Colony of New Haven

Image: Quinnipiac Memorial Monument

Fort Wooster Park, New Haven, Connecticut

Monument to Native Americans

This monument to local Indians, whose ancient place names like Hammonasset and Wepawaug still identify the landscape, was dedicated on November 12, 2000. It stands above New Haven Harbor, looking down upon rich fishing and oystering grounds, and memorilizes the small tribe who educated the colonists in wilderness skills and helped protect them against raiding parties from larger tribes such as the Pequots.

The black granite stone has been etched with images of an Indian family walking with their dog toward the shore and a meeting with the unknown people aboard the ship coming in from the sea. The inscription reads:

A Quinnipiac Indian family walks to the harbor to meet the English newcomers as their way of life changes forever, April 24, 1638.

John Davenport, a London clergyman of an extreme Puritan type, Theophilus Eaton, a London merchant and a member of the Eastland Company, were the leaders of the colony, and many of their followers were men of considerable property.

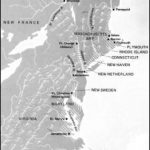

The company included men and women from London and others from Kent, Hereford, and Yorkshire. Both Davenport and Eaton were members of the Massachusetts Bay Company, and they were familiar with its work. On arriving in America in June, 1637, they stopped at Boston and remained there during the winter.

Pressure was brought on the newcomers to make Massachusetts their home, but Davenport was not content to remain where he would be only one among many. He sent Eaton voyaging to find a suitable place for worship and trade. Eaton suggested that Quinnipiac on the Connecticut shore would be perfect for their new settlement.

The Quinnipiacs

On April 24, 1638, five hundred English settlers arrived at the harbor to settle permanently on the lands of the Quinnipiac Native Americans. Dangerously weakened by disease, they welcomed the English as military allies. On November 24, 1638, the Quinnipiacs signed a treaty with Davenport and Eaton. The eastern side of the harbor was designated as a reserve for the Momauguin band. Ownership of the remaining lands was transferred to the English.

During the early years of New Haven, the Quinnipiacs traded deer meat to the colonists, who were unskilled in hunting. The Native Americans served as guides, traded canoes, and killed wolves that preyed on the colonists’ livestock. They taught the English how to clam and build weirs (dams) to catch fish.

The leaders of the Quinnipiacs were sachems—wise men and women who acted as civil or village chiefs. They exercised considerable influence as long as they were competent leaders and were not domineering. A sachem typically made important decisions only after consulting with his or her counselors, who were the older, respected members of the band.

Gimme Shelter

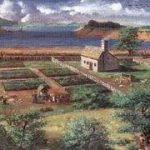

Description of the shelters that were first built by the colonists:

The temporary shelters, which the first planters of New England provided for their families till they could erect permanent dwellings, were of different kinds. Some planters carried tents with them to the place chosen for a new home; some built wigwams like those of the natives.

Either species would suffice in summer; but for winter they usually built huts, as they called them, similar to the modern log-cabins in the forests of the West, though in some instances if not in most, they were roofed, after the English fashion, with thatch. It was perhaps a peculiarity of New Haven, that cellars were used for temporary habitations. They were, as the name suggests, partially underground, and perhaps in most cases on a hillside.

The plantation covenant, like the compact signed in the cabin of the Mayflower, was a provisional arrangement of men, who, finding themselves beyond the actual jurisdiction of any earthly government, attempted to govern themselves according to the law of God. The first care of the planters was to choose a site for their future town; the next to lay out streets and house-lots, so that each family might as soon as possible make preparations for gardening and building.

Before winter most of the colonists who had arrived in April were living on their house-lots, leaving their cellars or other temporary shelters for new-comers. Some of the houses, being occupied by persons of small estates, were presumably such as a Dutch traveler saw at Plymouth, and describes as block-houses built of hewn logs.

From the mention of thatchers, and the precautions taken against fire, it may be inferred that these humbler tenements were roofed with thatch. Many of the houses, however, were of framed timber, and were covered with shingles or clapboards on the sides, and with shingles on the roof. Quinnipiac had a larger proportion of wealthy men than any other of the New England colonies.

Some of them, having been accustomed to live in large and elegant houses in London, expended liberally in providing- new homes. It was but natural that they should wish to maintain a style not much inferior to the style in which they had formerly lived; and as they confidently thought they were founding a commercial town in a country so rich in resources that on a single cargo exported to England they could afford to pay duties to the amount of three thousand pounds, they justified themselves in a liberal expenditure in building their houses.

Source: History of the Colony of New Haven, by Edward Atwater

Few of those that arrived intended to be part of a farming community. There was a substantial amount of money in the company, and this meant that they experienced few hardships. They colonists could buy what they needed. The location had been well chosen. There were to the east and west smaller harbors that would be good locations for settlement.

An Independent Colony

In June 1639, the colonists held a meeting in Robert Newman’s barn and declared that the Word of God should be their guide, and that only church members should take part in their government. They chose twelve men as their leaders. The church members elected Theophilus Eaton as their magistrate and four assistants, creating a form of government that was similar to that of the other New England colonies.

At a meeting of the General Court, a body of sixteen members under the leadership of Eaton, in September 1640, that the new harbor was officially referred to as New Haven. These leaders felt that in order for New Haven to become a new trading center they should create a series of settlements in the area. These towns would deliver their products to New Haven for export. The leaders of these communities would be members of the General Court, and would meet on a regular basis in New Haven.

Milford was established in 1639, Guilford in 1641. Stamford and Southold on Long Island were incorporated in 1641. The last member of this network, Branford, was settled in 1644. These five towns combined to form the New Haven Colony.

In 1660, there was a major change in the mother country. Charles II ascended the throne of England in 1660. Puritan power was over. Charles I had been condemned and beheaded in 1649 during Oliver Cromwell’s rule. Two of the judges who had signed Charles I’s death warrant escaped to New England in 1661. They took up refuge on West Rock at New Haven, in an outcropping of massive boulders.

It is believed, but not documented, that harboring these fugitives may have brought about the end of the independent New Haven Colony. The Connecticut Colony obtained a charter which included New Haven. After a two year argument, New Haven acquiesced. On January 5, 1665 an act of submission was passed by the General Court. The New Haven Colony officially became part of the Connecticut Colony.

SOURCES

New Haven

New Haven Colony

The Independent Colony

A New Look at Old New Haven

Colonists Meet the Quinnipiac Indians