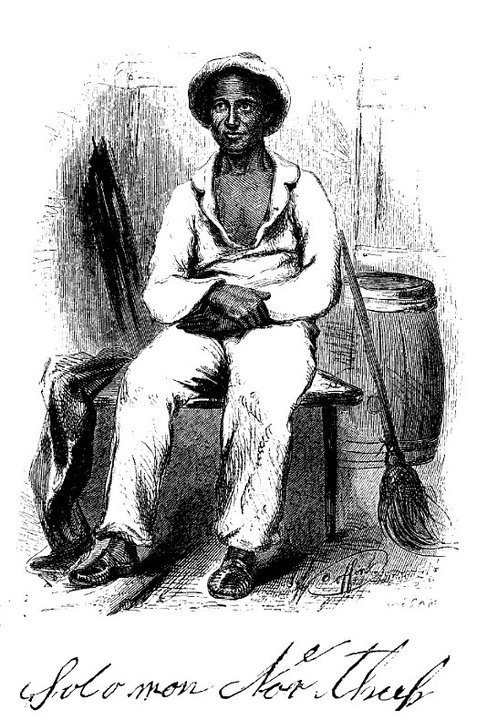

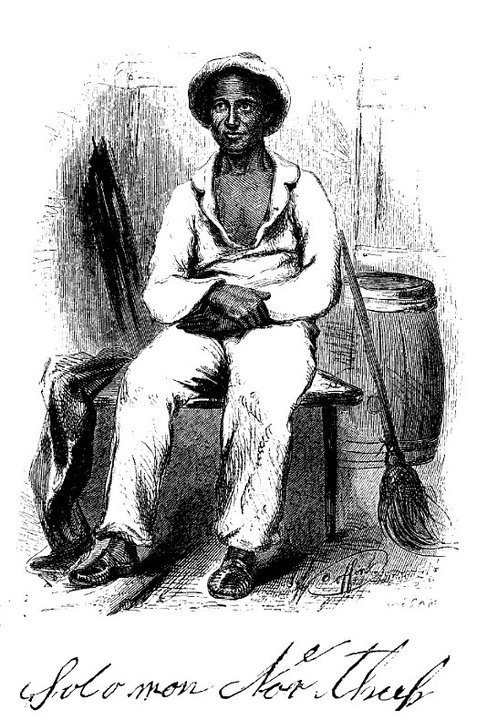

Solomon Northup was a free Black who was kidnapped and sold into slavery. I will allow him to tell parts of the story from his memoir that was published in 1853. Though the language – his or the editor’s – is stilted, it was the writing style of the times. Please excuse my cobbling together quotes that aren’t necessarily in succession, because I don’t want to interrupt the flow of the story.

Solomon was born in 1808 in Minerva, New York. His father had been a slave, but had been freed upon the death of his master. As a boy, Solomon worked on his father’s farm, and spent his free time reading and learning to play the violin.

In 1829, he married Anne Hampton. Solomon worked as a carpenter, and played the violin at dances and parties. His wife was often employed as a cook, and they made a good life together.

In the spring of 1832, they decided to take a piece of property and farm it. They started this project with one yoke of oxen, one hog, and one cow. “That year I planted twenty-five acres of corn, sowed large fields of oats, and commenced farming upon as large a scale as my utmost means would permit. Anne was diligent about the house affairs, while I toiled laboriously in the field.”

Anne “had become somewhat famous as a cook. During court weeks, and on public occasions, she was employed at high wages in the kitchen at Sherrill’s Coffee House. We always returned home with money in our pockets; so that, with fiddling, cooking and farming, we soon found ourselves in the possession of abundance.”

In March 1834, they moved to Saratoga Springs, where Solomon drove a hack for two years.

After this time, I was generally employed through the visiting season, as also was Anne, in the United States Hotel. In winter seasons, I relied on my violin.

I continued to reside at Saratoga until the spring of 1841. The flattering anticipations which, seven years before, had seduced us from the quiet farm house on the east side of the Hudson, had not been realized. Though always in comfortable circumstances, we had not prospered.

At this time we were the parents of three children – Elizabeth, Margaret, and Alonzo. They filled our house with gladness. Their young voices were music in our ears. Their presence was my delight, and I clasped them to my bosom with as warm and tender love as if their clouded skins had been as white as snow.

Solomon’s story touched my heart, but I can’t believe a father would refer to his children in this way, as having “clouded skins,” and that he loved them as if they were white. This disturbs me, but again, maybe it is a sign of the times. Was poor Solomon so brainwashed that he actually formed these thoughts of his own accord?

Or did the editor write those words? The editor’s name was David Wilson. I couldn’t discover any information about this man, but in the Editor’s Preface of the book about Solomon’s life, Twelve Years a Slave, the editor states:

Unbiased, as he conceives, by any prepossessions or prejudices, the only object of the editor has been to give a faithful history of Solomon Northup’s life, as he received it from his lips. In the accomplishment of that object, he trusts he has succeeded, notwithstanding the numerous faults of style and of expression it may be found to contain.

Now isn’t that a mouthful?

The last paragraph of the first chapter of the book says: “Thus far the history of my life presents nothing whatever unusual – nothing but the common hopes, and loves, and labors of an obscure colored man, making his humble progress in the world.”

In March 1841, Solomon was

walking about the village of Saratoga Springs, thinking to myself where I might obtain some present employment, until the busy season should arrive. Anne, as was her usual custom, had gone over to Sandy Hill, a distance of some twenty miles, to take charge of the culinary department at Sherrill’s Coffee House, during the session of the court. Elizabeth [his daughter], I think, had accompanied her. Margaret and Alonzo [their other two children] were with their aunt in Saratoga.

Solomon met two white men, Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, who claimed they worked for a traveling circus and were on their way to rejoin it in Washington, DC. As they traveled, they were staging exhibitions to draw crowds to the circus.

When they learned that Solomon played the violin,

they remarked that they had found much difficulty in procuring music for their entertainments, and that if I would accompany them as far as New York, they would give me one dollar for each day’s services, and three dollars in addition for every night I played at their performances, besides sufficient to pay the expenses of my return from New York to Saratoga.

Needing the money for his family, Solomon accepted immediately. Believing he would only be gone a day or two, he did not tell his family that he was leaving.

When they reached New York,

I supposed my journey was at an end and expected in a day or two at least, to return to my friends and family at Saratoga. Brown and Hamilton, however, began to importune me to continue with them to Washington. They alleged that immediately on their arrival, now that the summer season was approaching, the circus would set out for the north. They promised me a situation and high wages if I would accompany them… I finally concluded to accept the offer.

Though Solomon was a free black man in New York state, slavery was still legal in the District of Columbia. Free blacks traveling through slave states had to carry papers to prove that they were free or face the possibility of being accused of being a runaway slave. His companions convinced Solomon to go to the court and get papers certifying his free status. They arrived in Washington just after President William Henry Harrison died. Brown and Hamilton wanted to pay their respects by attending the funeral procession the following day, so Solomon went along. The three men spent the rest of the afternoon in a saloon.

They would pour out a glass and hand it to me. Toward evening, I began to experience most unpleasant sensations. I felt extremely ill. Brown and Hamilton advised me to retire. In a short time I became thirsty. My lips were parched. I found the way at last to a kitchen in the basement, where I drank two glasses of water… but by the time I reached my room again, the same burning desire of drink had returned.

In the course of an hour or more, I was conscious of someone entering my room. Whether Brown and Hamilton were among them, is a mere matter of conjecture. I only remember that I was told that it was necessary to go to a physician and procure medicine. From that moment I was insensible.

When Solomon finally awoke, he found himself alone in the darkness.

I was hand cuffed. Around my ankles also were a pair of heavy fetters. One end of a chain was fastened to a large ring in the floor. Where was I? Where were Brown and Hamilton? I had not only been robbed of liberty, but my money and free papers were also gone! Then did the idea begin to break upon my mind that I had been kidnapped. But that I thought was incredible.

Outside the cell where Solomon was being held was

a small passage that led up a flight of steps into a yard, surrounded by a brick wall ten or twelve feet high. It was like a farmer’s barnyard in most respects, save it was so constructed that the outside world could never see the human cattle that were herded there.

The building to which the yard was attached, was two stories high, fronting on one of the public streets of Washington. Its outside presented only the appearance of a quiet private residence. Within plain sight of this same house, looking down from its commanding height upon it, was the Capitol.

Solomon soon learned that he was being held in a slave pen owned by a man named James Burch, who informed Solomon that he was to assume the identity of a runaway slave from Georgia. When Solomon insisted again and again that he was free, Burch ordered the paddle and cat-o-nine-tails to be brought in. The paddle was a piece of hardwood board, 18″ or 19″ long. The cat was a large rope of many strands—the strands unraveled, and a knot tied at the extremity of each.

Solomon was

roughly divested of my clothing. My feet were still fastened to the floor. Drawing me over a bench, face downwards, Burch’s assistant placed his heavy foot upon the fetters between my wrists, holding them painfully to the floor. With the paddle, Burch commenced beating me.

He stopped and asked if I still insisted I was a free man. I did insist upon it, and then the blows were renewed. When he was tired, he would stop and repeat the same question, and receiving the same answer, continue his cruel labor. Still I would not yield. All his brutal blows could not force from my lips the foul lie that I was a slave. At length, the paddle broke. He seized the rope. This was far more painful than the other.

At last I became silent to his repeated questions. I would make no reply. At length, his assistant said that it was useless to whip me anymore—that I would be sore enough. Thereupon Burch desisted, saying that if I ever dared to utter again that I was entitled to my freedom, the castigation I had just received was nothing in comparison with what would follow. I was left in the darkness as before.

Solomon was then shipped south by steamer to New Orleans, to another slave pen operated by Burch’s partner, Theophilius Freeman. Solomon was sold for $1000 to a devout Baptist by the name of William Ford, who brought Solomon to the Marksville area of Louisiana.

Ford was kind to his slaves. Solomon worked hard as a carpenter out of the respect for his owner, but he was too afraid to reveal his true identity to Ford. In the winter of 1842, Solomon was sold to John Tibeats, who was an evil master. Solomon fought against Tibeats while he was trying to whip him: a slave crime that was punishable by death. Ford interceded and forced Tibeats to sell Solomon to another owner.

Eventually Solomon became the property of Edwin Epps, who owned a cotton plantation, where slaves worked over 360 days a year and could be whipped for stopping to rest.

In the latter part of August begins the cotton picking season. Each slave is presented with a sack. A strap is fastened to it, which goes over the neck, holding the mouth of the sack breast high, while the bottom nearly reaches the ground. Each one is also presented with a large basket that will hold about two barrels. This is to put the cotton in when the sack is filled.

The slave picks down one side of a row and back upon the other, gathering all that has blossomed, leaving the unopened bolls for a succeeding picking. When the sack is filled, it is emptied into the basket and trodden down. An ordinary day’s work is two hundred pounds. A slave who is accustomed to picking is punished if he or she brings in a less quantity than that.

The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as it is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they often times labor till the middle of the night.

In 1845, the caterpillars almost totally destroyed the cotton crop throughout that region. There was little to be done, so the slaves were necessarily idle half the time. There came a rumor that wages were high, and laborers in great demand on the sugar plantations in St. Mary’s parish.

The planters, on the receipt of this intelligence, made up a drove of slaves to be sent down to St. Mary’s to work in the cane fields. In the month of September, there were one hundred and forty-seven collected, myself among the number. Of these about one-half were women.

It is the custom in Louisiana, as I presume it is in other slave States, to allow the slave to retain whatever compensation he may obtain for services performed on Sundays. In this way, only, are they able to provide themselves with any luxury or convenience whatever. I remained in St. Mary’s until the first of January, during which time my Sunday money amounted to ten dollars.

I met with other good fortune, for which I was indebted to my violin, my constant companion. There was a grand party of whites assembled, and I was employed to play for them, and so well pleased were the merry-makers with my performance, that a contribution was taken for my benefit, which amounted to seventeen dollars. With this sum in possession, I was looked upon by my fellows as a millionaire.

During these travels in sugar cane country, Solomon “was bold enough one day to present myself before the captain of a steamer, and beg permission to hide myself among the freight,” after he had overheard that the captain was “a native of the North. I did not relate to him the particulars of my history, but only expressed an ardent desire to escape from slavery to a free State. He pitied me, but said it would be impossible.”

Finally, early in 1852, his eleventh year of slavery, Solomon had a stroke of luck. Master Epps hired a carpenter to build him a new mansion. The carpenter’s name was Bass, and at that time he lived in Marksville, a nearby town. He was originally from Canada, and was not hesitant in stating his hatred for slavery.

Solomon’s memoir states:

He [Bass] was a large man, between forty and fifty years old, of light complexion and light hair. He was a bachelor, having no kindred living, as he knew of, in the world. He had lived in Marksville three or four years, and in the prosecution of his business as a carpenter, was quite extensively known. He was liberal to a fault; and his many acts of kindness and transparent goodness of heart rendered him popular in the community.

The more I [Solomon] saw of him, the more I became convinced he was a man in whom I could confide. Nevertheless, my previous ill-fortune had taught me to be extremely cautious. It was not my place to speak to a white man except when spoken to.

In the early part of August he [Bass] and myself were at work alone in the house, the other carpenters having left, and Epps being absent in the field. Now was the time, if ever, to broach the subject and I resolved to do it, and submit to whatever consequences might ensue.

He [Bass] assured me earnestly he would keep every word I might speak to him a profound secret. It was a long story, I told him, but if he would see me that night after all were asleep, I would repeat it to him. About midnight, when all was still and quiet, I crept cautiously from my cabin, and silently entering the unfinished building, found him awaiting me.

Having told him my story I besought him to write to some of my friends at the North, acquainting them with my situation, and begging them to forward free papers, or take such steps as they might consider proper to secure my release. He promised to do so, but dwelt upon the danger of such an act in case of detection, and now impressed upon me the great necessity of strict silence and secrecy.

When Bass next went to Marksville, he wrote letters to the people whose names Solomon had provided. One he directed to the Collector of Customs at New York, thinking that there must be a record of the free papers that Solomon had obtained while on the trip with Brown and Hamilton.

After this time we seldom spoke to, or recognized each other. The remotest suspicion that there was any secret understanding between us – never once entered the mind of Epps, or any other person, white or black, on the plantation.

At the end of four weeks, he (Bass) was again at Marksville, but no answer had arrived. I was sorely disappointed, but still reconciled myself with the reflection that sufficient length of time had not yet elapsed. Six, seven, eight, and ten weeks passed by, however, and nothing came.

Finally my master’s house was finished, and the time came when Bass must leave me. The night before his departure I was wholly given up to despair. I had clung to him as a drowning man clings to the floating spar. The generous heart of my friend and benefactor was touched with pity at the sight of my distress. He endeavored to cheer me up, promising to return the day before Christmas. He exhorted me to keep up my spirits.

Faithful to his word, the day before Christmas, just at night-fall, Bass came riding into the yard.

“How are you,” said Epps, shaking him by the hand, “glad to see you.”

“Quite well, quite well,” answered Bass.

They passed into the house together; not, however, until Bass had looked at me significantly.

It wasn’t until early the next morning that Bass entered Solomon’s cabin to inform him that no letter had come.

“Oh, do write again, Master Bass,” I cried.

“No use,” Bass replied. I fear the Marksville post-master will mistrust something, I have inquired so often at his office. Too uncertain—too dangerous.”

“Then it is all over,” I exclaimed. “Oh, my God, how can I end my days here!”

“You’re not going to end them here,” Bass said. “I have a job or two on hand which can be completed by March or April. By that time I shall have a considerable sum of money, and then, I am going to Saratoga myself.”

Solomon was overjoyed and thankful to his friend for undertaking such a journey on his behalf. But, as it turned out, it would not be necessary.

Monday morning, the third of January, 1853, we were in the field. It was a raw, cold morning, such as is unusual in that region. Our conversation was interrupted by a carriage passing rapidly towards the house. Looking up, we saw two men approaching us through the cotton-field.

Bass’s letters had reached New York the previous September. One of the letters was forwarded to Solomon’s wife, Anne, who had asked the advice of a lawyer by the name of Henry Northup, who was a member of the family that once owned Solomon’s father. Henry discovered that a New York State Law passed in 1840 declared that if a free black resident was unlawfully enslaved they could be recovered.

Upon hearing this, the Governor of New York had appointed Henry Northup to go to Louisiana and bring Solomon home. The two men who approached Solomon in the cotton field that morning were Henry Northup and the local sheriff, in case Epps should try to prevent them from taking Solomon. He did, but it did him no good. Solomon was soon on his way home to his family and freedom.

Solomon’s history past that point is sketchy. It was reported that he became involved in the abolitionist movement and lectured on slavery in the northeastern United States. No known records about him exist after 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, and nothing is known about his death.

Researchers report that he disappeared in 1863 while in Boston giving lectures. Some say he may have been kidnapped or killed by persons unknown. Others feel that the sudden disappearance of such a well-known person would have been noticed. Maybe he died of natural causes, but he was only 55 years old.

His memoir, Twelve Years a Slave, published in 1853, simply states:

My narrative is at an end. I have no comments to make about the subject of slavery. Those who read this book may form their own opinions. If I have failed in anything, it has been in presenting to the reader too prominently the bright side of the picture. I hope henceforward to lead an upright though lowly life, and rest at last in the church yard where my father sleeps.

I’m sure there will be comments about my writing a post about a man, and I apologize for the lengthy article, but Solomon’s story touched my heart. And there is a very strong woman at the core of this tale, his wife Anne, who worked hard, raised their children, and carried on with life as best she could in Solomon’s absence—for many of those years not knowing what had happened to him.