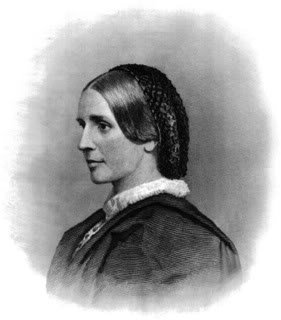

Civil War Nurse from Pennsylvania

At the outbreak of hostilities, Lydia Parrish was living at Media, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. Her husband, Dr. Joseph Parrish, was in charge of an institution for mental patients there. Lydia was one of the first women to volunteer her services on behalf of sick and wounded Union soldiers. She visited Washington, DC while the army was still in the area. Dr. Parrish had become connected with the newly organized U.S. Sanitary Commission, and Lydia worked with him and others examining the different forts, barracks, camps and hospitals then occupied by Union troops, in order to determine their condition.

At the outbreak of hostilities, Lydia Parrish was living at Media, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia. Her husband, Dr. Joseph Parrish, was in charge of an institution for mental patients there. Lydia was one of the first women to volunteer her services on behalf of sick and wounded Union soldiers. She visited Washington, DC while the army was still in the area. Dr. Parrish had become connected with the newly organized U.S. Sanitary Commission, and Lydia worked with him and others examining the different forts, barracks, camps and hospitals then occupied by Union troops, in order to determine their condition.

Hospital Work

On the first day of 1862, Lydia began working at the Georgetown Seminary Hospital. She wrote letters for the patients, read to them, and gave them all the aid and comfort in her power. She learned what their needs were and tried to find a way to provide them. She requested of the Sanitary Commission that she be allowed to draw from their ample supplies in order to fulfill the needs of the soldiers at the Georgetown hospital. They responded quickly, and authorized her to draw from their stores, and she was also promised aid and protection from the organization.

Both camps and hospitals were rapidly filling up. The weather was bad and the roads worse, but Lydia made occasional visits to the camps, and distributed clothing, books and comforts of various kinds. The “Berdan Sharpshooters” were encamped a few miles from the city, and needed immediate assistance. Lydia was requested by the Secretary of the Commission to “visit the camps, make observations, inquire into their needs, and report to the Commission.”

Lydia reached the camp through almost impassable roads, and was received by the officers with respect and consideration. She visited the men in hospitals and quarters, returned to Washington, and reported “two hundred sick, tents and streets needing police, smallpox breaking out, men discouraged, and officers unable to procure the necessary aid, that she had distributed a few jellies to the sick, checkerboards to a few of the tents, and made a requisition for supplies to meet the pressing want.”

But Lydia did not want to abandon her hospital service, and she noted in her diary that, “this outside work does not seem to be my mission. I have become thoroughly interested in my daily rounds at the city hospitals, particularly at Georgetown Seminary, where my heart and energies are fully enlisted.”

The stores of the Sanitary Commission were not then as ample as they later became, and the sick and wounded were in need of many things. Lydia decided to return home and try to interest the people of her neighborhood in the cause. She found the people ready to respond liberally to her appeals, and soon returned to Washington well satisfied with the success of her efforts.

She felt now that her time, and if need be her life, must be given to this work. After her brief absence, she returned to the Georgetown hospital. Some of her previous patients had died, but others whom she had left there welcomed her with enthusiasm as the “orange lady,” because she had been in the habit of distributing oranges to the men.

Ladies’ Aid Society

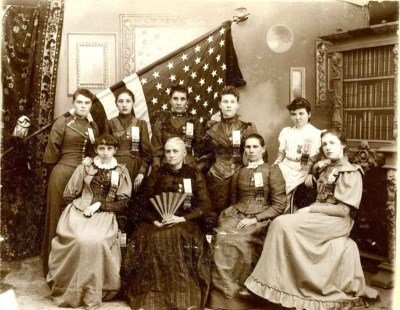

Family responsibilities called her home, and during her stay there she assisted in organizing a Ladies’ Aid Society at Chester, Pennsylvania. A hospital was about to be opened near Chester, and Lydia volunteered to prepare and furnish it. Sewing-circles were formed, and by the time the soldiers arrived, a plentiful supply of nice clothing was ready for them.

Lydia united with other women of the vicinity in organizing a corps of volunteer nurses. During the summer and autumn of 1862, she suffered a severe illness that continued for several weeks. After her health was restored, she went to Washington, and spent a few days in visiting the hospitals there.

She left for Falmouth, Virginia, on January 17, 1863. The army was in motion and much confusion existed, but they found comfortable quarters at the Lacy House, a large mansion there. There was a great deal of sickness among the troops. The weather was stormy, and though she underwent much privation for want of suitable food, she accomplished much good.

Later that year, she accompanied her husband and the Medical Director of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina on a tour of the hospitals at Yorktown, Fortress Monroe, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and New Bern, North Carolina.

For many months to come, as one of the managers of the women’s branch of the United States Sanitary Commission, Lydia helped organize the great Philadelphia Fair, which was held in July, 1864. The exhausting labors of those months, and the heat of the weather during the Fair, made it necessary for her to rest for the remainder of the summer.

Work with Prisoners of War

Later that year, Lydia accompanied her husband on a tour of inspection to the hospitals of Annapolis, and became interested in the condition of a group of returned prisoners of war, who needed so much done for them in the way of personal care. At the request of the medical officers and an agent of the Commission, she agreed to stay and work there.

What she saw, and what she did was written in the following letter that was published in the Bulletin of the United States Sanitary Commission:

Annapolis, December 1, 1864

The steamer Constitution arrived this morning with seven hundred and six men, one hundred and twenty-five of whom were sent immediately to hospitals, being too ill to enjoy more than the sight of their ‘promised land.’ Many indeed, were in a dying condition. Some had died a short time before the arrival of the boat.

Those who were able, proceeded to the high ground above the landing, and after being divided into battalions, each was conducted in turn to the Government store-house, under charge of Captain Davis, who furnished each man with a new suit of clothes and recorded his name, regiment and company. They then passed out to another building nearby, where warm water, soap, towels, brushes and combs awaited them.

After their ablutions [baths], they returned to the open space in front of the building, to look around and enjoy the realities of their new life. Here they were furnished with paper, envelopes, sharpened pencils, hymn-books and tracts from the Sanitary Commission, and sat down to communicate the glad news of their freedom to friends at home.

In about two hours, most of the men who were able had sealed their letters and deposited them in a large mail bag which was furnished, and they were soon sent on their way to hundreds of anxious kindred and friends.

Captain Davis very kindly invited me to accompany him to another building, to witness the administration of the food. Several cauldrons containing nice coffee, piles of new white bread, and stands covered with meat, met the eye. Three dealers were in attendance. The first gave to each soldier a loaf of bread, the second a slice of boiled meat, the third, dipping the new tin-cup from the hand of each, into the coffee cauldron, dealt out hot coffee; and how it was all received I am unable to describe.

The feeble ones reached out their emaciated hands to receive gladly, that which they were scarcely able to carry, and with brightening faces and grateful expressions went on their way. The stouter ones of the party, however, must have their jokes, and such expressions as the following passed freely among them: “No stockade about this bread,” ‘This is no confederate dodge,” etc.

One fellow, whose skin was nearly black from exposure, said, ‘That’s more bread than I’ve seen for two months.’ Another, “That settles a man’s plate.” A bright-eyed boy of eighteen, whose young spirit had not been completely crushed out in rebeldom, could not refrain from a hurrah, and cried out, “Hurrah for Uncle Sam, hurrah! No Confederacy about this bread.”

One poor feeble fellow, almost too faint to hold his loaded plate, muttered out, “Why, this looks as if we were going to live, there’s no grains of corn for a man to swallow whole in this loaf.” Thus the words of cheer and hope came from almost every tongue, as they received their rations and walked away, each with his “thank you, thank you” and sat down upon the ground, which forcibly reminded me of the Scripture account where the multitude sat down in companies, “and did eat and were filled.”

Ambulances came afterwards to take those who were unable to walk to Camp Parole, which is two miles distant. One poor man, who was making his way behind all the rest to reach the ambulance, thought it would leave him, and with a most anxious and pitiful expression, cried out, “Oh, wait for me!” I think I shall never forget his look of distress.

When he reached the wagon he was too feeble to step in, but Captain Davis, and Reverend J. A. Whitaker, Sanitary Commission agent, assisted him till he was placed by the side of his companions, who were not in much better condition than himself. When he was seated, he was so thankful, that he wept like a child, and those who stood by to aid him could do no less.

Soldiers—brave soldiers, officers and all, were moved to tears. That must be a sad discipline which not only wastes the manly form till the sign of humanity is nearly obliterated, but breaks the manly spirit till it is as tender as a child’s.

The Soldiers’ Friend

After returning to her home to make preparations for a longer visit to Annapolis, Lydia was again attacked by illness. After her recovery, knowing that an immense amount of ignorance existed among officers and men concerning the operations of the Sanitary Commission, she compiled a condensed statement of its plans and workings, together with a great amount of useful information in relation to the facilities in its system of special relief, giving a list of all Homes and Lodges, and telling how to secure back pay, bounties and pensions for soldiers.

The manuscript was submitted to the committee, accepted, and one hundred thousand copies ordered to be printed for distribution in all hospitals and camps. The Soldiers’ Friend, as it was called, was soon distributed in the different departments and posts of the army, and was even found in the Southern hospitals and prisons.

It was the pocket companion of men in the trenches, as well as of those in quarters and hospitals. Perhaps no work published by the Sanitary Commission has been of more real and practical use than this little volume, or has had so large a circulation.

It was the last public work performed for the Commission by Lydia Parrish. When the war ended, however, her work was not done. She simply transferred her efforts to helping the freedmen, still actively engaged in work growing directly out of the war.

SOURCE

Woman’s Work in the Civil War