Hello, my name is Charleston, and I live in the beautiful state of South Carolina, one of the thirteen original colonies in America, and I want to tell you my story. Some of it is not pleasant, but it is my history, and I must tell it true. I’m a rather large woman, but I like to think I’m well-proportioned.

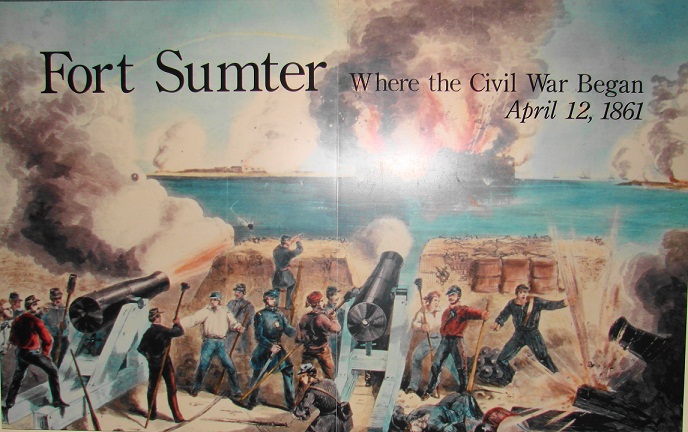

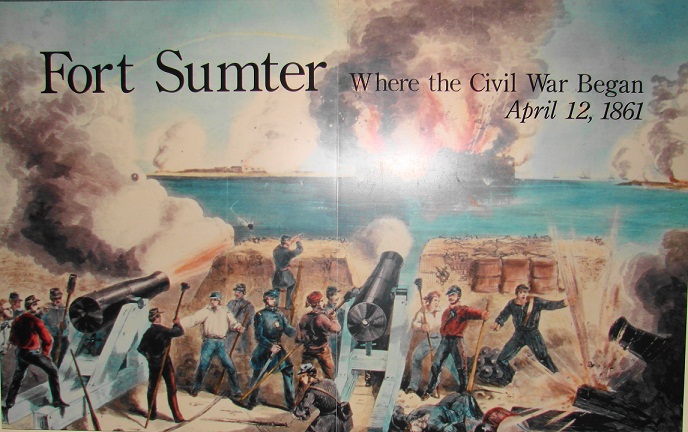

The Bombardment of Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter burning in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861

My history is long and complicated, so I will try to hit the high spots. And I will break it down into time periods, so as not to give you a great big dose at one time. My language may be a little “home-fried” at times, but I will make sure you get my meaning.

For thousands of years before the Europeans arrived, my state was occupied by Native American tribes, the largest of which were the Cherokee and the Catawba. Their population greatly declined after the Europeans arrived. They had no immunity to European diseases, such as smallpox. Epidemics killed thousands of them, reducing some tribes by as much as two-thirds of their population.

I was born way back in 1670. Geez, I’m getting old! I was originally named Charles Town, in honor of King Charles II of England. I became the capital of the Carolina colony. African Slaves brought their knowledge of rice planting with them to my shores, and they were accustomed to our hot weather. Their genes made them prone to sickle cell anemia, but also made them resistant to malaria and yellow fever.

By 1690, I was America’s fifth largest city, home to mostly English settlers, and one of the wealthiest cities in the country. I was prone to attacks from pirates, Native Americans, and the Spanish and the French, who were still trying to lay claim to my territory. My colonists erected a wall around my small settlement to aid in my defense.

In 1710, my colony was divided into South Carolina and North Carolina. The settlers built plantations throughout the coastal lowcountry and grew profitable crops of rice and indigo. African slaves were brought into the area in large numbers to provide labor for the plantations, and by 1720 they formed the majority of my population.

After the British finally retreated in December 1782, my name was officially changed to Charleston. In the ensuing years, I grew and prospered. With the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, cotton became a major crop. The cotton plantations relied heavily on slave labor. Dissatisfaction with the tariff policies of the our government also grew during that time.

Slaves were also my main labor force in the city, working as domestics, artisans and laborers. Many black Charlestonians spoke Gullah, which was based on African, French, German, English and Dutch dialects. In 1807, the Charleston Market was founded. It soon became the center of the black community, with many slaves and free people of color staffing the stalls.

By 1820, my population had grown to 23,000, over 50% of whom were black. Many of my free blacks had become artisans and entrepreneurs, amassing more wealth than many of my whites. My blacks established their own social hierarchy.

Most of my free blacks had been given their freedom in the last will and testament of their masters, who commonly manumitted their mulatto children and their mistresses. They were known in the city as free people of color and were admired for their light skin. They formed the Brown Fellowship Society, which excluded blacks, slaves, and the poor.

The Free Dark Men of Color Society was formed to give its members a social outlet, allowing them to celebrate their darkness, and to define themselves as separate from both mulattoes and slaves, which was still the largest social group in my city.

Discrimination amongst discrimination!

In 1822, a plan for a slave revolt designed by Denmark Vesey, a free black, was discovered. This incident frightened my white community, and the activities of free blacks and slaves were severely restricted. Hundreds of free blacks, slaves, and white supporters were accused of being involved in planning the uprising.

In 1800, Vesey had won a $1,500 lottery prize, with which he bought his freedom and opened a carpentry shop. Soon this highly skilled artisan was respected by blacks and whites. He prospered, but he was not content with his life.

Vesey hated slavery, and spoke out against the abuse and exploitation of his people. He believed in equality for all and vowed never to rest until his people were free. He recruited a group of helpmates to help liberate the slaves in my city and on neighboring plantations, which included his own children.

On May 30, 1822, a slave named George Wilson told his master about the revolt, which was set to take place on July 14th. Once the plot was betrayed, officials quickly arrested the leaders. After a lengthy trial, Vesey and 36 others were hanged for plotting to overthrow slavery. But Vesey was still remembered during the Civil War, when his name was invoked in the battle cry of black Union soldiers.

(Research has shown that the uprising was all a fabrication created by then-mayor, James Hamilton, to use as “a political wedge issue” against then-governor Thomas Bennett, who owned four of the slaves who were accused of being involved in the conspiracy. As proof, historians have cited a letter written by the governor to Thomas Jefferson, in which he stated that the conspiracy was only the result of the hysteria of white Charlestonians, who were terrified that their slaves would rise up and kill them in their sleep. Does that not that suggest to you that they knew that slavery was a sin against alll mankind?)

Next, I will take up my narrative with my antebellum period, when the pot really began to boil. Oh, they were hard times.

Now, I want to tell you of two of my citizens, Angelina and Sarah Grimke. They grew up in one of my prominent families. Their father was a judge, and he also ran a profitable cotton plantation, Beaufort, with many slaves. Sarah had abhorred slavery since childhood, but her convictions were soon to be strengthened.

In 1819, she went to Philadelphia with her father, and was introduced to the Quakers. The Quakers condemned slavery, which immediately won Sarah’s heart. She also admired them because they allowed women to become leaders in their churches. Sarah came back home, but she could no longer turn a blind eye to the suffering of the slaves. She moved to the North. Her sister Angelina soon joined her there.

The Grimke sisters were good people! I was so sorry to see them go, but I understood their need to move away from the horrors of slavery. Though I was a growing city, there were many things I couldn’t change. People will do as they will do. The Grimkes would work tirelessly for the rest of their lives, trying to make this old world a better place to live in.

But, I digress, as I am wont to do. Somewhere along in there, a controversy began over the degree in which the Federal government should be allowed to mess in South Carolina’s affairs. During this period, over 90 percent of Federal funding was generated from import duties, and we paid heavily. As time went by, my people became more and more devoted to the idea that state’s rights were superior to the Federal government’s authority.

In the 1820s, South Carolinian John C. Calhoun developed the theory of nullification, which allowed a state to reject any federal law it considered to be a violation of its rights. In 1832, South Carolina passed the ordinance of nullification, which was pointed directly at the most recent tariff acts.

Federal soldiers came to our forts and began to collect tariffs by force! A compromise was reached, and the tariffs were gradually reduced, but hard feelings were created, and continued to grow in the coming decades.

During the antebellum period, Charleston continued to serve as a center of commercial activity for the South’s plantation economy, which depended heavily upon slave labor. Slaves were regularly sold on the north side of the Customs House.

My white folk remained uneasy about their slaves. In 1834, the legislature decreed that blacks could no longer teach each other, but that didn’t stop them. Blacks still schooled their children. They just became more secretive about it.

In 1841, the “Act to Prevent the Emancipation of Slaves” was passed. The purpose of this law was to root out slaves who were owned by family members or white guardians, and lived as free, and to prevent them from inheriting property.

Then, in 1846, the legislature passed a badge law. Black citizens were required to wear a metal badge, which told if they were free, slave, or indifferent. This law was intended to prohibit slaves from passing as free blacks. But all these attempts by whites to better define the lines between slave and free had no lasting effect.

From 1810 to 1850, I was an African city. Slaves made up around 50 percent of my population, while free blacks comprised between 5 and 8 percent during those forty years. Blacks filled the labor shortage left by whites, claiming a prominent role in Charleston’s economy.

But between 1850 and 1860, even though the free black population remained stable, the total black population in the city fell to only 42 percent. Blacks were losing their strong position in the labor force, while white laborers gained, economically and socially.

In 1856, a city ordinance outlawed the practice of public slave sales. Several sales rooms and marts popped up. The Slave Mart was constructed in 1859. When sales were held, the slaves stood on auction tables, so perspective buyers could see them up close during the auction. The building was used for this purpose until the defeat of the South in the Civil War led to the end of slavery.

By 1858, racial tensions were rampant, brought on by hostile white laborers, who disliked having to compete with blacks for jobs. Tensions surrounding the place of slaves and free blacks in society rose, especially slaves who “worked out” (worked for people other than their masters and were allowed to keep some of their earnings). What had taken decades for blacks to build, hostile whites obliterated in just a few years.

And the symbols of wealth and education black elites used to distinguish themselves from slaves and poor blacks were the same as those used by white aristocrats to separate themselves from white laborers. This could be interpreted as attempts by the black elites to portray themselves as better than white laborers, with whom they lived in close proximity. And that would never do!

In 1858, my white workers pressured authorities to reinstate the 1822 law that prohibited slaves from hiring themselves out. White laborers also wanted to abolish the rights of free blacks and push them toward slavery, but white aristocrats came to the aid of free blacks, insisting that they occupied a valuable place in the local economy.

In 1859, my white elites again came to the aid of free blacks. A bill that proposed to enslave all blacks appeared before the state legislature. How shocking! Using the same defense as they had the year before, the white political aristocracy stopped the bill dead in its tracks.

In 1860, after more pressure from white laborers, police began strictly enforcing the slave badge law. Only the mulatto elite were able to avoid legal harassment. By mid-1860, the police were enforcing all of the old restrictive laws. They were arresting free blacks who had been illegally manumitted after 1820 and free blacks without guardians.

Many poor free blacks, who could not prove their right to freedom, ran to their old masters to be re-enslaved and bought slave badges, rather than being sold on the auction block to God knows where. Oh, how my people suffered!

I have had a colorful history – yes, color has played a major role in my history. All my people – white, dark and mulatto – were so dear to me, but coexistence had always been a problem. They clamored for my approval, but I did not like to take sides.

On the eve of the Civil War, my society was changing drastically. The rights of all blacks in my city were being threatened, even the mulatto elite who had managed to stay out of the fray until then. Mulattos, as a rule, were sophisticated and educated, and they needed the white aristocracy and the slaves to secure their position in society.

Unhappy over free trade restrictions and calls for the abolition of slavery, South Carolina seceded from the union on December 20, 1860. By the time the constitutional convention to establish the Confederate government convened in February 1861, six other states had joined her.

After her secession, South Carolina could no more allow a Union garrison to remain at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, than President Abraham Lincoln could withdraw those forces, which in his view would be recognizing South Carolina as a sovereign state.

Shortly after his inauguration, President Lincoln learned that the soldiers at Fort Sumter were running out of food. On April 6, 1861, he informed South Carolina Governor Pickens that he planned “to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only.” But the Confederate cabinet decided to fire upon Fort Sumter before their supplies arrived.

In my estimation, only Secretary of State Robert Toombs was clear-headed enough to see the calamity that action would cause. He told Jefferson Davis that an unwarranted attack “will lose us every friend at the North. It is unnecessary. It puts us in the wrong.” More prophetic words never passed his lips.

At any rate, Confederate forces opened fire on the Union garrison at Fort Sumter, and they returned fire. An artillery duel lasted all day April 12 and into the following day, and the fort was gradually being destroyed. A fire broke out, which could have exploded the gunpowder stored in the fort’s magazine. At noon on April 13, the Union forces raised a flag of surrender, and they abandoned the fort the following day.

The next day, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to help put down the rebellion. Without that action, maybe we could have negotiated a solution to our many differences, but I hesitate to place blame. So many were so wrong about so many things, especially those who thought we could peacefully leave the Union without recrimination.

I guess we were so worked up over protecting the rights of our states, we were blind to the dangers ahead. If we had foreseen the four years of bloody conflict that would follow, we might have reconsidered our position. Hard to say.

Amidst all the comings and goings of war, our next major calamity occurred in the spring of 1862, called the Battle of Secessionville. My harbor was in the grips of the Federal blockade, and Union forces landed on James Island, planning to attack Charleston.

On the morning of June 15, 1862, Federal troops made an early morning surprise attack on a fort at Secessionville. Advancing in the darkness, their progress was hindered by hedgerows and knee-deep weeds in an old cotton field. Confederate pickets were alerted at 5 a.m. A few Yankees managed to clamber up the face of the fort, but soon encountered strong resistance from the Rebels. A withdrawal was ordered. The battle was over by 9 a.m.

On June 21, 1862, the Yankees made an amphibious attack to cut the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. The assault was unsuccessful, one of many such assaults along my coastline and the many islands along my shore.

Throughout the summer of 1863, the Federals attacked Fort Wagner on Morris Island. They were successful in mounting some batteries there. On August 17th, they opened fire on Fort Sumter and my defenses, which continued for a week. The garrison at the fort were severely pounded, but held their own. The siege of Fort Wagner continued.

Operations against the defenses of my city never abated. A nighttime attack during the first week in September forced the evacuation of Fort Wagner. The Yankees then occupied Morris Island. They attempted a surprise attack on Fort Sumter, but were repulsed.

The battle for control of Fort Sumter continued until the end of the war, subjecting my streets and homes to almost constant artillery fire. My citizens tried to save my historic buildings from the 1700s. The constant bombardment of my city’s defenses caused massive damage.

My wonderful city was a war zone, with hollowed-out buildings, destroyed residences, and shattered dreams. My cobblestone streets were bordered by free-standing pillars that once held up verandas, and the remains of brick chimneys jutted up into the sky like bony fingers, but the war had accomplished what Denmark Vesey could not, the abolition of slavery.

My former slaves – what hard times they had. They didn’t know where they belonged, so dependent had they been on their former masters for food, clothing, and shelter. They didn’t know how to care for themselves. Many stayed where they were, not knowing what else to do. There were no jobs. Their masters most likely had lost their plantations. If they managed to hang onto their land, they had no money to pay the former slaves for their labor.

And my poor sisters, the women who survived the Civil War, how they suffered. So many had lost all their menfolk, had children to raise, many of their homes destroyed by war. And what a time to have to start over, with nothing. To try to salvage their land, to plant crops, to beg others for help. Once proud women were reduced to the basest level, along with everybody else. It would take generations, if ever, to restore their lives to what little comfort they could find.

My tale is at an end. I hope you have enjoyed my history as much as I have delighted in telling it to you. Some of it was not pleasant, but it has made me what I am today – a beautiful place that welcomes people of all colors.