Author, Feminist and Social Reformer

Frances Ellen Watkins was born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. She was not yet three years old when her mother died, and she was raised by her uncle, Reverend William Watkins, a teacher and radical advocate for civil rights who founded the William Watkins Academy for free African American children for Negro Youth ( where Frances was educated). The education she received there, and her uncle’s civil rights activism greatly influenced her writing.

Frances Ellen Watkins was born to free parents in Baltimore, Maryland in 1825. She was not yet three years old when her mother died, and she was raised by her uncle, Reverend William Watkins, a teacher and radical advocate for civil rights who founded the William Watkins Academy for free African American children for Negro Youth ( where Frances was educated). The education she received there, and her uncle’s civil rights activism greatly influenced her writing.

Frances attended her uncle’s school until she was thirteen years old, when she was sent out to earn a living. She found work as a babysitter and seamstress for the Armstrong family. Mr. Armstrong owned a bookstore, and he allowed Frances free access to books and encouraged her in her love for writing. Around 1846, Frances published her first collection of poetry, Forest Leaves. The book was extremely popular and over the next few years went through 20 editions.

In 1850, Frances Harper moved to Ohio to teach domestic science at Union Seminary in Columbus, the first woman to teach at that school. The principal of the school at the time was the Reverend John Brown, who later led the famous slave revolt at Harper’s Ferry. Her acceptance of the position was met with considerable protest.

In 1852, Harper took another teaching position in York, Pennsylvania. During this time, she lived in a house that was a station on the Underground Railroad, where she witnessed the movement of slaves toward freedom. While teaching there, she was greatly bothered by the sufferings of her people under the slave laws and decided to support the effort to abolish slavery.

Careers in Reform and Literature

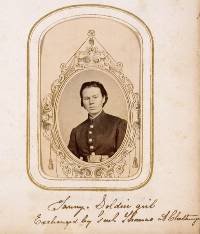

Harper quit her teaching job and began to support herself as a professional lecturer for the abolitionist cause, first for the Maine Antislavery Society. This marked the beginning of her activism. She began giving antislavery speeches throughout the northern United States and Canada – in an era when it was shocking for an unmarried young woman of any race to address mixed audiences of men and women.

In 1853, she joined the American Antislavery Society and became a traveling lecturer for that national organization. She was also a strong supporter of prohibition and woman’s suffrage. She often read her poetry at these public meetings, including the popular Bury Me in a Free Land.

A radical abolitionist, Harper preached and practiced the politics of Free Produce, urging economic boycotts of slave-produced goods. Denied appointment as an agent because of her gender, she collected donations for the Underground Railroad and forged friendships with Frederick Douglass, William Still, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. In her speeches, she included her own prose and poetry, which included the issues of racism, feminism and classism.

Greatly moved by Harriet Beecher Stowe‘s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harper published Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects in 1854, which included such antislavery poems as ‘The Slave Auction’ and ‘The Fugitive’s Wife.’ While traveling and lecturing, several thousand copies of her books were sold, and Harper donated a large portion of the proceeds to the Underground Railroad.

From 1854 to 1856, Harper traveled almost continuously in the eastern states. She published many of her essays written for the New York City Antislavery Society, the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and other organizations. For more than half a century, she involved herself in protest demonstrations against racial discrimination and used her experiences in her writing.

Harper’s The Two Offers appeared in the September-October 1859 issue of The Anglo-African Magazine, which advertised that it was ‘devoted to Literature, Science, Statistics, and the advancement of the cause of human freedom.’ In this short story, she showed that marriage is not the only option for intelligent women and that there are worse fates than becoming ‘an old maid.’

In 1860, Frances Watkins married Fenton Harper, a widower who lived in Cincinnati, Ohio. She gave birth to a daughter, Mary, in 1862. As a wife and mother, she felt compelled to retire from public life, but she never stopped writing and supporting various social reforms.

During the Civil War, Harper wrote prolifically, championing the cause of freedom. On May 23, 1864, her husband died, but she forged ahead. After the Emancipation Proclamation was enacted, Frances was in great demand as a speaker.

After the Civil War ended, she became increasingly vocal on feminist issues. She began touring again, giving lectures and publishing poetry in various antislavery publications. She formed alliances with strong figures in the feminist movement, including Susan. B. Anthony.

During the Reconstruction years, Harper began to fight for equality, education and civil rights. She appealed to women to use their time and talents to achieve “high and lofty goals.” She subsequently became the most widely published and recognized writer, before and after slavery.

She traveled through the Southern states under hazardous circumstances – going onto plantations, into the cabins of the freedmen, into churches, meetings and legislative halls – alone and unafraid, and unsustained by any society.

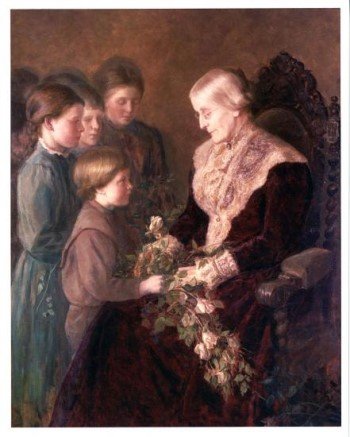

In 1866, Harper gave a moving speech at the National Women’s Rights Convention, demanding equal rights for everyone. Her efforts over the years to raise consciousness on this issue led to her election as Vice-President of the National Association of Colored Women in 1897.

Her first three novels were serialized in the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s paper, the Christian Recorder. Her body of work also includes several collections of poetry.

In 1892, Harper’s best known novel, Iola Leroy: or, Shadows Uplifted, was published. It is the story of a young woman striving to overcome racism during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The book tells of the heroine’s struggles: of being separated from her mother, her search for work and her experiences with racist boundaries in nineteenth-century society.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper continued her fight for freedom, equality, temperance and the rights of women in her lectures and writings until her death from heart disease in 1911 in Philadelphia.

At a meeting of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union held in Philadelphia in November 1922, her life’s works were recognized, and her name was placed on the Red Letter Calendar.

I ask no monument, proud and high,

To arrest the gaze of the passers-by;

All that my yearning spirit craves,

Is bury me not in a land of slaves.

~Bury Me in A Free Land