Novelist, Botanist and Educator

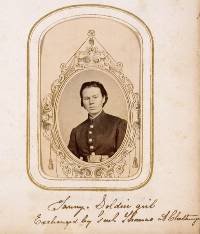

Eliza Frances Andrews (1840-1931) was a popular Southern writer whose works were published in popular newspapers and magazines, including the New York World and Godey’s Lady’s Book. Her longer works included The War-Time Journal of a Georgian Girl (1908) and two botany textbooks. Her passion was writing, but financial troubles forced her to take a teaching job after the deaths of her parents, though she continued to be published.

Eliza Frances Andrews (1840-1931) was a popular Southern writer whose works were published in popular newspapers and magazines, including the New York World and Godey’s Lady’s Book. Her longer works included The War-Time Journal of a Georgian Girl (1908) and two botany textbooks. Her passion was writing, but financial troubles forced her to take a teaching job after the deaths of her parents, though she continued to be published.

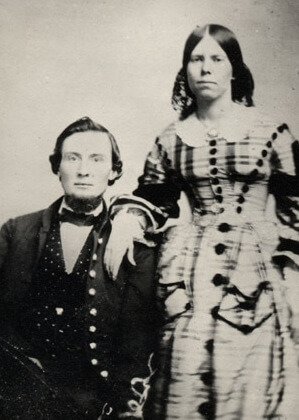

Eliza Frances Andrews was born in 1840 in Washington County, Georgia, the daughter of Judge Garnett and Annulet Ball Andrews. She became a writer and a teacher in the Civil War era. In the Andrews home, Eliza had access to newspapers, books, and magazines, and was encouraged to participate in discussions of political issues. Completing high school at LaGrange Female College in 1857, she remained at home and wrote for several newspapers.

In 1860, Washington, Georgia, about 75 miles east of Atlanta, was at the center of a prosperous plantation society that that grew tobacco and cotton. About two-thirds of its 2,200 inhabitants were Negroes, mostly slaves.

The town was awash with excitement on the night of January 19, 1861, when news came of Georgia’s secession from the Union. The citizens rung bells, fired guns, and gathered around the courthouse to raise a new Confederate emblem, a blue flag with a single five-pointed star.

The Andrews family were divided by the Civil War. Eliza and her sister-in-law made the flag referred to above, keeping it a secret from Judge Andrews, who was a staunch supporter of the Union. Eliza’s brother was the first man in the county to enter the Confederate Army.

No battles were fought within a hundred miles of Washington, Georgia, but the distress of war was often felt greatest by those who remained at home. At the time of Sherman’s march through Georgia, many citizens hid their silver, and drove their cattle into the thick forests along Kettle Creek.

In 1864, Eliza started her diary that would eventually be published as The War-Time Journal of a Georgia Girl. Historians consider her diary important for its insights into the experiences of elite Southern women during the Civil War.

Writing had become Eliza’s passion. Her first article for national publication was a political piece appearing in an 1865 edition of the New York World. She used only the initials of her first and middle names so it would be assumed that she was a male, because women writers were not taken seriously.

In early 1865, Eliza and her younger sister Metta traveled to their sister’s plantation in southwestern Georgia. Their sister’s husband was serving in the Confederate Army, and she was alone, except for the slaves that lived there.

After a three-month visit, 24-year-old Eliza and her younger sister prepared to return to their father’s home in Washington, Georgia.

On April 2, 1865, Eliza wrote:

Sunday – I went to church at Mt. Enon. After service, we stopped to tell everybody good-by, and I could hardly help crying, for we are to leave sure enough on Tuesday, and there is no telling what may happen before we come back; the Yankees may have put an end to our glorious old plantation life forever.

I went to the quarter after dinner and told the Negroes good-by. Poor things, I may never see any of them again, and even if I do, everything will be different. We all went to bed crying, sister, the children and servants.

Farewells are serious things in these times, when one never knows where or under what circumstances friends will meet again. I wish there was some way of getting to one place without leaving another where you want to be at the same time; some fourth dimension possibility, by which we might double our personality.

I have chosen a few excerpts from Eliza’s diary about the difficult days that followed the dissolution of the Confederate States of America. Life at home became difficult as Confederate soldiers on their way home streamed through the town:

May 1, 1865:

The conduct of a Texas regiment in the streets this afternoon gave us a sample of the chaos and general demoralization that may be expected to follow the breaking up of our government. They raised a riot about their rations, in which they were joined by all the disorderly elements among both soldiers and citizens. First they plundered the Commissary Department, and then turned loose on the quartermaster’s stores.

All of [Joseph E.] Johnston’s army and the greater portion of [Robert E.] Lee’s are still to pass through, and since the rioters have destroyed so much of the forage and provisions intended for their use, there will be great difficulty in feeding them. They did not stop at food, but helped themselves to all the horses and mules they needed. Our backyard and kitchen have been filled all day, as usual, with soldiers waiting to have their rations cooked.

May 2, 1865:

There is so much company and so much to do that even the servants hardly have time to eat. I never lived in such excitement and confusion in my life. Thousands of people pass through Washington every day, and our house is like a free hotel; father welcomes everybody as long as there is a square foot of vacant space under his roof.

Some of our friends pass on through without stopping to see us because they say they are too ragged and dirty to show themselves. Poor fellows! If they only knew how honorable rags and dirt are now, in our eyes, when endured in the service of their country.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis stopped in Washington on his way south. By that time his cabinet had begun to break up. Judah P. Benjamin had left Davis only a short time before, and upon arrival Stephen Mallory, Secretary of the Navy, left to attend the wants of his own family, after depositing his official papers with Eliza’s father.

May 3, 1865:

About noon the town was thrown into the wildest excitement by the arrival of President Davis. When he reined in his horse, all the staff who were present advanced to hold the reins and assist him to dismount.

The president’s arrival had become generally known, and people began flocking to see him, but he went to bed almost as soon as he got into the house. The party are all worn out and half-dead for sleep. They travel mostly at night, and have been in the saddle for three nights in succession.

Father went to call on the president, and in spite of his prejudice against everybody and everything to do with secession, Father says his manner was so calm and dignified that he could not help admiring the man. Crowds of people flock to see him, and nearly all were melted to tears.

May 5:

Porter Alexander [Artillery General in the Army of Northern Virginia, who was a native of Washington] has got home and brings discouraging reports of the state of feeling at the North. He says the generality of people were disposed to receive the Confederate officers kindly, but since the assassination the whole country is embittered against us—very unjustly too, for they have no right to lay upon innocent people the crazy deed of a madman.

The general belief is that Grant and the military men, even Sherman, are not anxious for the ugly job of hanging such a man as our president, and are quite willing to let him give them the slip, and get out of the country if he can. The military, who do the hard and cruel things in war, seem to be more merciful in peace than the politicians who stay at home and do the talking.

Unfortunately for Eliza and the rest of the Southern aristocracy, the Civil War destroyed her way of life and left her family destitute. Her mother and father died within seven years of the end of the war. She and her siblings were forced to sell the family plantation. As family finances became more strained, Eliza embarked on a career in education, first teaching at Washington Seminary in her hometown.

In 1872, she moved to Yazoo, Mississippi, where she taught and later served as school superintendent. Returning to Washington in 1874, she opened the Select School for Girls with a cousin, and later served as its principal.

In 1876, A Family Secret, her first novel, was published. It told the story of a woman struggling to maintain independence while also achieving artistic fulfillment, establishing a theme that would appear again in two later novels. It was a theme close to Eliza’s heart. A Mere Adventure, her second novel was published in 1879, followed three years later by her final novel, Prince Hal; or The Romance of a Rich Young Man.

In 1885, Eliza accepted a position at Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia, teaching literature and French. Toward the end of her decade-long tenure there, Eliza began to tour on the lecture circuit and frequently wrote for periodicals.

By 1900, she had returned again to Washington and began teaching high school science. She then turned her attention to one of her lifelong interests – botany. She spent a summer doing research at Johns Hopkins University. She published two botany textbooks, in 1903 and 1911, the second the result of six years of study in Alabama.

In 1926, she became the first American woman invited into the prestigious International Academy of Literature and Science in Italy. Due to age, she had to decline an invitation to address the Academy at Naples.

Eliza never married. She wrote in her diary early on that “marriage does not fit the path I have marked out for myself.” She escaped the traditional role for upper-class women through her ability to write and her determination to support herself, without becoming dependent on the men in her family.

Since the end of the Civil War, she had written four novels, two acclaimed botany texts, and dozens of articles and reports on topics ranging from politics to environmental issues.

Eliza Frances Andrews died in Rome, Georgia, on January 21, 1931, at the age of 90. She is buried in Resthaven Cemetery in her hometown of Washington, Georgia.