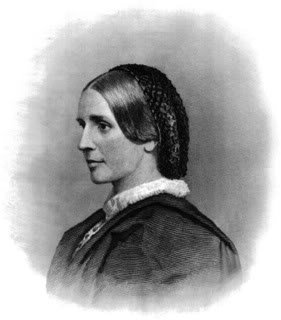

Emily Lyles was born in 1827 and grew up in the village of Spartanburg, South Carolina, until 1840, when the family moved to the country. Amos Lyles was determined to educate his only daughter, and he enrolled Emily in Phoebe Paine’s school in the village. Emily boarded there as well.

Miss Paine was a Yankee, and believed that women should be educated to their full potential, and she taught Emily to write with feeling and understanding about the world around her. Miss Paine also admonished Emily to never forget her innate talents.

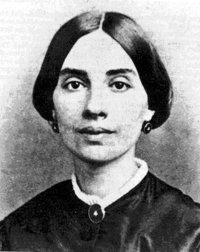

Emily married David Lyles in 1846. David farmed 100 acres of his 500-acre property, which was located 8 miles from Spartanburg, South Carolina. Thereafter, Emily’s life was tough. She gave birth to nine children, and lost a set of twins in infancy.

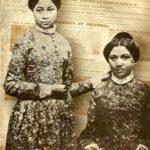

She raised her children, taught them, made and mended their clothes, provided food by tending a garden, cooked, and cleaned for her large family. At times, she had one slave to help her.

In 1860, Spartanburg County was an agricultural area with a gristmill, a sawmill, and a cotton gin. The population was 18,000, about half of which were slaves. The village of Spartanburg had about 1000 residents and a few stores, churches, and schools, and a couple of hotels.

When the Civil War began, her children were aged 21 months, four, six, eight, ten, twelve, and fourteen. In 1861, David left home and joined the Confederate Army. His 34-year-old wife was left to manage 7 children and 10 slaves as best she could.

David had kept a record of his farm work, hoping to discover the best time to plant his crops and do other tasks. He also wrote about current events and family life. When he left home, he asked Emily to continue keeping the journal. She made it her confidante and recorded her feelings, her opinions, and her fears.

The day after David left, Emily wrote in the diary for the first time:

How I shudder to think that I may never see him again. A load of responsibilities are resting upon me in his absence but I shall be found trying to bear them as well as I can.On November 24, 1862, she wrote:

Killing Hogs. This morning being cold and frosty, I had 8 of our hogs killed selecting for that purpose, according to my husband’s directions, the smallest and least promising…amounting to 1148 pounds and I missed my best friend very much indeed. Just after dark, to my unspeakable surprise he stepped in. It made us all very glad but his visit is only for a few days. He was sent home by the authorities to warn some laggard numbers to join their company.

November 25, 1862:

The Negro women are helping me do up the lard and sausages. The new ground was commenced a few days ago, and I hope the Negroes will be able to get on with it without their master. I have made into cloth this fall, about 65 lbs. of wool. Some jeans I have sold for $3.50 per yd.

December 2, 1862:

All going well as far as I can judge but tonight it is raining and cold and a soldier’s wife cannot be happy in bad weather or during a battle. All the afternoon as it clouded up I felt gloomy and sad and could not help watching the gate for a gray horse and its rider but he came not, though all his family are sheltered and comfortable the one who prepared the comforts is lying far away with scanty covering and poor shelter. ‘The soldier in his tent.’

No Civil War battles were fought in the county, and the only Union soldiers the citizens ever saw were pursuing Confederate President Jefferson Davis at the end of the war. But its citizens felt the effects of the conflict.

Spartanburg district was in a frenzy during the last few months of the war with news about Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s burning of Columbia. “I am nearly crazy,” Emily wrote of her fear that the Yankee army was marching on Spartanburg, but they never did.

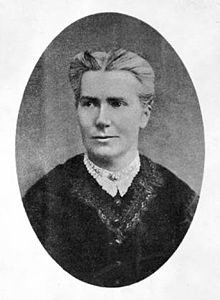

Shortly afterward, David returned safely and once again took up the journal. Emily resumed the duties of a 19th-century housewife. After her husband died in 1875 at age 54, Emily lived with her children until her death in 1899, from a stroke suffered while in a dentist’s chair.