First Woman Surgeon in the Union Army

After the Battle of Fredricksburg in December 1862, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker worked as a Civil War field surgeon near the Union front lines, treating soldiers in a tent hospital. She tried to increase the survival rate by advising stretcher bearers not to carry wounded soldiers downhill with the head below the feet. Although she probably did not perform any amputations, she thought that many of them were unnecessary and encouraged some soldiers to refuse them.

After the Battle of Fredricksburg in December 1862, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker worked as a Civil War field surgeon near the Union front lines, treating soldiers in a tent hospital. She tried to increase the survival rate by advising stretcher bearers not to carry wounded soldiers downhill with the head below the feet. Although she probably did not perform any amputations, she thought that many of them were unnecessary and encouraged some soldiers to refuse them.

Mary Edwards Walker, second female doctor in the United States, was born in Oswego, New York, on November 26, 1832, into an abolitionist family. Mary was the youngest of five girls, followed by one boy. Her father, Alvah, was a self-taught country doctor who believed strongly in equal rights and equal education for his five daughters. He intended for all of his children to be educated and to pursue professional careers.

Alvah also thought that women’s fashions of the day were too constrictive, even unhealthy, and discouraged his daughters from wearing them. Mary took his advice and adopted a style of wearing loose garments over a sort of trouser called ‘bloomers.’

Alvah built the town of Oswego’s first schoolhouse on his land, and all of his children were educated there. Mary and two of her older sisters graduated from Falley Seminary in Fulton, New York, and became teachers.

But early on, Mary had shown an interest in her father’s medical books, and she was encouraged to pursue that as a career. She taught school to earn enough money to pay her way through Syracuse Medical College, the first medical school in the United States to accept men and women equally.

She was the only woman in her class, and the second female doctor in the nation. After three 13-week semesters of medical training, in which she paid $55 per semester, Mary graduated in June 1855.

In 1856, she married a fellow medical school student, Albert Miller. During the wedding, she wore trousers and a man’s coat, and she kept her own name. They set up a joint practice in Rome, New York. The practice foundered—the public was not ready to accept a female doctor.

In the summer of 1860, Mary stayed with a family friend in Delhi, Iowa, hoping to secure a divorce (Iowa had more lenient laws). She returned to Rome, and they were divorced 13 years later.

In July 1861, after the Battle of Bull Run, Mary went to Washington, DC, to join the army as a medical officer. Her enlistment was denied, so she volunteered—serving as assistant surgeon at the hospital that had been set up in the US Patent Office. Her superior, Dr. J.N. Green, recommended that she be commissioned, but she never was.

As a volunteer, Mary could move about freely. She helped organize the Women’s Relief Association for the lodging of wives, mothers and children of the wounded soldiers in Washington. Sometimes, she took these families into her own home.

In 1862, Mary went to Forest Hall Prison in Georgetown, DC, but felt her services were not especially needed there, so she returned to New York. She earned a second medical degree from Hygeia Therapeutic College and by November returned to Washington.

In September 1863, Mary was finally appointed assistant surgeon in the Army of the Cumberland, and assigned to the 52nd Ohio Infantry based in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She worked as a field surgeon near the Union front lines after the Battle of Chickamauga, the first female surgeon in the United States Army.

The men were outraged. Dr. Perin, director of the medical staff, called it a ‘medical monstrosity’ and requested a review by an army medical board of Mary’s qualifications, doubting she knew much more than ‘most housewives.’

Mary dressed in a modified officer’s uniform, because of the demands of traveling with the soldiers and working in the field hospitals, but kept her hair long so that people would know she was a woman. She also carried two pistols at all times.

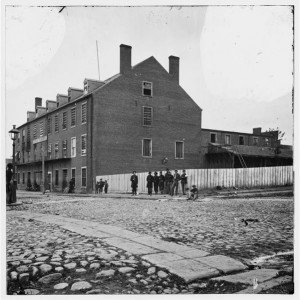

She was taken prisoner in April 1864 by Confederate troops while treating a Confederate soldier on the battlefield, and was imprisoned at Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia. She complained about the lack of grain and vegetables for the prisoners, and the Confederates added wheat bread and cabbage to the rations.

Four months later, she was exchanged with two dozen other Union doctors for 17 Confederate surgeons. She was proud that her exchange was for a Confederate surgeon with the rank of major. She was released back to the 52nd Ohio as a contract surgeon.

In October 1864, Mary was finally commissioned as acting assistant surgeon with a salary of $100 a month. She served six months caring for patients at the Louisville Women’s Prison Hospital and then finished out the war serving at an orphan asylum in Clarksville, Tennessee. She was discharged on June 15, 1865. For all her wartime service, Mary was paid a total of $766.16.

She had sustained an eye injury that led to partial muscular atrophy, which earned her a pension of $8.50 per month—less than some widows’ pensions. Believing her eye problem was temporary, Mary had refused an earlier offer of $25 a month.

As the problem intensified and interfered with her medical practice, she asked for $24 a month or a $100,000 lump sum. Her petition was rejected, but she was finally granted $20 a month.

Upon the recommendation of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman and General George Thomas, on November 11, 1865, President Andrew Johnson signed a bill to present Dr. Mary Edwards Walker with the Congressional Medal of Honor for Meritorious Service.

After the war, Mary Edwards Walker became a writer and lecturer, touring here and abroad on women’s rights, dress reform and health issues. In 1866, she was elected president of the National Dress Reform Association. She began to dress completely in men’s clothing, from top hat and bow tie to pants and shoes. She was proud of being arrested several times for ‘impersonating a man.’

In September 1866, Mary helped Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone organize the Women’s Suffrage Association of Ohio. She also coordinated activities for the Central Women’s Suffrage Bureau.

She worked for equal rights for women in all facets of life, from marriage to the workplace. She argued for the reform of divorce laws that placed women in desperate circumstances. She advocated women retaining their own surnames. She also authored two books devoted to her views on feminism.

She struggled on the brink of poverty as she lost work because of her refusal to conform to societal standards. She was ridiculed for many of her ideas and her assertive manner.

In 1890, Mary declared herself a candidate for Congress in Oswego. The next year, she campaigned for a U.S. Senate seat, and attended the Democratic National Convention.

Her militancy had caused most people, including her own family, to ostracize her. In 1917, while in Washington, Mary fell on the steps of the Capitol building. She was 85 years old and never fully recovered.

After the criteria for awarding such medals were revised, the Board of Medals officially revoked Mary’s Medal of Honor and asked her to return it. She reportedly said, “They can have it over my dead body.”

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker died on February 21, 1919, while staying at a neighbor’s home in Oswego. She was almost penniless.

In 1977, the Army Board, admitting that Dr. Walker had been a victim of sexual discrimination, restored the Medal of Honor to her, citing her for “distinguished gallantry, self-sacrifice, patriotism, dedication and unflinching loyalty to her country.”

In 2000, Mary Edwards Walker was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame at Seneca Falls, New York.