History of Slavery in South Carolina

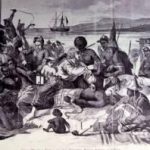

Image: Plantation Dance in South Carolina

This well-known watercolor by an unidentified artist depicts people presumed to be plantation slaves dancing and playing musical instruments. It gives a rare view of African American life in South Carolina during the colonial period. The women are wearing head wraps and gowns with fitted bodices and long full skirts. Some of the men are wearing earrings. Although its setting is uncertain, materials in the files of Colonial Williamsburg suggest a plantation between Charleston and Orangeburg, South Carolina.

Conditions in the South were favorable for slavery. Large stretches of fertile land, a warm climate that the Negroes tolerated much better than the whites, and unhealthy regions where white men did not care to work – all these drew slavery to America. Established first in the Spanish possessions of the West Indies, it spread as soon as the mainland was settled along the mainland, from Jamestown northward and southward.

Land for Slaves

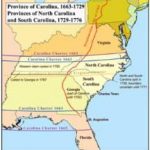

Slavery was encouraged from the outset of the Carolina Colony. The four proprietors of the colony were members of the Royal African Company, a slave trading company. In 1663, the proprietors encouraged settlers to acquire slaves with the promise that they would be given 20 acres of land for every black male slave and 10 acres for every black female slave brought to the colony within the first year. This encouragement worked; by 1683, the black population was equal to the white population.

Colonial Slavery

South Carolina was a slave colony from its inception. Although the first Africans arrived in 1526 as part of a large Spanish expedition from the West Indies, planters who later emigrated from Barbados established large scale slavery in the Carolinas on indigo and rice plantations.

Africans were experienced in working with these crops and adapted well to South Carolina’s hot and humid climate. The black population outnumbered whites by 1708, and remained in the majority in the Low Country along the coast, even as whites began filling up the back country starting in the 1740s.

Black slavery was legally recognized by the Carolina Grand Council in 1669, and a number of specific statutes were passed beginning in 1686 to control the emerging slave population. The code established a slave’s status as freehold property, which was a higher level of property than chattel.

Freehold property in theory could not be moved or sold from the estate, similar to the position of medieval serfs who were tied to specific farms or feudal estates. The slaveholder had use of an enslaved person’s services, but could not claim absolute ownership.

By 1696, however, the status of enslaved Africans in South Carolina had been degraded to chattel property in law and in practice. Enslaved blacks, mulattoes, and American Indians could be bought and sold, and their children were enslaved for life.

In addition to defining the status of enslaved blacks, the code explicitly spelled out the punishment for those who struck a white person and for runaways. First offenders were severely whipped, followed by slitting the nose and burning “some part of his face with a hot iron,” and even death for those who attacked whites a second or third time.

Enslaved blacks found off the plantation without written permission from their master were considered runaways. Those who ran away more than once could be branded with an R on their cheek and might suffer the loss of an ear. Castrating male slaves and branding an R on the left cheek of female slaves punished a fourth offense. A fifth failed attempt could be punished by either cutting the tendon in one leg or sentencing the enslaved person to death.

Manumission

The freeing of enslaved persons – manumission – was not regulated by statute in South Carolina until 1712, when the colonial legislature decreed that slaveholders or the colonial governor or provincial council could manumit enslaved persons for good cause. Later legislation stated that manumitted blacks had to leave the colony. If the freed person failed to leave South Carolina within six months, he or she would be re-enslaved and sold at public auction.

By 1800, manumission laws had become more stringent. In response to some slaveholders who freed troublesome or debilitated blacks who then became burdens on the community, the legislature required the approval of a commission for any future manumissions. By 1820, enslaved African Americans could only be freed by an act of the legislature. Other statutes, such as one passed in1822, prohibited free blacks from entering the state.

Slave Codes

As the black population continued to increase, South Carolina lawmakers feared the consequences of a black majority and tried to halt the importation of slaves. A 1716 statute required planters to import one white servant for each ten slaves. A bounty of 25 pounds was also paid for each white servant imported.

In 1719, a duty of 10 pounds for African blacks was assessed on importing slaveholders and 30 pounds for blacks from the West Indies. (South Carolina whites believed that blacks from the West Indies were more rebellious than slaves imported directly from Africa.)

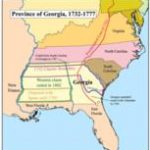

South Carolina passed a new slave code in 1740, more commonly known as the Negro Act. The code, which was passed in response to the Stono Rebellion of 1739, remained largely unaltered until emancipation in 1865. The act also served as a model for the Georgia slave code of 1755. The new code further stripped enslaved blacks of any kind of protection under the law.

Punishment for the murder of an enslaved person by a white, for example, was reduced to a mere misdemeanor punishable by a fine. Slaves could never physically attack a white person except in defense of the slaveholder who owned them. They could be executed for plotting insurrection or conspiring to run away, for burning a barrel of tar or a “stack of rice,” or for teaching another slave “the knowledge of any poisonous root, plant, [or] herb.”

Much of the Negro Act was devoted to controlling minute aspects of a slave’s life. For example, slaves were not allowed to dress in a way “above the condition of slaves.” Their clothes could only be made from a list of approved coarse fabrics. Blacks were prohibited from learning how to read and write, and were not permitted to assemble with one another. Blacks in violation of these provisions were subject to flogging.

Criminal trials for enslaved blacks were often held in a local tavern or country store. The mixing of alcohol with the drama of a black defendant on trial often for his or her life created a bawdy and raucous atmosphere. One historian found that between the passage of the Negro Act of 1740 and the beginning of the American Revolution, at least 191 enslaved blacks received the death penalty for a criminal offense.

Between 1750 and 1759, nearly 63 percent of the slaves executed were convicted of a violent crime against a white. Another 16 percent were convicted of a violent offense against a slave. Two blacks were convicted of a property crime (arson, burglary or theft), and only one enslaved black was found guilty of conspiring to revolt.

Antebellum Slavery

In 1792, South Carolina passed “an Act to prohibit the Importation of Slaves from Africa, or other places beyond the sea, into this state, for two years.” By 1800, slaves could not be imported from offshore, and no one could bring in more than ten slaves from anywhere in the country.

Between 1800 and 1854, nearly 58 percent of the South Carolina enslaved blacks executed were convicted of a violent crime and 21 percent for a property offense. Another 21 percent were executed for insurrection, a result of the Denmark Vesey conspiracy of 1822.

These efforts did little to curb black population growth in South Carolina. By 1860, more than 400,000 enslaved blacks lived in South Carolina, representing 58 percent of the population. And the large majority of these enslaved people had been born in the state as second and third generation African Americans.

SOURCE

Slavery in the Colonial United States