Confederate Spy in the Civil War

Antonia Ford was a Confederate spy credited with providing the military information during the First Battle of Manassas (1861), and during the two years following. In 1863 Ford was accused of spying for John Singleton Mosby after his partisan rangers captured Union general Edwin Stoughton in his headquarters. Mosby denied that Ford ever spied for him, but she was arrested and incarcerated at Old Capitol Prison.

Antonia Ford was born in Fairfax, Virginia, in 1838, daughter of prominent merchant and secessionist, Edward R. Ford. Antonia was living a life of quiet comfort when the Civil War began. She was 23 years old and unmarried. Their home was located across the road from the Fairfax Court House.

Antonia’s brother Charles served as a lieutenant in General J.E.B. Stuart‘s Horse Artillery, before losing his life at the Battle of Brandy Station. The family was good friends with General Stuart and his scout, Colonel John Singleton Mosby. In the early part of the War, Stuart’s cavalry were in the vicinity of Fairfax, and he visited the Ford family frequently.

When the Army of the Potomac moved out of Washington, DC, in June 1861 on its way to what would become the First Battle of Bull Run, its path led through Fairfax. After a skirmish, Southern forces evacuated the town, and the Union troops occupied it. The Ford home became a boarding house for Union officers,

Antonia, whom contemporaries described as beautiful and refined, obtained valuable information from Union officers who were staying in her home. She listened to conversations and reported what she heard to Stuart’s troops located near Fairfax Court House.

By the fall of 1861, Ford’s patriotism and loyalty had endeared her to J.E.B. Stuart, already a well-respected general in the Confederate cavalry because of his courageous performance in leading a crucial charge on the federal forces at First Bull Run.

On October 7, 1861, Stuart commissioned Antonia as an honorary member of his staff. She hid the citation under her mattress. “She will,” Stuart wrote, “be obeyed, respected and admired by all the lovers of a noble nature.”

One Confederate soldier who witnessed Stuart’s presentation of the commission to Ford later insisted that the document bore the impression of the General’s signet ring. Still, he noted that General Stuart’s intentions were more lighthearted than serious, and the document was presented to Antonia with only “mock formality.”

In August 1862, just before the Second Battle of Bull Run, Antonia rode 20 miles by carriage in the rain in order to warn Stuart about a Union plan to use the Confederate colors to draw the soldiers away from their assigned positions.

In December 1862, when Union General Edwin Stoughton set up headquarters at Fairfax, Antonia relayed information about the Federals’ movements to Stuart and Mosby. In the early months of 1863, to fortify the federal capital, Union authorities sent more troops to Fairfax, still under the command of Stoughton.

Mosby, a talented Confederate cavalryman, harassed the enemy in his usual style, with raids and assaults on their camps. General Ulysses S. Grant would later order him hanged without trial if captured, but they never caught him.

Antonia seems to have cultivated a friendly relationship with General Stoughton. They went riding through the countryside together so often that their relationship became the source of gossip and concern among the general’s own troops.

On March 8, 1863, General Stoughton hosted a party for his mother and sister, who had come down from Vermont to visit him. The party was held at the Ford residence, where the two women were staying. It was a rainy and windy night, but the soiree was a great success. By 1 a.m. the last carriage of guests departed, and everyone went to bed.

A little after 2 a.m. Colonel John S. Mosby and two dozen raiders slipped into Fairfax. Sgt. James “Big Yankee” Ames had defected from the 5th New York Cavalry to serve with Mosby. He was very knowledgeable about the Union encampments in the area and served as their guide.

They were wearing Federal issue gum ponchos to protect them from the rain, and they managed to pass through the drowsy pickets unchallenged. An advanced guard had captured the only sentry on duty and the telegrapher.

Mosby and five men went to the residence of Dr. William Gunnell, a few hundred yards north of the courthouse, where General Stoughton’s headquarters was located. They banged on the front door, announcing loudly that they had an important dispatch for the General.

One of the general’s staff answered the door and was greeted by Mosby and a Colt revolver. Under gunpoint, the soldier led the Rebels to Stoughton’s bedroom. The general was sleeping soundly after the evening’s festivities, and there were champagne bottles on the bedside table.

Mosby pulled the covers off Stoughton. The groggy general demanded to know what was going on. In one of his audacious bluffs, Mosby told Stoughton that the Confederate cavalry under General Stuart had surrounded the courthouse.

Stoughton had been a West Point classmate of Fitzhugh Lee, nephew of General Robert E. Lee, and he asked to be brought to his old friend, and Mosby agreed. But Lee was with Stuart’s cavalry miles away in Culpeper.

They set out at 3:30 am, just in time to get through the federal lines before daybreak. A few of the prisoners managed to escape along the way, but Mosby had pulled off a spectacular feat, capturing a brigadier general, two captains, 30 prisoners and 58 horses without one shot being fired!

At Culpeper, Mosby handed Stoughton over to his classmate, Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, who was rude to Mosby and apologized to Stoughton. “He was very polite to his old classmate,” Mosby wrote in his memoirs, “but he treated me with indifference, did not ask me to take a seat by the fire, nor seem to be impressed by what I had done.”

The reaction of the Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was intense. He instructed Lafayette Baker, the head of the United States Secret Service, to conduct an investigation of the circumstances and to arrest those responsible.

The Federals did not know about the deserter in Mosby’s command, and their attention quickly focused on prominent local secessionists. Edward Ford and several other citizens were arrested on March 9, but he was soon released. Suspicion then fell on his daughter, Antonia.

Lafayette Baker was convinced that a spy was working in the area. “The time, circumstances, and mode of this attack and surprise,” he reported, “the positive and accurate knowledge in possession of the rebel leader, of the numbers and position of our forces, of the exact localities of officers’ quarters, and depots of Government property, all pointed unmistakably to the existence of traitors and spies within our lines, and their recent communication with Confederate officers.”

Acting on his suspicions, Baker sent a female agent, Frankie Abel, to the Ford home. Abel posed as a refugee from Union-occupied New Orleans. She went dressed in faded calico and looked as poor as a church mouse. The Fords took her in, gave her stylish clothes to wear, and a place to stay.

Abel befriended Antonia, who made the mistake of showing her the commendation she had received from General Stuart. That document, to Lafayette Baker, was sufficient proof of her treasonable activities, though Mosby and Stuart vehemently denied that Antonia had played any part in the general’s kidnapping.

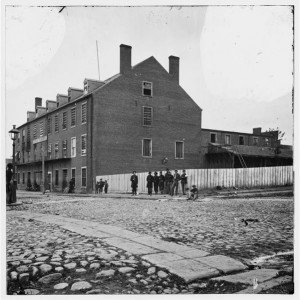

After Abel left the Ford home, Baker immediately ordered Ford’s arrest and transfer to Washington DC, about fifteen miles to the northeast. On March 16, she was searched and found in possession of contraband correspondence and a handful of Confederate money. Baker took those items from her and ordered her into confinement in the Old Capitol Prison, a dingy damp place resembling a medieval dungeon.

Word of Antonia’s arrest spread quickly. The New York Times condemned her without a trial. “Miss Ford of Fairfax,” one article said, “was unquestionably the local spy and actual guide of Captain Mosby in his late swoop upon that village.”

Union Major Joseph Willard had been a provost marshal at Fairfax, and had fallen in love with Antonia while he was there. He had himself transferred to duty in Washington, and worked diligently for her release from prison.

Antonia’s health, already frail, was failing from the poor diet and exposure she received in prison. After seven months, Joseph finally persuaded her to sign a loyalty oath to the Union and arranged for her release. He proposed and they were married on March 10, 1864, almost exactly a year after General Stoughton’s kidnapping.

Joseph resigned his Army commission, and the couple settled in Washington, DC, where his family owned the famous Willard Hotel. Antonia gave birth to three children, two of whom died in infancy, and she never fully recovered her health.

At the age of 33, after only seven years of marriage, Antonia Ford Willard passed away in 1871 and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, DC. Many were convinced that her untimely death was a direct result of her confinement in the Old Capitol Prison.

Joseph never remarried and died a recluse in 1897.

What sad endings to such promising lives.