The Year: 1682

Image: William Penn’s 1682 treaty with the Lenape

Benjamin West Painting

In 1661, the year after Charles II was restored to the throne of England, William Penn was a seventeen-year-old student at Christ Church, Oxford. His father, a distinguished admiral in high favor at Court, had abandoned his erstwhile friends and had aided in restoring King Charles to the throne again.

Born to all the advantages of the landed aristocracy of England, Penn was sent to the finest English schools and on a grand tour of the continent by his father, Admiral Sir William Penn, conqueror of Jamaica.

Quaker Faith

While at a high church Oxford College, William Penn was surreptitiously attending the meetings and listening to the preaching of the despised and outlawed Quakers. There he first began to hear of the plans of a group of Quakers to found colonies on the Delaware River in America.

In 1667, William was converted at the age of 23 to the Quaker faith, and this gave new meaning and direction to the remaining 51 years of his life. His father at first disowned him, but later relented, and left him a considerable fortune. Penn’s outspoken support of Quakerism and opposition to the Church of England led to his imprisonment in the Tower of London in 1668-69, and twice in Newgate.

Colony of Pennsylvania

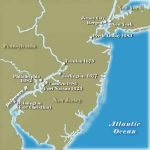

Because of his father’s service to the Crown, William Penn secured a charter from the king in 1681 for the land now included in the State of Delaware, and, with certain other Quakers, that of New Jersey as well. In addition, the Crown placed at the disposal of the Quakers 55,000 square miles of valuable territory, lacking only about three thousand square miles of being as large as England and Wales. Even when cut down to 45,000 square miles by a boundary dispute with Maryland, it was larger than Ireland.

William Penn founded the colony of Pennsylvania, and called it a Holy Experiment. He was the leader of a group of settlers called Quakers, who wanted Pennsylvania’s government to rule according to their religious truths. Though rooted in Christianity, the early Quakers taught that all people in the world, regardless of their religion, were illuminated by an inner light. They believed that this light was part of God, and that it would help guide a person to do what was right.

Government

Penn advertised for colonists, and began selling land at 100 pounds for five thousand acres, and annually thereafter a shilling quitrent for every hundred acres. He drew up a constitution – a frame of government, as he called it – after wide and earnest consultation with many. In the end, his constitution was very much like the most liberal government of the other English colonies in America. He had a council and an assembly, both elected by the people.

The council was very large, with seventy-two members, and had the sole right of proposing legislation, and the assembly could only accept or reject its proposals. This was a new idea, and it worked so badly in practice that in the end the province went to the opposite extreme, and had no council or upper house of the Legislature at all.

Pennsylvania, besides being the largest in area of the proprietary colonies, was also the most successful, not only from the proprietor’s point of view but also from the point of view of the inhabitants. The proprietorships in Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and the Carolinas were largely failures. Maryland was only partially successful; it was not particularly remunerative to its owner, and the Crown deprived him of his control of it for twenty years.

Penn, too, was deprived of the control of Pennsylvania by William III but for only about two years. Except for this brief interval (1692-1694), Penn and his sons after him held their province down to the time of the American Revolution in 1776, a period of ninety-four years.

Society, Schools, and Culture

Society in the middle colonies was far more varied, cosmopolitan, and tolerant than in New England. In many ways, Pennsylvania and Delaware owed their initial success to William Penn. Under his guidance, Pennsylvania functioned smoothly and grew rapidly. By 1685, its population was almost 9,000.

The heart of the colony was Philadelphia, a city soon to be known for its broad tree-shaded streets, substantial brick and stone houses, and busy docks. Though the Quakers dominated in Philadelphia, elsewhere in Pennsylvania others were well represented. Germans became the colony’s most skillful farmers. Important, too, were cottage industries such as weaving, shoemaking, cabinetmaking, and other crafts.

By the end of the colonial period, nearly a century later, 30,000 people lived there, representing many languages, creeds and trades. Their talent for successful business enterprise made the city one of the thriving centers of colonial America.

The first school in Pennsylvania was begun in 1683. It taught reading, writing, and keeping of accounts. Thereafter, in some fashion, every Quaker community provided for the elementary teaching of its children. More advanced training – in classical languages, history and literature – was offered at the Friends Public School, which still operates in Philadelphia as the William Penn Charter School. The school was free to the poor, but parents who could were required to pay tuition.

In Philadelphia, numerous private schools with no religious affiliation taught languages, mathematics and natural science; there were also night schools for adults. Women were not entirely overlooked, but their educational opportunities were limited to training in activities that could be conducted in the home. Private teachers instructed the daughters of prosperous Philadelphians in French, music, dancing, painting, singing, grammar, and sometimes bookkeeping.

Native Americans

Penn and the early Quakers insisted that the Lenape natives who lived in Pennsylvania be treated fairly, and for the next fifty years, there was peace between the white settlers and the Lenape. But when the French and English went to war, the Native Americans became caught in the middle and eventually sided with the French.

To end the war, the British signed treaties with the Lenape, promising protection and compensation for ancestral land. Unfortunately, those promises were not fulfilled once the war was over. In despair, the Native Americans tried to capture English posts and fought with the settlers. At times, Native Americans would even take settlers captive. In the early fall on 1764, English troops destroyed most of the remaining Lenape villages in Pennsylvania.

Holy Experiment

William Penn’s Holy Experiment would prove that religious liberty was not only right, but that agriculture, commerce, and all arts and refinements of life would flourish under it. He would break the delusion that prosperity and morals were possible only under one particular faith established by law.

He would prove that government could be carried on without war and without oaths, and that primitive Christianity could be maintained without a hireling ministry, without persecution, without ridiculous dogmas or ritual, sustained only by its own innate power and the inward light.

SOURCES

The Quaker Colonies

The Birth of Pennsylvania