Civil War Nurse in Mississippi

Of all the families in Raymond, Mississippi, during the Civil War, one of the most affected was that of Augustine and Elizabeth Dabney. Augustine was a probate judge and worked hard to support his family of ten children. His wife and daughters helped to nurse the wounded soldiers following the Battle of Raymond on May 12, 1863.

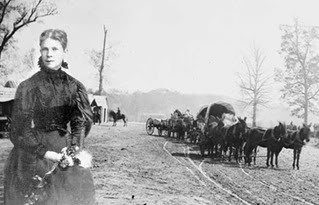

Image: Mary Dabney and Big Black River Station

Photo superimposed by James Drake

In August 1863, Mary Dabney went to Vicksburg to apply for a share of the livestock and supplies that had been confiscated by the Union army on their march to Vicksburg, which was being given away by General Ulysses S. Grant.

In August 1863, Mary Dabney went to Vicksburg to apply for a share of the livestock and supplies that had been confiscated by the Union army on their march to Vicksburg, which was being given away by General Ulysses S. Grant.

The following is Mary’s account of that journey, during which she met and visited with the three most prominent officers of the Union Army: Grant, Sherman and McPherson.

Seeking Supplies in Vicksburg

We heard that General Grant was giving away the wagons and mules driven into Vicksburg from the plantations on the route of his march. It was decided that Kate Nelson [friend] and I should go to Vicksburg and obtain transportation from General Grant in person with a safe conduct from him through the Union lines.

One evening late, just as this decision had been reached, a lady of our acquaintance, Mrs. McCowan, came over to see me. She had heard that I wanted to go to Vicksburg. She could furnish a vehicle and a horse and would willingly take me if my youngest brother, John Davis, could drive us. She protested, however, that it would not be possible to take Kate, as there was positively no room for another person.

On August 15, Mary and Mrs. McCowan took their seats in a wagon driven by Mary’s brother, and left for Vicksburg at the crack of dawn.

Arriving at Big Black River Station

We got off very early next morning. My brother, though quite young, was an experienced driver, for it was he who made the weekly trips to Burleigh, my uncle’s plantation, for meal, corn and an occasional piece of fine beef or mutton when the family were there, but they were at that time refugees in Georgia, and that resource for us had been cut off.

We reached Big Black station about the middle of the day. There was an important Union garrison at this point. We asked to see the commanding general [Grant] who assured me most courteously that our horse, which needed rest very much, should be cared for, and that meantime we were welcome to the hospitality of his tent.

Soon after our arrival there, he invited us to dine with him. To have accepted dinner from a Union General would have been of course rank disloyalty, perhaps even treason, to the Confederate cause. We replied with thanks that we had brought our lunch with us.

We partook therefore of this meager and unappetizing cold meal, while odors of the most alluring nature from that hot dinner came floating in to us. We were sustained, however, by the thought of our patriotic devotion to the Confederacy.

General William Tecumseh Sherman had come over from Vicksburg to meet his wife and daughter who were arriving from Ohio. The two Generals sat and conversed while waiting for the Sherman ladies. He [Sherman] said he was persuading General Grant that the only way to end the war was devastate the country, for the men would not remain in the Southern army if they knew their wives and children were homeless and hungry.

He was so intent on demonstrating to his tenderhearted host the correctness of his theory that he took no thought of the two silent women on whom his words fell like the doom of an impending fate. Sherman mentioned in particular that he wanted to make the civilians in Mississippi suffer as a means of winning the war. He even felt that the Union army had the right to take the life and property of any civilian who did not aid their cause. Mary and Mrs. McCowan were silently weeping when they left the tent to return to their wagon.

Meeting General Grant

When we reached Vicksburg, Mrs. McCowan and I parted, each going to our respective friends. My brother John Davis and I were received most hospitably by Mrs. Creasy and her mother, Mrs. Pryor, whom we had often seen at our house in Raymond.

Mrs. Creasy promised to take me next day to General Grant’s headquarters. She said she knew one of his staff very well, Colonel [Harrison] Strong. This officer received us cordially as an old friend of Mrs. Creasy. We were taken immediately to General Grant.

The General ordered him [his chief of staff] to make out a paper entitling me to receive two wagons and four mules. When this precious document was safe in my hands, my peace of mind was restored. In spite of deep seated prejudice, I had to acknowledge to myself that General Grant was a very humane man, and I felt sure he could never commit a cruel act, that he would inevitably err if err it were, on the side of clemency.

In comparing the two men, General Grant and General Sherman, I felt and still feel sure that General Grant accomplished more by his kind heart than Sherman by his theory of ruthlessness. The latter took no thought of the soul of man which is not like that of any other of God’s creatures. Men bend to force, but hatred smolders in their hearts. All this, however, is only stating in other words the old truth that Christianity is true statesmanship in dealing with a conquered foe, that evil cannot be overcome with evil.

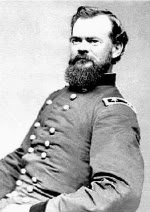

Visiting General McPherson’s Headquarters

That evening Mrs. Creasy took me to General [James B.] McPherson‘s headquarters to get from him the order for two more wagons and four more mules for the Nelson family [of Raymond]. Mrs. Creasy agreed with me that this was better than to ask General Grant for all the transportation.

It occurred to me, however, afterwards, that one of these two Generals might well have mentioned my mission to the other, and then what would they have thought of a young woman who sought by deception to acquire more than a just proportion of the plunder of Southern plantations!

This thought tortured me and I felt sure I could have confided to General Grant the whole story, and Mrs. Creasy was there to corroborate it, but it is my fate always to commit mistakes and repent of them when too late.

General McPherson now took out some letters he had received from Southern ladies proving how lenient he had been in carrying out his instructions, how he had sympathized with them in their unmerited sufferings, privations, etc. He wanted me to read them.

Now if there was one thing I dreaded more than another it was to be asked to read strange handwriting in public. I was therefore unwilling to make a spectacle of myself before General McPherson and Mrs. Creasy and got out of it as best I could by asking him questions. Why he cared in the least for my conversation is more than I can tell. I suppose that being in an enemy country he was deprived of ladies’ society.

I am very sure that if he had cultivated women to talk to he would never have listened to me, who had been born and bred in a town smaller than any Northern village; but whenever Mrs. Creasy would propose to go he would beg her to stay just a little longer, till that good lady, who took not the slightest interest in our conversation, got out of all patience and dragged me off.

Next morning, General McPherson said, “I have ridden all over Vicksburg this morning but I can find no harness anywhere.” I had never thought of harness, but now piqued and mortified, I said: “So your gift was not a real one. You knew I should not be able to get the wagons and mules to Raymond.”

Without appearing to notice this ungrateful and impertinent remark, the General said gravely, “I think I can give you some good advice. In the Confederate hospital there are some wounded men most anxious to leave. Give my order to them, and if there is a harness still in Vicksburg they will find it.”

He mounted his horse and rode away. I believe he was killed soon afterwards in Tennessee, one of the noblest and most chivalrous men produced on either side of that war.

Leaving Vicksburg

My one desire at that moment was to leave Vicksburg and get home as soon as possible. Without asking Mrs. Creasy to accompany me, I started off immediately to the Confederate Hospital. There I was brought before the superintendent, a Northern man. I told him my business in a few words.

He looked at me with what appeared to be withering contempt and said: “At your age, young ladies in the North stay home with their parents and leave business to men.” I really did not need any more mortification that morning, and this blow overwhelmed me. I handed him two orders, and said I was told to come there. I did not attempt to justify myself.

When I reached home, I found my uncle [Thomas Dabney] there, who had persuaded my father to rent out his Raymond house and move to Burleigh, my uncle’s plantation. The family were refugees, and the slaves too had been taken away, so someone was needed to protect the property. My father was greatly elated by my success in Vicksburg for the wagons and mules would enable him to cultivate the kitchen garden and a field at Burleigh with the slaves who had not left us.

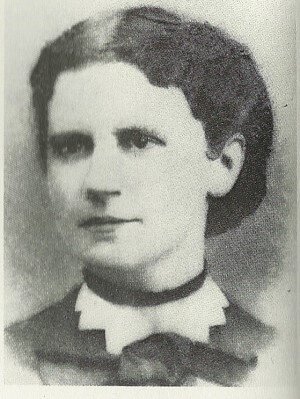

Lt. William Lynch Ware, a Confederate officer who had been wounded in both legs during the Siege of Vicksburg was brought by ambulance to Raymond where he convalesced briefly in the Dabney home. Mary Dabney and William were married a short time later.

Following the war, Mary and William moved to Jackson, Mississippi. After the death of her husband, Mary traveled extensively and often visited Sewanee, Tennessee, where many of her sisters and cousins lived. Mary eventually moved to Europe, where she traveled and lived for fourteen years.

At the time of her death, Mary Dabney Ware was living in Jackson, Mississippi, and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery there.

SOURCES

History of Raymond

Behind Enemy Lines

History of Raymond Mississippi

Mary Dabney Meets Generals Grant, Sherman, and McPherson