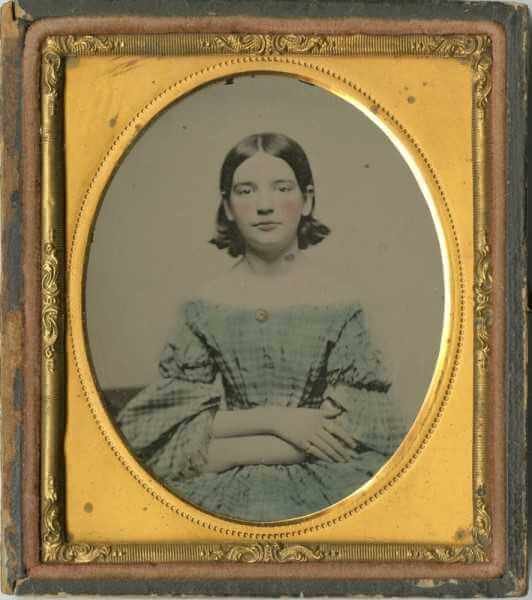

Union Nurse from Illinois

A Civil War nurse, her birth name was Eliza Atherton. She was born on March 24, 1817 in the town of Auburn, New York. Her maternal grandfather was John Ward who was related to General Artemus Ward, a leader of the American Revolution.

In March of 1826, Lizzie’s paternal grandfather, Jonathan Atherton of Cavendish, Vermont, died. He left his large farm to Lizzie’s father, Stedman Atherton, with the understanding that he would make it his home and care for his mother for the balance of her life. In October of that year, Stedman moved to Cavendish with his wife and two little girls. Lizzie was nine years old.

This was a great change from living in town. The farm was quite large. It had many orchards, pastures for hundreds of sheep and broad fields of grain. The house stood on a hill, and the lawns surrounding it were filled with lush flower gardens.

Grandmother Atherton was a petite English woman. She ruled the house and the farm with an iron fist. She was proud that her house was kept perfectly clean and neat at all times. Almost everything that was needed on the farm was manufactured on the farm. She was horrified to learn that Lizzie’s mother did not know how to spin or weave or gather food and preserve it for the winter.

The senior Mrs. Atherton thought Lizzie was a spoiled child, and she took it upon herself to train the girl. Lizzie was sensitive, and Grandmother’s constant scolding affected her greatly. Lizzie could hardly eat if her grandmother was glaring at her, and she cried frequently.

Lizzie and her mother drew closer together than ever before. They supported each other through that trying time, and Lizzie learned many things that would be of great value to her later in life.

Once she became accustomed to her grandmother’s ways, she was quite happy at Cavendish. Her uncle and aunt lived three miles away, and she enjoyed playing with their three daughters.

The pastor of the Cavendish Church invited Lizzie to join the choir. He often called upon her to sing some appropriate hymn, and in time she overcame her timidity. The pastor and his wife treated her with tender affection.

At a very young age, Lizzie worked as a missionary among the men and women who worked on her father’s farm. Many of them remembered, years afterward, the scriptures she read to them and the hymns she sang.

When Lizzie was sixteen years old, her mother’s health failed. Lizzie spent the next four years caring for her family. She devoted herself to her mother and shielded her from all anxiety.

When the young Mrs. Atherton’s health improved a little, Lizzie attended the New England Academy in Cavendish. She boarded in the village with seven other girls who were attending the school. However, her mother could only spare Lizzie for one term.

In 1837, at the age of twenty, Lizzie married Cyrus Aiken, who was nine years older than she. They honeymooned in Boston and then set out by stage and flat boat to Chicago. Their intention was to settle on the Rock River at Grand DeTour, Illinois. The area was a colony of Vermont expatriates including John Deere, the founder of the farm machinery company.

Pioneer life was tough on Lizzie and other women in the area. Tragedy struck, and she lost all four of her little boys to cholera. In 1852, her brother and sister came to comfort her in her sorrow. Only eleven days after their arrival, her sister sickened and died with cholera.

The Aiken home was struck by lightning and burned to the ground, and the family moved to Peoria. Her husband did fairly well in business, and Lizzie’s life was somewhat stable for a time.

In 1856, Cyrus became very ill, and he never recovered his mental faculties. The one who had loved and supported Lizzie was now totally dependent upon her for everything. Her father came from Vermont to comfort his daughter. He offered to take her husband to Cavendish to care for him, while Lizzie took care of matters in Peoria.

The two men arrived in Vermont on March 1, 1856. On March 16 Lizzie’s father died. To help her widowed mother and to defray the cost of her husband’s care, Lizzie worked as a domestic nurse. For the next four years, she went from house to house caring for her patients with affection and sympathy. She was finally able to pay off all of her husbands debts.

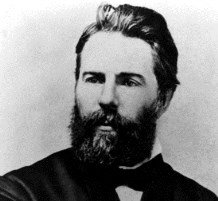

After the Civil War began, Lizzie nursed soldiers in the sick tents near Peoria, Illinois. Just outside of Springfield, Illinois, was Camp Butler, which was filled with recruits, many of whom were sick with measles. The head surgeon of the 6th Illinois Cavalry, Major Niglas of Peoria, returned home to find nurses to assist him.

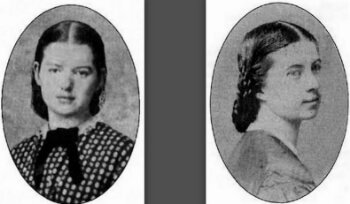

Lizzie volunteered to go with him, if he could find another woman to accompany her. An advertisement was put in the local papers, and the next morning Mary Sturgis, a widow, applied for the job and was promptly accepted. The two nurses were about the same age, and at once took a liking to each other.

In November, 1861, the 6th Illinois Cavalry was ordered to Shawneetown on the Ohio River, to go into winter quarters. Mrs. Aiken and Mrs. Sturgis went with it. As Lizzie passed from cot to cot, comforting the suffering soldiers, one of the patients asked Major Niglas: “What shall we call this kind woman?”

“You may call her Aunt Lizzie,” answered the surgeon. She was known by that name during the entire war, and her fellow nurse became known as “Mother Sturgis.”

The winter of 1861 was severe, and accommodations for the soldiers were inadequate. The number of patients ranged from twenty to eighty per day. All winter the two nurses worked in shifts, six hours on and six hours off. Lizzie worked for no pay at first, but eventually received $12.00 per month from the army.

Every afternoon Aunt Lizzie accompanied the doctor, telling him the name and the symptoms of each patient in the four wards. She also read the Bible to the soldiers, and wrote or read letters for them.

At Shawneetown in early 1862 she wrote to a friend:

Twenty-four nights in succession I have sat up until three in the morning, dealing out medicine. I cannot think of leaving these poor fellows if their is any chance of their living. Dr. Niglas tells me I have saved the lives of over 400 men. I am afraid I hardly deserve that compliment. I cannot tell you how well this work suits this restless heart of mine.

The regiment next went to Memphis, Tennessee. One day Lizzie received a note that 600 wounded soldiers had arrived at Jefferson Hospital in the city, and one of them was her brother, Bertrand. She rushed to find him, but she did not recognize him. He had been a prisoner, and had suffered greatly from starvation and exposure. Lizzie took a leave to take Bertrand home.

In February, 1864, the 6th Illinois left Memphis on a raid to Mississippi. The soldiers came to the hospital to say good bye to Aunt Lizzie. They presented her with a gold chain and an album containing all their photographs. They begged her to stay in Memphis to care for them if they should be sent back wounded, but by this time her own health was failing.

In the autumn of 1864, Aiken was given a furlough of sixty days, and a railroad ticket to Peoria. The ladies of the Peoria Loyal League gave her the money to go to Vermont and visit her mother. She rested there for three weeks.

Aiken was then called upon to go to New Hampshire to tell the loyal ladies there about her hospital work. She gladly went, because it gave her the opportunity to collect funds for her patients, and also to see her husband. He was living with relatives there, and Lizzie hoped that she would find him in improved health, but he did not recognize her. She soon returned to Memphis.

At the end of the Civil War, all of the hospitals were closed. Lizzie was sick, and Mother Sturgis helped her home to Peoria. An old friend, Mrs. Irong, cared for Lizzie as she lay ill for weeks.

Later that year, Lizzie went to Chicago to stay with a friend and recuperate. Needing to earn a living, she applied for several jobs. For a year or so she worked at a refuge for men set up by the Young Men’s Christian Association.

A newspaper editor who turned her down for a job gave her a letter of reference to the wife of a local Baptist minister. In 1867, Lizzie joined the Second Baptist Church and worked as a missionary there almost to the day of her death in January 1906, at the age of 88.

Her funeral was held in the church auditorium. The procession that passed by her coffin for over an hour demonstrated how she was loved and revered by the church and the community. There were many tributes in the local press. Her career in Chicago was almost as well known as her work during the Civil War.

Lizzie Aiken was America’s Florence Nightingale.