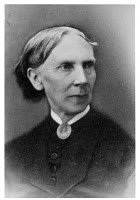

Civil War Nurse and Educator

Amy Morris Bradley, a schoolteacher from Vassalborough, Maine, abhorred the limitations placed on women in the 19th century. She started out as a field nurse for the Union Army, then became an agent for the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She also served aboard hospital ships and ran a Soldiers’ Home in Washington, DC.

When the Civil War erupted, Bradley quickly volunteered her services as a nurse. She was assigned to the Fifth Maine Infantry but soon transferred to a hospital ship on the James River in Virginia. At that time, nursing was viewed as domestic work. Bradley’s abilities led her to the United States Sanitary Commission where she rose through the ranks to become Special Relief Agent. In that capacity she transformed makeshift army hospitals from unsanitary camps into clean, efficiently-run hospitals.

Social norms during the Civil War era were not kind to women who exposed themselves to the horrors of war by working in hospitals. Whether black or white, Southern or Northern, nurse or laundress, the women who worked in military hospitals – more than 20,000 of them – had to deal with the intoxication of surgeons, the contempt of generals and the challenge of dealing with filth, lack of supplies, mosquitoes and bad weather. Bradley’s success earned her the respect of influential military and political leaders.

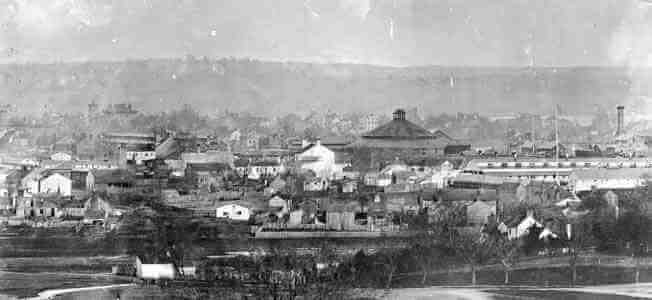

In 1865, a group of prominent Boston Unitarians formed a philanthropic organization, the Soldiers’ Memorial Society, which proposed to establish free schools for poor children in the city of Wilmington, North Carolina. The city, a port on the Cape Fear River, had received a great deal of attention in Sanitary Commission reports following the fall of Fort Fisher in January 1865. Bradley offered her services to the group, and was appointed to serve as the official SMS agent in Wilmington.

After Christmas 1866, Bradley set out from Boston on a railroad journey south. Upon reaching Weldon, Virginia, she set out on the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, which had once served as the lifeline to the Army of Northern Virginia.

Bradley arrived in Wilmington before dawn on December 30, 1866. She met with the Reverend S. S. Ashley, a New Englander who represented the interests of the American Missionary Society and the Freedmen’s Bureau. Their conference was followed by a tour of Dry Pond, one of the city’s poorest white neighborhoods.

Bradley soon became a familiar Wilmington figure as she went from house to house to drum up interest in her proposed school. Though some women pulled their skirts aside when she passed, or spat upon her, she held her head high and continued her rounds.

In January 1867, Silas Martin provided her with a key to the Dry Pond Union Schoolhouse. Martin and others had established it as a free school before the Civil War, but it had been abandoned in 1862. Four days later, Bradley welcomed three pupils to the school.

After only two months in Wilmington it was obvious that she had managed the impossible. The school had as many students as it could hold and there was a long waiting list. She wrote in her report:

I have a day school of seventy-pupils thoroughly organized and classified; an industrial-school of thirty-three, and a Sunday school. We have received a present from thirty-four gentlemen of this city of $99.50, which has made it possible to place in the hands of our pupils all needed books, besides purchasing a magnetic globe, and making improvements in our classroom.

The grateful teacher paid to have a card of thanks printed in the Wilmington Journal.

On the following day the Dispatch ran a front page article that made it clear that Miss Bradley was not welcome in Wilmington:

Equally obnoxious and pernicious is to have Yankee teachers in our midst, forming the minds and shaping the instincts of our youth – alienating them, in fact, from the principals of their fathers, and sewing the seed of their poisonous doctrine upon the unfurrowed soil. The South has heretofore been free from puritanical schisms and isms of New England, and we regret to see the slightest indication of the establishment here of a foothold by their societies.

But by mid-summer, Bradley had received financing for a new school. Wilmington citizens gave her $1000 to purchase land for the new building, which would be named the Hemenway School, to honor Mary Porter Tileston Hemenway who donated $1000. The Freedmen’s Bureau added $1,804.45 for construction, and the Peabody Fund contributed $1500 for teacher salaries.

In early November 1868, the old Union School opened with 223 pupils and three teachers. Bradley opened the Hemenway School to 157 students on December 1, 1868. On January 1, 1869, the Pioneer School in Masonboro Sound opened with 45 students.

In two short years, Miss Bradley’s enterprise had grown from a one-teacher, three-pupil school to a complete school system with eight instructors, 435 students, and three buildings.

In Wilmington, Amy Morris Bradley had again broke with convention and founded what is now known as the public school system. Her simple headstone in Wilmington’s Oakdale Cemetery reads “Our School Mother.”