The Year: 1664

New York best illustrates the great melting pot that would become America. By 1646, the population along the Hudson River included Dutch, French, Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, English, Scots, Irish, Germans, Poles, Bohemians, Portuguese and Italians.

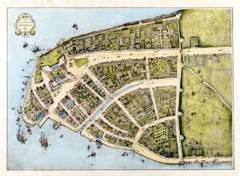

Image: Colonial New York on Manhattan Island

The English

In 1664, the English claimed New Netherland and renamed it New York, arguing that the Hudson Valley was part of Virginia as given by James I to two companies in 1606. This tract had been settled at both ends, they reasoned – on the James River and the New England coast – and why should a foreign power claim the central portion?

Richard Nicolls of the Royal Navy set out with a small fleet and about five hundred of the king’s veterans. Reaching New England, he enlisted several hundred militia from Connecticut and Long Island, and sailed for the mouth of the Hudson River.

Governor of New Netherland, Peter Stuyvesant had heard of the fleet’s arrival at Boston, but he was at Fort Orange (now Albany) when he was told that Nicolls was moving toward New Amsterdam. Stuyvesant made it to New Amsterdam one day in advance of the English fleet.

The Surrender

Upon arrival, Nicolls demanded the surrender of the fort. Stuyvesant refused. He swore and stamped his wooden leg, and tore to bits a conciliatory letter from Nicolls. He mustered his forces for defense, but the colonists didn’t cooperate. They were tired of his tyrannical government and of enriching a company at their own expense, forcing the old governor to yield.

The fort was surrendered without bloodshed, and Charles II gave the entire colony to his brother James, Duke of York, who named the colony New York. The upper Hudson also yielded, and Fort Orange became Albany, another of the duke’s titles. All of New Netherland, including the Delaware Valley, fell under English control.

In the Charter of 1664, the Duke of York has the power to establish laws, appoint officials, and make judiciary decisions that can only be appealed to the Privy Council in England. Eventually, the duke delegates many of his powers to his governors and establishes a Council that consists of important citizens who advise the governor.

At the time of the Nichols conquest, the little city of New Amsterdam at the southern tip of Manhattan Island contained some fifteen hundred people. The whole province of New Netherland was about ten thousand, one-third of whom were English. Nicolls became the first governor.

The rights of property, of citizenship, and of religious liberty had been guaranteed in the terms of capitulation. To these were added at a later date, equal taxation and trial by jury. In one year, Nicolls’ tact and energy had transformed the province into an English colony.

The people over whom Nicolls became governor in 1664 were composed of three separate communities, each different from the others in its government: the Dutch settlers on the Hudson River, the settlements on the Delaware River, and the English towns that had grown up under Dutch rule on Long Island.

In 1665, Governor Nicolls denies a request from English towns on Long Island for a general assembly, but establishes the Duke’s Laws, which include a system of local government that is eventually used by all of New York.

The Dutch continued to exercise an important social and economic influence on the New York region long after the fall of New Netherland and their integration into the British colonial system. Their gable roofs became a permanent part of the city’s architecture, and their merchants gave Manhattan much of its original commercial atmosphere.

Stuyvesant Again

It is interesting to note that after a journey to his homeland, Peter Stuyvesant returned to New York and made it his home in his old age. There on his farm, or bowery, as the Dutch called it, he spent a few quiet, happy years. A venerable figure was the aged Dutchman, and many who had hated him before now learned to love him.

He and Governor Nicolls became warm friends, and many a time they met and drank wine and told stories at each other’s tables. In 1672 this last of the Dutch governors died at the ripe age of eighty years, and his body was laid to rest at the little country church near his home – at a spot now in the heart of the city.

A short war between England and Holland followed, and the Dutch sailed up the Thames River and visited fearful punishment on the English, though they did not win back New York. Nine years later, the two nations were again at war, and a Dutch fleet re-conquered New York and the Hudson Valley. But the following year, a peace treaty ceded the colony back to the English, and Dutch rule ceased forever in North America.

William and Mary

If there was any bitterness against English rule, it was wholly removed in 1677 by an event of great importance to both hemispheres — the marriage of the leading Hollander of his times, the Prince of Orange, to the daughter of the Duke of York, the two afterward to become joint sovereigns of England as William and Mary.

The province of New York grew steadily to the time of the Revolution. By 1750, the population of the Province of New York was probably eighty thousand and this number was more than doubled by the opening years of the Revolution.

New York City was a busy market, with some twelve thousand people in 1750, and more than five hundred vessels plowed the waters that half surrounded it. The city was the political, social, and business center of the province. Among its leading residents in winter were the landholders of the Hudson Valley and Long Island, who spent their summers on their estates. But the great middle class, composed chiefly of tradesmen, made up the majority of the population.

New York declared its independence on July 9, 1776, becoming one of the original thirteen states of the Union. On April 20, 1777, New York’s first constitution was adopted.

SOURCES

Colonial New York

Colonial New York City