Civil War Nurse in Washington, DC

In 1803, some families from Bristol and Meriden, Connecticut, moved to the wilderness of New York, and settled in what is now Otisco, Onondaga County. Among these were Chauncey Gaylord, a sturdy, athletic young man, just arrived at the age of twenty-one, and “a little, quiet, black-eyed girl, with a sunny, thoughtful face, only eleven years old.” Her name was Dema Cowles.

In 1803, some families from Bristol and Meriden, Connecticut, moved to the wilderness of New York, and settled in what is now Otisco, Onondaga County. Among these were Chauncey Gaylord, a sturdy, athletic young man, just arrived at the age of twenty-one, and “a little, quiet, black-eyed girl, with a sunny, thoughtful face, only eleven years old.” Her name was Dema Cowles.

So the young man and the little girl became acquaintances, and friends, and in after years lovers. In 1817 they were married. Their first home was of logs, containing one room, with a rude loft above, and an excavation beneath for a cellar.

In this humble abode was born Lucy Ann Gaylord, who afterwards became the wife of Samuel C. Pomeroy, United States Senator from Kansas. Mrs. Gaylord was a woman of remarkable strength of character and principles, one who carried her religion into her daily life, and taught by a consistent example.

Lucy’s mother had early been widowed, and had afterwards married Eliakim Clark from Massachusetts, and had become the mother of the well-known twin brothers, Lewis Gaylord, and Willis Gaylord Clark, destined to develop into scholars and poets, and to leave their mark upon the literature of America.

Lucy, and as the elder sister, shared in their primitive mode of life, and in her mother’s cares and duties. Her character developed and expanded, and she grew in mental grace as in stature, loving all beautiful things and noble thoughts, and early making a profession of religion.

By this time, the family occupied a handsome rural homestead, where neatness, order, industry, and kindness reigned, and where a liberal hospitality was always practiced. Here gathered all the large group of family relatives, and here the aged grandmother Clark lived.

The most beautiful scenery surrounded this homestead. Peace, order, intelligence, truth, and godliness abounded there, and amidst such influences Lucy Gaylord had the training that led to the future usefulness of her life. Even in her youth, she was the friend and safe counsellor of her brothers.

At eighteen, Lucy dedicated herself to missionary work. To this end she labored and studied for several years, steadfastly educating herself for a vocation she believed was her calling, though often afflicted with serious doubts as to whether she could leave her parents.

One violent illness after another destroyed Lucy’s health, and she never quite recovered the early tone of her system. Yet she worked on, doing good wherever possible. Soon afterwards she met with the great sorrow of her life. The young man to whom she was soon to be married, to whom she had a very strong attachment, died suddenly. By degrees the sharpness of her grief wore away, and it became a sweet, though sad memory.

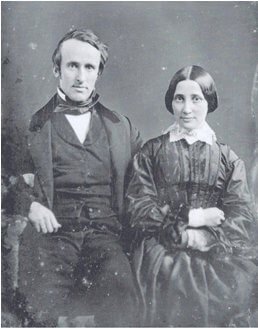

Eight years later, Lucy married Samuel C. Pomeroy of Southampton, Massachusetts. He had given up mercantile business in Western New York not long before, and had returned to his childhood home to care for his aged parents. Lucy was welcomed heartily, and she took on the duties of caring for Samuel’s parents.

Here, as elsewhere, Lucy made herself useful beyond, as well as within, her home. She performed duties of Sabbath School teacher and general religious instruction, that might be called arduous, especially when added to her domestic cares and occupations.

All these labors eventually exhausted Lucy’s strength, and a protracted illness followed. From 1850, for five or six years, she continued to suffer, being most of the time very ill. During all this time, however, she never lost her faith and courage, even when her physicians gave no hope of her recovery, being convinced that if God had any work for her to do, He would spare her life.

During this time her husband was often absent, being first in the Massachusetts Legislature, and later an agent of the Northeastern Aid Society of Kansas, which they wanted to settle as a free State. During his absence, she experienced other afflictions, but her health finally improved, and as soon as possible she made preparations to go to Kansas, where Mr. Pomeroy wanted to make a home.

In the spring of 1857, Lucy finally arrived there. The hardships and the usefulness of her life in Kansas are matters of history, and it is surprising that one so long an invalid was enabled to perform such exhausting labors. All who knew her there, bore enthusiastic testimony to the usefulness of her life.

To the whites, Lucy was friend, hostess, counsellor, assistant, in sickness and in health. To the poor and despised blacks, striving to find freedom, she was friend and teacher, even at a time when – with the slave state of Missouri so nearby – that service was most dangerous.

Then followed the terrible famine year of 1860. During all that time, Lucy freely gave her services in the work of providing for the sufferers. Mr. Pomeroy, aided by the knowledge he had acquired in his experience as Agent of Emigration, was able to obtain supplies from the East, and Mrs. Pomeroy transformed her home into an office of distribution, of which she was superintendent and chief clerk. It was a year that taxed her strength far too heavily.

Lucy accompanied her husband to Washington in the spring of 1861 to take his seat in the United States Senate. There, her health failed again. Cough and hoarseness constantly troubled her, and at times she was obliged to leave for visits in her native air, and for a stay of some months at the Geneva Water Cure.

From the very beginning of the Civil War, Lucy Pomeroy proved herself desirous of the welfare of our soldiers. The record of her deeds of kindness is not as ample as that of some others, because her poor health forbade active nursing and visiting the hospitals, which is the most public part of the work.

Lucy went home to Kansas in the autumn of 1862, and spent some months there. There was at that time a regiment in camp at Atchison, and she was able to do great good to the sick in the hospital – not only with supplies, but by her own personal efforts for their physical and spiritual welfare.

On her return to Washington, Lucy entered as actively as possible into caring for the soldiers. Her form became known in the hospitals, and many a suffering man hailed her coming with a new light kindling in his dimmed eyes. She brought them comforts and delicacies, and added her prayers. She cared both for souls and bodies, and earned the immortal gratitude of those to whom she ministered.

In January 1863, Lucy’s last active benevolent work began – the foundation of an asylum at Washington for the freed orphans and destitute aged African American women whom the war, and the Proclamation of Emancipation, had thrown upon the care of the benevolent. A charter was immediately obtained, and when the Association was organized, Mrs. Pomeroy was chosen President.

Almost entirely by her exertions, a building for the Asylum was obtained, as well as some condemned hospital furniture, which was to be sold at auction by the Government, but was instead transferred to the Asylum. But when the time came, on June 1, 1863, for the Association to be put in possession of the buildings and grounds assigned them, Mrs. Pomeroy was too ill to receive the keys, and the Secretary took her place. She was never able to look upon the fruit of her labors.

Again, Lucy had exhausted her feeble powers, and she was never more to rally. A slow fever followed, which at last assumed the form of typhoid. She lingered on, slightly better at times, until July 17, when preparations were completed for removing her to the Geneva Water Cure, and she started upon her last journey.

She went by water, and arrived at New York very comfortably, leaving there on a boat for Albany, on the morning of the July 20. But death overtook her before even this portion of the journey was finished.

Lucy Gaylord Pomeroy died on the afternoon of July 20, 1863.

SOURCE

Woman’s Work in the Civil War