patriot of the Revolutionary War

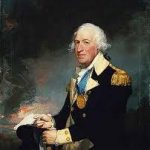

After the Battle of Cowpens, South Carolina (January 17, 1781), Patriot General Nathanael Greene was trying to gather and equip his scattered army to attack and defeat British general Charles Cornwallis. General Greene had ridden alone toward Salisbury, North Carolina and arrived at an inn late at night, declaring to a friend there that he was “fatigued, hungry, alone and penniless!” Innkeeper Elizabeth Steele overheard his comment.

After serving the general a hearty meal, Elizabeth Steele gave the general two bags of gold and silver, perhaps her earnings of years. With Steele’s help, Greene went on to unravel British control of the South, while leading Cornwallis toward Yorktown, Virginia, where Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781. This surrender eventually led the British government to negotiate an end to the Revolutionary War, resulting in independence for the new United States.

Elizabeth Maxwell was born in 1733. She was a member of the great Scottish family of Maxwells who came to Rowan County, North Carolina in that mass migration of German, English and Highland Scotch colonists through the Valley of Virginia and into the Piedmont region of North Carolina from Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and northeast Virginia.

Elizabeth’s first husband was Robert Gillespie, who established a tavern to support his family. From her marriage to Robert, there were two children: Robert Jr. and Margaret. Robert Sr. was murdered and scalped by Indians in 1763.

Elizabeth then married William Steele, and they continued to maintain the tavern, which was a famous resort for the prominent men of that day. William Steele was a Commissioner of Salisbury, North Carolina. He died November 1, 1773, at thirty-nine years of age.

America’s War for Independence moved into the South in full force in May 1780, when the British occupied Charleston. The British Navy returned north, leaving the army under the command of General Charles Cornwallis. Cornwallis moved northward through South Carolina, and won a decisive victory at Camden in August. But as he entered North Carolina in October, his forces met a significant defeat at Kings Mountain, and he retreated south again.

The American forces looked to an unlikely new leader, a Quaker from Rhode Island – General Nathanael Greene – who assumed command of the Southern Army December 2, 1780. The army was weak and badly equipped and was opposed by a superior force under Cornwallis. Greene sent General Daniel Morgan to lead a force against the brash and cocky British Colonel Banastre “Bloody” Tarleton and Morgan defeated Tarleton in a virtual ambush at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, where nearly nine-tenths of the entire British force were killed or captured. This was a decisive event in the Revolutionary War.

The Carolinas were a tangle of wide fast rivers, swampy areas, and heavily wooded. Bridges were rare and most river crossings were made at fords; even then, crossings were dependent on the depth and flow of the water. Roads were for the most part merely wagon tracks. On winter days they were a quagmire of mud, in which a wagon could sink to the hub. Nights were a nightmare of frozen ruts for American soldiers on night marches.

After the Battle of Cowpens, the two armies raced for the river crossings, as Greene led Cornwallis across the heart of North Carolina and away from his base of supply in Charleston. At Ramseur’s Mill, Cornwallis destroyed most of his wagons and baggage and equipped his army as light infantry for ease of movement. The two forces next exchanged fire across the fords of the Catawba River north of the town of Charlotte.

With only a small escort, General Greene had left his main force at Hick’s Creek [SC] and joined General Morgan at Oliphant’s Mill near Sherrill’s Ford on the Catawba River. From there, Greene sent for his army, and hoped to reunite his forces at Salisbury and face Cornwallis there. Morgan and his light infantry headed from Beattie’s Ford toward Salisbury on January 31.

On February 1, when General Morgan learned that Cornwallis had crossed the river at Cowan’s Ford, he and his 1800 men began their retreat eastward toward the Yadkin River. They marched through the town of Salisbury, North Carolina, and camped about half a mile east of the town in a grove. His men were poorly supplied: some wore little more than loincloths, and the bare feet of many left bloody footprints in the red clay. According to Lt. Thomas Anderson’s journal, the march was difficult, “every step up to our Knees in Mud it raining On us all the Way.”

General Nathanael Greene remained near the Catawba, and made arrangements to meet the militia on the road to the town of Salisbury, but the militia never arrived. After midnight a messenger finally arrived with the news. The militia had taken a toll on the British soldiers crossing at Cowan’s Ford that day, but the loss of their commander, General William Lee Davidson, had dispirited the troops. Cornwallis had managed to cross the Catawba, and the Patriots were hotly pressed by the British.

Greene also learned that British Colonel Tarleton’s Dragoons had launched a surprise attack on Davidson’s remaining forces, killing between 10 and 50 men, and the battle-weary militia were scattered. Tarleton’s men had found a circular written by Nathanael Greene, imploring the local militia to join his forces:

Let me conjure you, my countrymen, to fly to arms and repair to Head Quarters without loss of time, and bring with you ten days provision. You have everything that is dear and valuable at stake; if you will not face the approaching danger your Country is inevitably lost. On the contrary if you repair to arms and confine yourselves to the duties of the field, Lord Cornwallis must certainly be ruined. The Continental Army is marching with all possible dispatch from Pee Dee [SC] to this place. But without your aid their arrival will be of no consequence.

The militiamen who had responded to Greene’s flier by mustering at Torrance Tavern were dead; with Cornwallis’ troops rolling steadily through the countryside, few more would turn out to help Greene’s little army. Greene’s aides had been dispatched to different parts of the retreating army, while a disheartened Greene rode alone to Salisbury.

Salisbury in 1781 was a small frontier town that served as the military headquarters for western North Carolina. A laboratory there produced cartridges, and could have made other military supplies; a shoe factory was also located here. Cloth was given to the women of the area, who sewed it into garments and were paid in salt.

Greene arrived at Steele’s Tavern in Salisbury early on the morning February 2, without the militia he had hoped to rendezvous with, feeling the loss of General Davidson, and disappointed that his main army had not yet arrived. He was greeted there by his army physician, Dr. Joseph Read. Startled by the general’s appearance, the doctor inquired about his well-being. “Fatigued, hungry, alone, and penniless!” was the General’s reply.

Elizabeth Steele, the mistress of the tavern – which also served as an inn for travelers – overheard his remark. She saw first to Greene’s hunger with a comfortable breakfast. He had hardly taken his seat at the well-spread table, when Mrs. Steele entered the room, and carefully closed the door behind her. Approaching her guest, she reminded him of the despondent words he had uttered, which implied that he did not trust the devotion of the colonists to the cause of freedom.

“Take these,” she said, “for you will need them, and I can do without them.” She withdrew from under her apron two small bags full of specie (coins, as opposed to paper money), probably her savings of years. General Greene was so grateful for Mrs. Steele’s support of the fight for independence that he took down a colored engraving of King George III and Queen Charlotte hanging on the wall. With a piece of charcoal, he wrote on the back of it, “O, George, hide thy face and mourn.” Then he replaced the picture with the face to the wall.

Greene’s circumstances improved greatly while in Salisbury. In addition to Elizabeth’s aid, he discovered a collection of more than 1700 Continental arms stashed away for the militia. General Greene spent the remainder of February 2nd and 3rd moving his men, the Salisbury supplies, the Cowpens prisoners who arrived via a different route and fleeing civilians across the Yadkin River at the Trading Ford, six miles east of Salisbury. For two days all the boats that could be mustered traveled back and forth across the muddy brown waters.

The British had reached Salisbury late in the day and pressed on to the Trading Ford, where they were in time to catch Greene’s rear guard still on the near side of the river. The Patriots passed down the river two miles and crossed over, abandoning the baggage and other wagons that could not be gotten over. The British marched on to the river, but found the water too deep to ford and still rising. It has always been believed that the Yadkin River rose suddenly after Greene crossed. All that is certain is that, by the time the British reached the Yadkin, it was too high to ford, and all the boats were on the far shore.

On February 4, the entire British army reached the south bank of the Yadkin. Cornwallis was eager to engage Greene’s army, but was separated from them by the width of the swollen river. He installed his artillery atop the nearest bluff, and furiously cannonaded the opposite shore. According to Dr. Joseph Read’s eyewitness account, General Greene had taken up quarters in a cabin not far from the river, and tended to correspondence while cannon balls flew about him.

Considering the conditions under which the Continental Army lived and fought, it is remarkable that they could even remain in the field, let alone fight a well equipped and supplied British army. The successful escape of Nathanael Greene’s army – whether by act of Providence, luck or military skill – preserved the American army’s strength against the British, who would lose many of their number at Guilford Court House come mid-March, and who would surrender at Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781.

Elizabeth Maxwell Steele was distinguished not only for her attachment to the American cause during the war, but for the piety that shone brightly in her useful life. She was a tender mother, and beloved for her constant exercise of the virtues of kindness and charity. Her daughter Margaret was the wife of the Reverend Samuel E. McCorkle, a famous scholar and divine. Her son John was to become the first comptroller of the United States appointed by President George Washington and retained by the next two presidents.

Elizabeth Maxwell Steele died in 1791, and was buried in Rowan County, North Carolina.

SOURCES

Elizabeth Steele

The Crossing of the Dan

Fateful Day at Trading Ford

Sons of the American Revolution

General Greene at Steele’s Tavern