One of the First Feminists in the United States

Abby Kelley (1811–1887) was a Quaker abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Slavery Society. Fighting for equal rights for women soon became a new priority for many ultra abolitionists and Kelley was among them, speaking on women’s rights in Seneca Falls, New York five years before the first Women’s Rights Convention would be held there.

Abby Kelley (1811–1887) was a Quaker abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Slavery Society. Fighting for equal rights for women soon became a new priority for many ultra abolitionists and Kelley was among them, speaking on women’s rights in Seneca Falls, New York five years before the first Women’s Rights Convention would be held there.

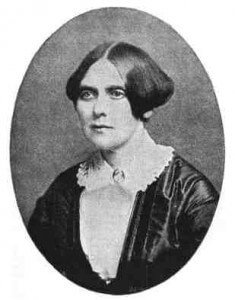

Image: Abby Kelley

Charlotte Wharton, Artist

Abigail Kelley was born on January 15, 1811, in Pelham, Massachusetts. She was quite delicate as a child, and her family encouraged her to spend time outdoors. She helped her father around the farm, climbed trees, and became quite the little tomboy.

Abby was raised as a Quaker, learned the Bible at an early age, and used the terms ‘thee’ and ‘thou.’ In 1826, she was sent to the New England Friends Boarding School. Then she worked as a teacher for a few years.

She began to read William Lloyd Garrison’s paper, the Liberator, and became a devoted abolitionist. She was elected secretary of the Lynn Female Anti-Slavery Society, and she was one of the founding members of the New England Non-Resistant Society, which supported nonviolent social reform.

At a time when society demanded that women be silent, submissive, and obedient, Abby was vocal, assertive, and headstrong. Despite harassment and ridicule, she never compromised her belief that all people are created equal and deserve to be free.

Her career as a lecturer began in 1838, when she gave her first speech for the American Anti-Slavery Society to an audience of men and women at Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia. She would go on to become one of its most popular speakers and its most successful fundraiser. Through her influence, many women became abolitionists and supporters of women’s rights.

Frederick Douglass, a slave who escaped to freedom and fought to free his people from bondage, sometimes joined Abby on the lecture tours. She liked to work with black speakers, who could give firsthand accounts of the horrors of slavery.

Douglass wrote about Abby: “Her youth and simple Quaker beauty, combined with her wonderful earnestness, her large knowledge and great logical power bore down all opposition wherever she spoke, though she was pelted with foul eggs and no less foul words from the noisy mobs which attended us.”

Abby went to Seneca Falls, New York, in 1843 to give an abolitionist lecture, and initiated a chain of events that founded a congregation and a host for the First Women’s Rights Convention five years later.

In 1845, Abby received a request from the Ohio American Anti-slavery Society, asking her to attend the annual meeting of the society and to present their program at conventions throughout Ohio during the summer.

On June 5, Abby arrived at the annual meeting, which was held in the New Lisbon Disciples’ Church. She lectured to an audience of 500 people, mostly Quakers and blacks, who filled the church to overflowing. Many people had to be content with sitting on benches outside.

Even those opposed to abolition of slavery often spoke of Abby’s beauty and her power as a speaker. In May of 1845, the New York Herald an anti-reform newspaper, praised her address at an American Anti-Slavery Society meeting, and described her as “the lovely, intellectual, enchanting, fascinating Abby Kelley.”

In the summer of 1845, Abby attended an annual Quaker meeting at Mount Pleasant, Ohio. These were not abolitionist Friends, but Orthodox Quakers. Abby waited for most of the day before speaking. She had hardly begun her lecture when she was ordered to stop disturbing the meeting. She tried to go on, but the men physically carried her out of the building.

After a four-year courtship, Abby and fellow abolitionist Stephen Foster married in December 1845. In addition to his antislavery stance, Stephen also advocated women’s rights, world peace, and labor reform.

Abby returned to lecture in Ohio the following summer, but the need was so great that she stayed for 18 months. At the request of anti-slavery people, she sent for Stephen to join her, and they lectured together. During 1845 and 1846, they visited every major city in the state.

Abby’s health suffered from the grueling schedule of lecturing during the day and traveling to another location by night for the next day’s speaking engagement. Fatigue was her constant companion. She was so overwhelmed with the urgent need of the enslaved that she drove herself unmercifully.

When at last she and Stephen were about to leave Ohio, she was amazed to discover that she was pregnant. They immediately returned to Massachusetts. The farm that Stephen had bought in Worcester needed a lot of work, but he loved working with his hands. He had grown up on a farm and had learned carpentry as a young man, so he already possessed the skills needed to run the farm and to improve the dilapidated farmhouse on the property.

He set to work on the house and soon transformed it into an attractive and comfortable residence for his family. The fields were soon so productive, and the trees in the orchards so plentiful that Stephen was kept busy selling vegetables, milk and fruit. And their home became a station on the Underground Railroad.

The Fosters’ only child, Paulina, was born May 19, 1847. They called her Alla. For a few years, neither did much public speaking. But by 1850, both of them had returned to the anti-slavery lecture circuit, and Abby had also taken up the cause of women’s rights. Far ahead of her time, she insisted that a woman could enjoy a family and an active life outside the home.

In 1850, Abby was one of many abolitionists who supported the first national women’s rights convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. The ideals of freedom for slaves applied equally to the new women’s reform movement. Early women’s rights activists used the existing abolitionist networks for support. Abby became more active in the women’s movement after the Civil War.

Abby believed that the problem of slavery was a moral one, and that only moral weapons would free the slaves. During the Civil War, she predicted that if the slaves were freed for the sole purpose of preserving the Union that hatred of the black race would continue. Despite health difficulties, she remained a radical even after abolition.

Abby’s daughter, Alla, an intelligent and responsible girl, suffered from curvature of the spine. When she was 11 years old, the disease attacked her body so severely that she became an invalid. But with the use of surgical corsets and other measures, she slowly improved. Through these many months, Abby never left her side.

At the age of 21, Alla attended Vassar College in New York, a college that offered a classical and a scientific education. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1872, and continued her education at Cornell University for a year, studying history. She was one of the first women to enroll in the school, which had opened in 1868.

While writing her dissertation, Alla taught high school. In 1876, she earned a Master of Arts degree from Cornell, and continued teaching. She also represented her parents at women’s rights events.

Abby always struggled to balance her anti-slavery and women’s rights work with her role as a wife and a mother. She devoted over 50 years of her life to fight for the rights of all humanity. Although too ill to travel in later years, Abby and Stephen weren’t quite finished yet. They protested Abby’s inability to vote by refusing to pay their property taxes.

Stephen died in 1881, after suffering a paralytic stroke. Abby Kelley Foster died at Worcester, Massachusetts, on January 14, 1887, the day before her 76th birthday.

My favorite Abby quote: “Bloody feet, Sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you come hither.”