Civil War Nurse

Fanny Lawrence was the daughter of an Englishman of wealth, J. Sharpe Lawrence, who owned large estates on the Island of Jamaica. Her parents were married at Elizabeth, New Jersey, and after some years of migratory life between England and the West Indies, decided to remain. There their third daughter Fanny was born.

Fanny Lawrence was the daughter of an Englishman of wealth, J. Sharpe Lawrence, who owned large estates on the Island of Jamaica. Her parents were married at Elizabeth, New Jersey, and after some years of migratory life between England and the West Indies, decided to remain. There their third daughter Fanny was born.

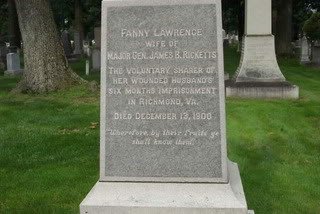

Image: Fanny and James Ricketts

In January, 1856, Fanny Lawrence married James B. Ricketts, a distant relative on her mother’s side who was then a captain in the First Artillery, U. S. Army. James was a career soldier who held the rank of captain. He was a graduate of West Point, and fought in both the Mexican and Seminole Wars and served in various garrisons.

Immediately after the wedding, Fanny went with him to the Southwestern frontier on the Rio Grande River, where his company was stationed. When in camp, Fanny greatly endeared herself to the men in her husband’s company by constant acts of kindness to the sick, and by showing a cheerful and lively disposition amid all the hardships and annoyances of garrison life at such a distance from home.

James Ricketts in the Civil War

At the beginning of the Civil War, the First Artillery was ordered to report to Fortress Monroe in Virginia, where Fanny’s husband trained the new recruits in artillery. James served in the defenses of Washington, DC, and commanded an artillery battery in the capture of Confederate-held Alexandria, Virginia, in early 1861. His battery was then attached to William B. Franklin’s Brigade of Samuel Heintzelman’s Division.

First Battle of Bull Run

James Ricketts was shot four times and captured at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, when his battery was overrun by Confederate infantry. For his personal bravery in the face of overwhelming odds, Ricketts was promoted to the rank of brigadier general of U.S. volunteers.

Fanny Ricketts was in the vicinity of the capital during First Bull Run. When her husband did not return with the rest of his unit, she was able to obtain a pass to go through the Union lines directly to the battlefield. She set out alone from their home in Washington, DC, determined to find her husband.

When she encountered a Confederate outpost, her pass was worthless, and she feared she may have to turn back. Fanny remembered her husband had a friendship with J.E.B. Stuart before the war, and she was able to contact him at Fairfax Court House. Now a professional soldier wearing the uniform of a Confederate colonel, Stuart gave Fanny a pass allowing her passage to the battlefield.

After four days of searching, Fanny finally found her husband in a makeshift hospital. From there she accompanied him as a prisoner of war to Richmond, and went into captivity with him. There she stayed, made friends with the prison guards to gain visiting privileges, and saw her husband almost daily.

Excerpts from Fanny Ricketts’ diary:

July 26:

No words can describe the horrors around me. Two men dead and covered with blood were carried down the stairs as I waited to let them pass. On a table in the open hall, a man was undergoing amputation of the leg. At the foot of the stairs two bloody legs lay, and through it all I went to my husband. Outside the next door was a severed arm, and my clothes brushed by blood, cloths, splint, etc. I found my dear husband lying on a hospital stretcher, still covered with blood! Downstairs, there are some forty men in the various stages of death or possible recovery. Blood runs on the floors, the smell is dreadful but no language can describe it.July 27:

Dear James passed a restless night, his knee is much inflamed. Oh God, grant my darling husband be spared his leg. I was awake all night, the groans of the dying sounding in my ears. As I look from the window I see a severed leg under a tree. It has been there all day, and I intend asking to have it removed.

It required all of Fanny’s courage to endure the hardships, privations and cruelties to which the Union women were subjected, and while caring for her husband during the long weeks when his life hung upon a slender thread, she became also a nurse to the numerous Union prisoners, who had no one to care for them.

When removed to Richmond, Captain Ricketts was still in great peril, and grew rapidly worse. For many weeks he was unconscious, and his death seemed inevitable. At length, four months after receiving his wounds, he began very slowly to improve. James was exchanged in the latter part of December, 1861, having partially recovered.

In March 1862, Ricketts was assigned to command a brigade in General Irvin McDowell‘s Corps at Fredericksburg. He commanded at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, where he covered Nathaniel P. Banks’ withdrawal.

At the Second Bull Run, Ricketts’ division was thrown forward into Thoroughfare Gap to bar the advance of Confederate General James Longstreet, who was trying to unite his wing of the Confederate Army with that of General Stonewall Jackson. Ricketts, who was being flanked and in danger of being cut off, withdrew.

At the subsequent Battle of Antietam, James had two horses killed under him. He was badly injured when the second one fell on him. but not as severely as before. After two or three months’ confinement with Fanny’s loving care, he was in Washington, serving as President of a Military Commission, by the winter of 1862-63.

In the spring and summer of 1863, General Ricketts took part in the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and escaped personal injury, but his wife in gratitude for his preservation, nursed the wounded, and for months continued her labors of love among them.

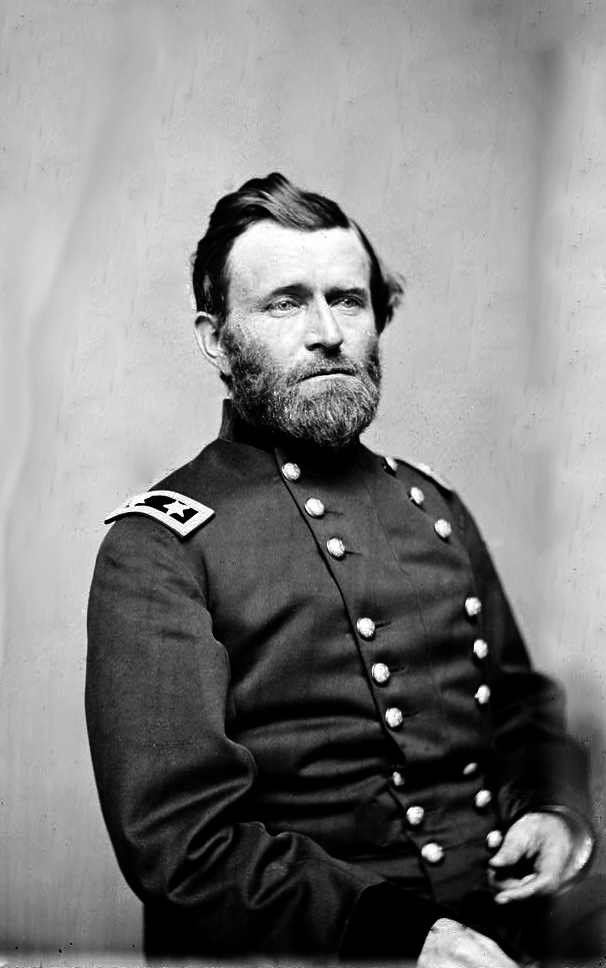

In March 1864, Ricketts was assigned to a division of John Sedgwick’s VI Corps, which he led through General Ulysses S. Grant‘s Overland Campaign in Virginia. The division performed poorly at the Battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. However, Ricketts received a promotion for “gallant and meritorious service” at the Battle of Cold Harbor on June 3, 1864, where he and his men fought bravely.

In July 1864, Ricketts’ command, numbering only 3350 men, was hurried north to oppose Jubal Early’s attack on Washington, DC. He fought at the Battle of Monocacy, suffering the heaviest losses while holding the Union left flank.

Ricketts served under General Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign. At the Battle of Cedar Creek, he commanded the VI Corps in the initial hours of the fighting, but was wounded by a Minie ball through his chest, and it was thought mortally wounded. Again for four months, Fanny watched patiently and tenderly over him until his recovery.

On March 13 1865, Ricketts was promoted to Major General, United States Army. In the closing scenes of the war, that culminated in General Robert E. Lee’s surrender, General Ricketts was once more in the field, and though suffering from his wounds, he did not leave his command until the war was virtually concluded.

His heroic wife Fanny remained at Union headquarters, watchful lest her husband should again be struck down again, but he was permitted to retire from the active ranks of the army, covered with scars honorably won.

In late July 1865, Ricketts was assigned to the command of a district in the Department of Virginia, a post he held until April 1866, when he was mustered out of the volunteer service. He was promoted again in July 1866, but declined the post. He retired from active service on January 3, 1867, and served on various courts-martial until January 1869.

Never in good health due to the chest wound he suffered in the Shenandoah Valley, James Ricketts lived with his wife in Washington, DC, until his death on September 27, 1887, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Fannie Lawrence Ricketts died on December 13, 1900, and was buried alongside her husband at Arlington.

SOURCES

James B. Ricketts

Women in the Civil War

Women on the Battlefield

Union Brigadier General James B. Ricketts