Virginia Teacher of Free Black Children

In the first half of the nineteenth century a number of slave rebellions occurred, which frightened white citizens and underscored the need to maintain tight control over the literacy of blacks. In June 1852 Margaret Douglass, a white former slaveholder from South Carolina, began a school for free black children in her home in Norfolk, Virginia. An unlikely martyr for black education, Douglass was arrested in May 1853 for violating the law – she had no idea that teaching any black child to read and write in Virginia was a crime.

In the first half of the nineteenth century a number of slave rebellions occurred, which frightened white citizens and underscored the need to maintain tight control over the literacy of blacks. In June 1852 Margaret Douglass, a white former slaveholder from South Carolina, began a school for free black children in her home in Norfolk, Virginia. An unlikely martyr for black education, Douglass was arrested in May 1853 for violating the law – she had no idea that teaching any black child to read and write in Virginia was a crime.

Margaret Douglass was born in Washington, DC, but her family moved to Charleston, South Carolina, when she was very young. She married and had raised two children there. In 1845, after the death of her son, Douglass moved with her daughter to Norfolk, Virginia, where she worked as a seamstress. Though very poor and without a husband to support her, she was also proud and independent.

In early 1852, Douglass stopped at a Norfolk barbershop to discuss some business with the proprietor, a free black man. She noticed two small black boys sitting in the back of the shop studying spelling books. The barber said they were his children and that “there was no one who took interest enough in little colored children to keep a day school for them.”

Douglass immediately offered to teach the barber’s five children how to read and write at no charge. The positive experience with these children encouraged Douglass to establish a school in her home a few months later. Douglass knew that it was illegal to teach slaves, and so she was careful to accept only free black children. In June 1852, Douglass opened her school with twenty-five boys and girls.

On the morning of May 9, 1853, two city constables came to the Douglass home and arrested Margaret for violating Virginia law. The officers marched the teacher and 25 frightened children to the mayor’s office, where Margaret was charged with “teaching colored children to read and to write.”

Douglass pleaded ignorance of the law, believing that it applied only to the teaching of slaves. She was appalled when the Mayor explained that teaching any black child was unlawful in Virginia. She told the mayor that she had no idea that it was illegal to teach free blacks, and the mayor dismissed the case.

However, the Grand Jury heard about the case and indicted Douglass anyway:

INDICTMENT COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, NORFOLK COUNTY,

In the Circuit Court. The Grand Jurors empanelled and sworn to inquire of offences committed in the body of the said County on their oath present, that Margaret Douglass being an evil disposed person, not having the fear of God before her eyes, but moved and instigated by the devil, wickedly, maliciously, and feloniously, on the fourth day of July, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and fifty-four, at Norfolk, in said County, did teach a certain black girl named Kate to read in the Bible, to the great displeasure of Almighty God, to the pernicious example of others in like case offending, contrary to the form of the statute in such case made and provided, and against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

On November 2, 1853, Douglass went to trial before Judge Richard Baker and a jury of twelve white men. She refused the services of a lawyer and defended herself.

After letting the prosecution present its case without opposition, Douglass rose and stated her case to the jury:

I am a strong advocate for the religious and moral instruction of the whole human family! Let us look into the situation of our colored population in the city of Norfolk for they are not dumb brutes. Think you, gentlemen, that there is not misery and distress among these people? Yes, indeed, misery enough, and frequently starvation. Even those that are called free are heavily taxed and their privileges greatly limited.

And when they are sick or in want on whom does the duty devolve to seek them and administer to their necessities? Does it fall on you, gentlemen? Oh, no, it is not expected that gentlemen will take the time to seek out a Negro hut for the purpose of alleviating the wretchedness he may find there. Why then prosecute your benevolent ladies for doing that which you yourselves have so long neglected?

But, if otherwise, there are your laws: enforce them to the letter. You may send me, if you so decide, to that cold and gloomy prison. I can be as happy there as I am in my quiet little home: and, in the pursuit of knowledge, and with the resources of a well-stored mind, I shall be, gentlemen, a sufficient companion for myself.

In her defense, she demonstrated that teaching free black children to read had been a common practice in the city’s Sunday schools for years, but the jury found Margaret Douglass guilty and affixed her punishment as a fine of one dollar.

In rendering judgement, Judge Baker spoke at length about the importance of religious instruction of blacks and its role in making slaves moral and happy, but stressed that it should be kept separate from “intellectual” instruction. He blamed this prohibition against black education on “abolition pamphlets and inflammatory documents” intended “to be distributed among our Southern Negroes to induce them them to cut our throats.”

Judge Baker ordered the sheriff to place Douglass in the prisoner’s box, and he meted out her sentence:

Margaret Douglass, stand up. You are guilty of one of the vilest crimes that ever disgraced society; and the jury have found you so. You have taught a slave girl to read in the Bible. No enlightened society can exist where such offences go unpunished. The Court, in your case, do not feel for you one solitary ray of sympathy, and they will inflict on you the utmost penalty of the law.

In any other civilized country you would have paid the forfeit of your crime with your life, and the Court have only to regret that such is not the law in this country. The sentence for your offense is that you be imprisoned one month in the county jail, and that you pay the costs of this prosecution. Sheriff, remove the prisoner to jail.

Margaret Douglass served her time without complaint, and when finished, she went home to her little house and her books.

Soon after her release, she and her daughter moved to Philadelphia in February 1854 where Douglass published an account of her Norfolk experience and lived “happy in the consciousness that it is here no crime to teach a poor little child, of any color, to read the Word of God.”

During the Civil War, the city of Norfolk fell to the Union Army in May 1862. Northern generals closed the city’s public schools to white children and opened them to blacks. At the close of the war, the city government regained control of the schools and returned them to the white community.

SOURCES

The Case of Mrs. Margaret Douglass

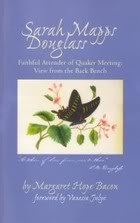

Margaret Douglass Taught Free Black Children to Read