Women’s Rights in Cherokee Society

Image: Loving Sun

Marianne Caroselli, Artist

(I know the Cherokee did not live in teepees; I just love this painting.)

In the early 18th century, the Cherokee existence was one marked by balance guided by oral tradition. Their belief in balance in all aspects of life didn’t leave room for a system of hierarchy that oppressed women. Men primarily assumed the roles of hunters, while women took responsibility for agriculture and gathering.

At the time of European contact, the Cherokee controlled a large area of what is now the southeastern United States. Of the southeastern Indian confederacies of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw), the Cherokee were one of the most populous and powerful, and were relatively isolated by their hilly and mountainous homeland.

Until the latter part of the eighteenth century, Cherokee lands included portions of the current states of Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. Although there was some trading contact, the Cherokee remained relatively unaffected by the presence of European colonies until the Tuscarora War (1711-1715) and its aftermath.

The women in Cherokee society had the same rights as men. Long before the arrival of the white man, women enjoyed a major role in the family life, economy, and government of the Cherokee. They lived in villages built along the rivers of western North Carolina, northwestern South Carolina, northern Georgia, and eastern Tennessee. When white men visited these villages in the early 1700s, they were surprised by the rights and privileges of Indian women.

Perhaps most surprising to Europeans was the matrilineal kinship system, in which a person is related only to people on his mother’s side. His relatives are those who can be traced through a woman, meaning that a child is related to his mother, and through her to his brothers and sisters, his mother’s mother (grandmother), his mother’s brothers (uncles), and his mother’s sisters (aunts).

A child wasn’t related to the father. The most important male relative in a child’s life is his mother’s brother. Many Europeans never figured out how this kinship system worked. Those white men who married Indian women were shocked to discover that the Cherokee did not consider them to be related to their own children, and that mothers had control over the children.

Europeans were also astonished that women were the heads of Cherokee households. They lived in extended families, meaning that several generations (grandmother, mother, grandchildren) lived together as one family. Such a large family needed a number of different buildings. The roomy summer house was built of bark. The tiny winter house had thick clay walls and a roof, which kept in the heat from a fire smoldering on a central hearth. The household also had corn cribs and storage sheds.

All these buildings belonged to the women in the family, and daughters inherited them from their mothers. A husband lived in the household of his wife (and her mother and sisters). If a husband and wife did not get along and decided to separate, the husband went home to his mother while any children remained with the wife in her home.

In stark contrast to their late eighteenth-century white contemporaries, Cherokee women could own property, vote in elections, and file for divorce. Women’s labor formed the backbone of Cherokee culture. They cultivated the corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, and pumpkins that fed all Cherokee. Each family was allotted space for a garden inside the village, and for larger crops, a section of the large fields outside the village.

Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, Cherokee women did most of the farming. They were horticulturalists, raising cereal and vegetable crops that fed all Cherokee – beans, squash, pumpkins, sunflowers, sweet potatoes, peaches and watermelons. The burden of a successful harvest rested on Cherokee women. Since corn was the principle staple that Cherokee life depended on, it gave to women considerable economic power and status.

Each year in late September, the Cherokee tribe gathered to honor Selu, the Corn Mother, who, according to tribal traditions, gave up her life so that her sons, and subsequently all Cherokee people, would have enough to eat. This worship of Selu, who passed her essential ability to provide food and sustain life to all Cherokee women, helps explain the power females held within the matrilineal tribe.

In the winter when men traveled hundreds of miles to hunt bears, deer, turkeys, and other game, women stayed at home. They kept the fires burning in the winter houses, made baskets, pottery, clothing, and other things the family needed, cared for the children, and performed the chores for the household.

Perhaps because women were so important in the family and in the economy, they also had a voice in government. The Cherokee made decisions only after they discussed an issue for a long time and agreed on what they should do. The council meetings at which decisions were made were open to everyone including women.

Women participated actively at council. Sometimes they urged the men to go to war to avenge an earlier enemy attack. At other times they advised peace. Women occasionally even fought in battles beside the men, and were called War Women, and the people respected and honored them for their bravery.

During the early 18th Century, the increased slaughter of deer for the fur trade altered the work routines of Cherokee women. Cherokee women prepared the deerskin for trade through the long and tedious process of “scraping, drying, soaking, and smoking to remove tissue and hair,” prevent decay, and worm and maggot infestation. This work took away time for other work. Men, then, traded the deerskins to Europeans in exchange for consumer goods that rapidly became necessities.

The adoption of more intensive agricultural methods during the eighteenth century further altered the traditional division of labor, and men replaced women in the fields and Cherokee women’s work was increasingly confined to the household.

According to Thomas Jefferson, the federal policy of Indian acculturation would teach the Cherokee to adopt the economic philosophy of private ownership, and European laws and government. The purpose of the civilization program was to assimilate the Cherokee into white society.

With the help of missionaries, whose goal was to civilize and Christianize the Cherokee, government agents began exposing the Indians to European agricultural practices. Cherokee men were given plows, livestock, and gristmills; the women were provided with cloth and spinning tools. Around 1739, Cherokee women began growing cotton and flax, and they became expert spinners and weavers.

Women’s clothing also changed. In the early 18th century, Cherokee women wore mantles of leather or feathers, skirts of leather or woven mulberry bark, front-seam moccasins, and earrings pierced through the earlobe. By the end of the 18th century, Cherokee women were dressing like their white neighbors – in calico skirts, blouses, and shawls.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Cherokee population had been reduced by disease and warfare, and treaties with the English significantly decreased their landholdings. Cherokees fought in numerous military conflicts during the eighteenth century, including the Cherokee War against the British and the American Revolution, in which they fought against the colonies.

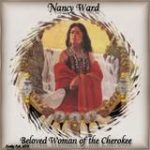

Image: Sequoyah and his Alphabet

During the early 1800s, the Cherokee adopted their own government, wrote a constitution, and established their own courts and schools. Particularly noteworthy was the invention of a written language by the Cherokee scholar Sequoyah in 1821. Utilizing an ingenious alphabet of 86 characters, almost the entire Cherokee Nation became literate within a few years. A Cherokee newspaper, the Phoenix, began publication in the native language in 1828.

But because of the influence of European immigrant culture, many Cherokee began abandoning their traditional towns and lived in family groups in log cabins along the streams and river valleys. Although the land was still owned communally, the Cherokee took on a type of subsistence farming on small plots normally ranging from two to ten acres in size.

The Cherokee lost their independence and were dominated by white Americans, who believed that it was improper for women to fight in wars, vote, speak in public, work outside the home, or even control their own children. The Cherokee began to imitate whites, and Cherokee women lost much of their power and prestige.

Circumstances continued to deteriorate, and in the mid-1800s the Cherokee were forced to abandon their eastern homelands and walk hundreds of miles to reservations in eastern Oklahoma in a journey that became known as the Trail of Tears.

I will save that story for another post; it makes my Cherokee blood boil.

SOURCES

Cherokee Women

Cherokee Economy

Wikipedia: Cherokee

Cherokee Marriage Customs

Cherokee History and Culture

Cherokee Food and Subsistence Practices

I live in Blk Mtn. N. C. . I am interested in learning more about the Cherokee people. I have been told that my great grandmother was full Cherokee. I would be very proud of she was.

There were people who carried the surname Williams who fought as allies of the Chickamaugans from 1775 to 1794. The Chickamaugans (Cherokees, Shawnees, Creeks, former slaves, British loyalists, and other Native Americans who joined them) declared war on the United States in 1792 and fought against the rebels/patriots for nineteen years in order to retain their hunting grounds that had been illegally sold to the Transylvania Company (a land speculation company). I have a book coming out in December 2022, Multitribal Indians in Search of No Man’s Land: The American Expansion and the Chickamaugans Between Resistance and Migration. Carla Toney ([email protected])

I was told my grandmother “Lucy” was full blooded Cherokee. Birthed my great gra nd father by a white man name Bobo.

My great granfathef name was Randel Bobo from “Bobo, MS.”