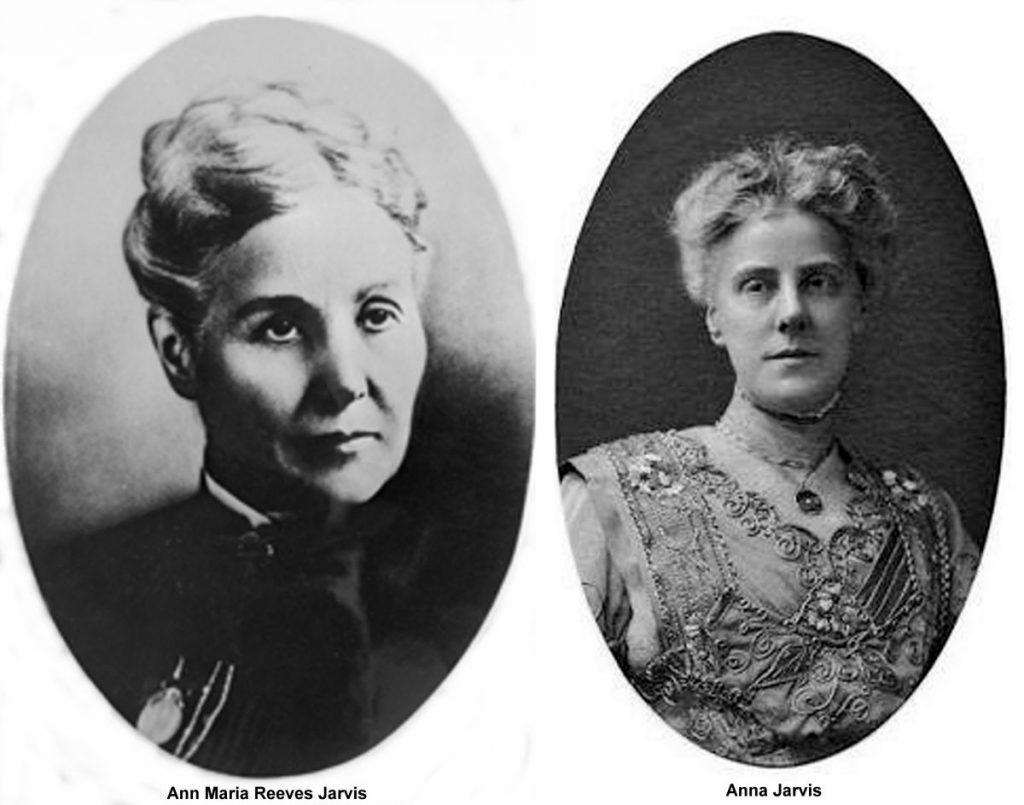

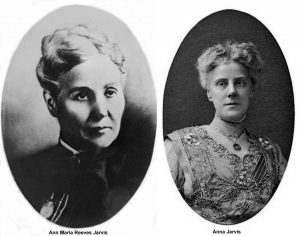

Ann Maria Reeves was born in Culpeper, Virginia, on September 30, 1832, the daughter of the Reverend Josiah Reeves. When Ann was 12 years old, the family moved to Barbour County in present-day West Virginia, when Reverend Reeves was transferred to a Methodist church in Philippi.

Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis and daughter Anna Jarvis

Two years later, Ann organized a series of Mothers’ Day Work Clubs in Webster and other nearby towns to improve health and sanitary conditions, which contributed to the high mortality rate of children in the area. She called on all women in Webster, Philippi, Pruntytown, Fetterman and Grafton to meet at local churches.

The clubs provided medicine for the indigent, hired women to work for families in which the mothers were ill and inspected bottled milk and food. Local doctors supported the formation of these clubs in other towns.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad made Taylor County a strategic site during the Civil War. In 1861, both Union and the Confederate officials ordered the local troops to hold the railroad at Grafton at all costs.

Ann quickly sensed a possible disruption in the clubs. She called an urgent meeting and announced her objectives:

To make a sworn-to agreement between members that friendship and good will should obtain in the clubs for the duration and aftermath of the war. That all efforts to divide the churches and lodges should not only be frowned upon but prevented. We are composed of both the Blue and the Gray.

She urged the Mothers’ Day Work Clubs to provide relief to Yankee and Rebel soldiers in the area, which was done, thus preserving an element of peace in a community that was being torn apart by political differences.

For the remainder of the Civil War, Ann Jarvis worked tirelessly despite the personal tragedy of losing four of her children to disease. Near the end of the war, the Jarvis family moved to the larger town of Grafton.

Tensions increased as Union and Confederate soldiers returned home after the war. In the summer of 1865, Ann organized a Mothers’ Friendship Day to bring together soldiers and neighbors of all political beliefs. The event was a great success despite the fear of many that it would erupt in violence. Mothers’ Friendship Day was an annual event for several years.

Under Granville Jarvis’ leadership, the Andrews Methodist Church was built in Grafton and dedicated in 1873. Ann taught Sunday School at the church for the next twenty-five years. After his death in 1902, she moved to Philadelphia to live with her son Claude, and daughters Anna and Lillian.

Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis died in Bala-Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, on May 9, 1905, at the age of 72. On the day she was buried, the bell of Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton was tolled seventy-two times in her honor.

Ann’s daughter, Anna Jarvis, held a memorial to her mother on the anniversary of her death in May 1906. She praised the outstanding accomplishments her mother had made through the Mothers’ Day Work Clubs she had established before the Civil War.

Miss Jarvis employed every means available to establish Mother’s Day as a national holiday. She wrote hundreds of letters to legislators, executives and businessmen. She was a fluent speaker and seized every opportunity to promote her project.

Her first real break came from merchant and philanthropist, John Wanamaker of Philadelphia. With his support, the movement gained momentum. On May 10, 1908, the first Mother’s Day ceremonies were held at the Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton and in the Wanamaker Store Auditorium in Philadelphia.

In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson signed a resolution proclaiming Mother’s Day a national holiday to be celebrated on the second Sunday in May.

During the 1920s, Anna Jarvis soured on the holiday, because it became so commercialized. According to her New York Times obituary, Jarvis became embittered because too many people sent their mothers a printed greeting card. She considered it “a poor excuse for the letter you are too lazy to write.”

Anna Jarvis and her sister Ellsinore spent their family inheritance campaigning against the holiday. Both died in poverty.