Females Gathered Intelligence for the Patriot Cause

During the Revolutionary War, both the British and American armies recruited women as cooks and maids. With their almost unrestricted access, these women could eavesdrop on conversations in soldiers’ campsites and provide the critical intelligence they gathered to military and civilian leaders. Some reported directly to General George Washington, who came to highly value the information he received from these “agents in place.”

Spying on the Enemy

As their husbands, sons, brothers, fathers and uncles took up arms, these women served as the eyes and ears for military leaders, providing invaluable intelligence information throughout the war. Allied with either the British loyalist or American patriot cause, spy networks sprang up throughout the colonies.

More and more records are beginning to surface that suggest something of what these “patriots in petticoats” endured and contributed to the American Revolution. Aiding their cover were prevailing attitudes toward women by their male counterparts: females were considered innocent and non-threatening. As such, few commanders viewed these colonial homemakers as cause for concern, despite the fact that they were using women as secret agents to gather vital intelligence for their own armies.

Espionage and counterespionage were as commonplace during the 18th century as they were in the 20th century during the Cold War. During the Revolutionary War, spies for both England and America obtained and transmitted information about troop movement, supplies, fortifications, and political maneuvers. Loyalists in America (or Tories as they were often called) were happy to provide secret information to the Crown. Even Benjamin Franklin’s son William, who was a loyalist, spied on his own father and reported the elder Franklin’s activities to the British authorities.

In 1775, the Second Continental Congress created the Committee of Secret Correspondence, which was charged with gathering intelligence and “corresponding with our friends in Great Britain and other parts of the world” to gain information that would be helpful to the American cause and to forge alliances with foreign countries. Benjamin Franklin, who supervised the Committee’s work, worked closely with General George Washington, interpreting and directing foreign and military intelligence activities.

Even before setting up the Committee of Secret Correspondence, the Second Continental Congress had created a Secret Committee by a resolution on September 18, 1775. The Committee was given wide powers and large sums of money to obtain military supplies in secret, and was charged with distributing supplies and selling gunpowder to privateers chartered by the Continental Congress. The Committee also took over and administered the secret contracts for arms and gunpowder previously negotiated by certain members of the Congress without the formal sanction of that body.

The Secret Committee employed agents overseas, and gathered intelligence about Tory secret ammunition stores and arranged to seize them. They sent missions to plunder British supplies in the southern colonies, arranged the purchase of military stores through intermediaries so as to conceal the fact that the Continental Congress was the true purchaser, used foreign flags to protect its vessels from the British fleet.

On June 5, 1776, the Congress appointed John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Edward Rutledge, James Wilson, and Robert Livingston “to consider what is proper to be done with persons giving intelligence to the enemy or supplying them with provisions.” The same Committee was charged with revising the Articles of War in regard to espionage directed against the patriot forces. There was no civilian espionage act, and military law did not provide punishment severe enough to afford a deterrent, in the judgment of Washington and other Patriot leaders. On November 7, 1775, the Continental Congress added the death penalty for espionage to the Articles of War.

Methods of Espionage

Like modern secret agents, American and British spies during the American Revolution used a number of methods for hiding and transmitting information, including invisible ink, secret codes, and blind drops. A secret code would be set up that used letters or numbers to stand for other words. In order to decode the messages, the recipient needed a key or code book.

Several kinds of invisible ink were used by both sides during the war. One type was activated with heat and others by various chemicals. The invisible message was usually written between the lines of a letter, which would appear to be totally innocent. Upon receipt, the reader would either heat the letter over a flame or put it into a chemical bath to reveal the hidden message.

Letters or messages would be left at a blind drop, which was a location that was agreed upon in advance, such as a park bench or hollow tree. The message would be left by one person to be picked up later by another. Sometimes messages would be cut into slivers and stored in the hollow stem of a quill. Hollow silver balls were also used to store and carry messages. Not much larger than a musket ball, these balls could be easily concealed, or even swallowed if the messenger were captured.

With the British capture of Philadelphia on September 26, 1777, and with the Continental Army opposing the invaders with declining numbers, General Washington needed immediate, first-hand intelligence of the enemy’s intentions, motions, and condition. To supervise this vital work he sought for a man of intelligence and discretion, familiar with local inhabitants and locale, and who could be relied on to produce fresh, correct information by whatever direct or devious means were necessary. The General’s choice fell on Major John Clark Jr. of Pennsylvania, Aide-de-Camp to Major General Nathaniel Greene.

Although Clark’s assessments and information as chief of spies were not always exact (nor could they be expected to be in such a risky task), the correspondence between Washington and Clark reveals the exceeding pains and dangers experienced by Clark and his various spies to supply the Commander-in-Chief with the best advice possible.

George Washington was a skilled manager of intelligence. He utilized agents behind enemy lines, recruited both Tory and Patriot sources, interrogated travelers for intelligence information, and launched scores of agents on both intelligence and counterintelligence missions. Although he regularly urged all his officers to be more active in collecting intelligence, Washington relied chiefly on his aides and specially designated officers to assist him in conducting intelligence operations.

Probably the first Patriot organization created for counterintelligence purposes was the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. It was made up of a series of groups established in New York between June 1776 and January 1778 to collect intelligence, apprehend British spies and couriers, and examine suspected British sympathizers. In effect, there was created a “secret service” for New York which had the power to arrest, to convict, to grant bail or parole, and to jail or to deport.

Nathan Hale

The young man named Nathan Hale is probably the best known but least successful American agent in the War of Independence. After a crushing defeat at the Battle of Long Island, Washington called for a volunteer to spy on the British and report to the American command with details of future battle plans. Hale volunteered, but he had no training, no contacts in New York, and no channels of communication. He was captured behind enemy lines while trying to slip out of New York, was convicted as a spy and went to the gallows on September 22, 1776, where he said, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

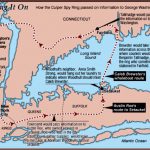

The Setauket Spy Ring

While the British controlled New York City, there was much that the commander in chief needed to know: the sizes and numbers of vessels in the harbor and how they were protected; the number of men guarding the city, and how they were deployed; descriptions of forts and redoubts that had been built by the British; the state of the provisions, forage, and fuel to be attended to, as also the health and spirits of the army, navy, and City.”

The Setauket spy ring began its activities on a small scale in 1778, with Abraham Woodhull, alias Samuel Culper, doing much of the snooping in New York. The ring employed both men and women, and based its operations in New York and Long Island. Most members of the espionage group used their professions as cover, relying on customers and patrons from the British military to divulge information about British military operations voluntarily. Several members of the Culper Ring were caught by British occupation authorities, but the ring never stopped feeding information to American authorities during the war.

Agent 355

355 was the numeric substitution code designation used by the Setauket Spy Ring to represent the word woman. This agent was referred to simply as 355 to protect her work and life. She supplied timely and accurate information to General Washington, played an important role in counterintelligence missions that uncovered Benedict Arnold’s treason, and facilitated the arrest of Major John André, head of England’s Intelligence Operations in New York. Her true identity remains a mystery today.

Anna Smith Strong

The spies in the Setauket Spy Ring included a Long Island woman who was a strong and ardent patriot. Anna Smith Strong devised a wash line signal system to identify for Abraham Woodhull the whereabouts of Caleb Brewster’s Whaleboat, so that Woodhull could find him and pass along the messages meant for General Washington. To avoid detection by the British, Brewster had to hide his boat in six different places, each identified by a number.

Image: Clothesline Signal System

Anna Strong hung laundry on the clothesline in a code formation to direct Woodhull to the correct location. A black petticoat was the signal that Brewster was nearby, and the number of handkerchiefs scattered among the other garments on the line showed the meeting place. Using the most ordinary of personal items and improvising on the most ordinary of personal tasks, Strong made an extraordinary contribution to the cause of freedom.

Lydia Darragh

Officers of the British forces occupying Philadelphia used a large upstairs room in the Darragh house for conferences. When they did, Lydia Darragh would slip into an adjoining closet and take notes on the enemy’s military plans. Her husband, William, would transcribe the intelligence in a form of shorthand on tiny slips of paper that Lydia would then position on a button mold before covering it with fabric. The message-bearing buttons were then sewn onto the coat of her fourteen-year-old son, John, who would then be sent to visit his elder brother, Lieutenant Charles Darragh, of the American forces outside the city. Charles would snip off the buttons and transcribe the shorthand notes into readable form for presentation to his officers.

Ann Bates

Ann Bates was a loyalist spy for the British forces. She was a teacher in Philadelphia, and began spying for the British sometime in 1778. She posed as a peddler, selling thread, needles, knives, and utensils to the American camp followers. In this manner, Bates traveled through rebel camps, counting the number of men and weapons, and meeting with other loyalist sympathizers in the American army. On May 12, 1780, Bates requested to leave Clinton’s espionage ring and join her husband, a gun repairman with the British Army, in Charleston, South Carolina.

Many other heroic Patriots gathered the intelligence that helped win the War of Independence, and their intelligence duties required many of them to pose as one of the enemy, incurring the hatred of family members and friends – some even having their property seized or burned, and their families driven from their homes. Many of them gave their lives to help establish America’s freedom.

After the end of the Revolution, and the establishment of an independent United States government, most military and espionage institutions were dissolved. Until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, American intelligence agencies and services were exclusively wartime organizations, rapidly assembled in times of conflict, and dissolved in times of peace.

SOURCES

Female Agents

Spy System 1777

World of Influence

The American Revolution

Spy Letters and the Revolution

Intelligence in the Revolutionary War

Intelligence in the War of Independence