Union Spy in the Confederate Capital

Elizabeth Van Lew, a well-to-do resident of Richmond, Virginia, recruited and operated an extensive network of spies who gathered intelligence for the Union in the shadow of the Confederate White House. Van Lew was also an Angel of Mercy for the Union soldiers who were being held at Libby Prison near her home. Her gifts of food and clothing meant the difference between life and death for many inmates there.

Elizabeth Van Lew, a well-to-do resident of Richmond, Virginia, recruited and operated an extensive network of spies who gathered intelligence for the Union in the shadow of the Confederate White House. Van Lew was also an Angel of Mercy for the Union soldiers who were being held at Libby Prison near her home. Her gifts of food and clothing meant the difference between life and death for many inmates there.

Early Years

Elizabeth Van Lew was born October 25, 1818 in Richmond, Virginia, the eldest daughter of Eliza Baker Van Lew and John Van Lew, a prominent Virginia businessman who owned a prosperous hardware business and several slaves. Elizabeth attended a Quaker school in Philadelphia, and she came home an outspoken abolitionist. She was heartbroken over the suffering caused by the institution of slavery.

Family Slaves

After John Van Lew’s death in 1843, the family freed their nine slaves, but some remained with the Van Lews as paid servants, including Mary Elizabeth Bowser. A major recession followed the financial crisis in the United States called the Panic of 1837 and lasted until the mid-1840s while prices and unemployment increased and wages decreased. During that time Elizabeth Van Lew used the $10,000 she had inherited from her father to purchase and then free relatives of their former slaves so they would not be sold away from their families to the Deep South. Elizabeth’s brother was a regular visitor to Richmond’s slave market in those years.

Elizabeth Van Lew never married. She was petite with a pointed chin and a long thin nose. She wore her hair pinned up in the back, with ringlets falling around her face, accenting her brilliant blue eyes. Not the kind of lady one would suspect of operating an extensive spy ring for the Union during the Civil War, which is probably why she was so successful.

Aiding Libby Prisoners

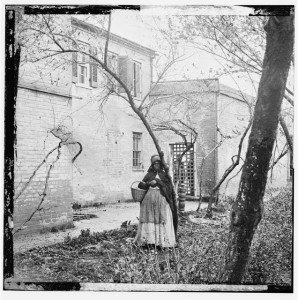

Van Lew lived with her widowed mother in an elegant three-story mansion on Church Hill, the highest of Richmond’s seven hills. Van Lew took great pride in her Richmond roots, but she fervently opposed slavery and secession, writing her thoughts in a secret diary she kept buried in her backyard. Her home was reputed to be the meeting place for other Richmond Unionists, as well as a hiding place for escaped prisoners.

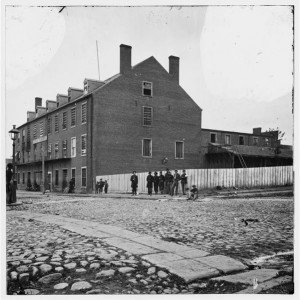

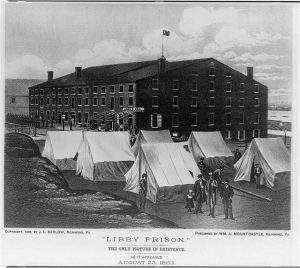

From her garden, Van Lew could see the old ship chandler’s warehouse six blocks away – a huge rectangular building with four floors – which the Confederates converted into what they called Libby Prison. After the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, she began hearing of the suffering of the hundreds of Union officers who were housed there, often in desperate conditions. She quickly approached Prison Commandant Lieutenant David Todd (half-brother of Mary Todd Lincoln [link]) and requested a nursing position within the prison. She was denied, but she managed to get permission to bring baskets of food, medicines and books to them. Though her fellow Richmonders scowled at her, they did not interfere.

This excerpt from the Richmond Examiner on July 29, 1861 shows that Elizabeth Van Lew wasted no time in aiding the inmates at Libby Prison:

SOUTHERN WOMEN WITH NORTHERN SYMPATHIES – Two ladies, mother and daughter, living on Church Hill, have lately attracted public notice by their assiduous attentions to the Yankee prisoners confined in this city. Whilst every true woman in this community has been busy making articles of comfort or necessity for our troops, or administering to the wants of the many hundreds of sick, who, far from their homes, which they left to defend our soil, are fit subjects for our sympathy, these two women have been expending their opulent means in aiding and giving comfort to the miscreants who have invaded our sacred soil, bent on rapine and murder, the desolation of our homes and sacred places, and the ruin and dishonour of our families.

Out upon all pretexts of humanity! The largest human charity can find ample scope in kindness and attention to our own poor fellows who have been stricken down while battling for our country and our rights. The Yankee wounded have been put under charge of competent surgeons and provided with good nurses. This is more than they deserve and have any right to expect, and the course of these two females, in providing them with delicacies, buying them books, stationery and papers, cannot but be regarded as an evidence of sympathy amounting to an endorsation of the cause and conduct of these Northern Vandals.

Van Lew also gathered information about Confederate troop movements from the new inmates, who passed messages to her by faintly underlining certain words and scribbling hen scratches in the margins of the books they borrowed from her. She then relayed information about Confederate operations to Union generals and assisted in the care and sometimes escape of Union prisoners of war. By September 1861, Elizabeth Van Lew was providing funds to be used to bribe Confederate prison guards, who would then allow Union prisoners escape from Libby Prison. She continued these activities throughout the war.

Richmond, Virginia

Espionage for the Union

When Virginia seceded in the spring of 1861, Van Lew did not desert the Union in favor of the Confederacy. In her opinion, she was a loyal Virginian, and the secessionists were traitors. She supported the Union throughout the Civil War. Ms. Van Lew was 43 years old when she began spying for the Union, and she quickly assembled a circle of a dozen or so accomplices: slaves and farmers, seamstresses and storekeepers, black and white, working in plain sight for the North.

Spying at the Confederate White House

Van Lew secured a position for Bowser as a servant at the Confederate White House in Richmond. Confederate President Jefferson Davis probably assumed that she was an illiterate slave; Davis left important documents in plain view on the desk in his study. However, Bowser had attended a Quaker school in Philadelphia, and she had a photographic memory, and she gathered critical information about the Confederacy.

Bowser and Van Lew would meet after dark near the Van Lew farm to exchange information. Hiding her curls under a huge bonnet, Van Lew passed herself off as a poor countrywoman riding about in her buggy. Van Lew used her former slaves as couriers; they carried secret messages in the soles of their shoes and baskets of eggs and produce they sold on the streets of Richmond.

In this excerpt from an article in the Richmond Daily Dispatch of July 17, 1883, entitled ‘The Richmond Spy’ many of Miss Van Lew’s secrets were revealed:

Miss Van Lew got young Ross, a nephew of Franklin Stearns, the rich Unionist of Richmond, appointed to an office in Libby Prison. Ross helped a great many of our officers to escape from that horrible place, and so well did he play his part that not only was he not suspected by the Confederates, but the most of our boys in the prison who did not escape considered him one of the most brutal of their jailers, and when the end came would have been very glad to put an end to him.

Several years ago I met Captain Lounsbery, who had been confined in Libby, and he asked me about Ross, who died several years ago. … Lounsbery said that one afternoon Ross came into the prison as usual to call the roll, cursing the d- Yankees, and as he passed him said in a low tone, “Be in my office at 9:30 to-night.” Lounsbery did not know what to make of this, but he determined to find out what it meant. To his surprise he had no difficulty in getting to the office past several guards.

Once there he found Ross, who gruffily said: “See here, I have concluded to try you and see if you can do cooking. Go in there and look around. See what you can find, and I will see to your case after awhile.” Lounsbery went into a back room, where he found a complete Confederate uniform hanging over a chair. He took in the situation instantly, and donned the uniform as speedily as possible and walked back into the office, which he found vacant, and stepped out into the street. The guard did not stop him, and he had walked only a few steps from the door when a black man accosted him and asked if he desired to find the way to Miss Van Lew’s house. He replied that he did, and was guided to her residence, on Church Hill, where he was secreted until an opportunity was found to get him out of Richmond. He got off safely and came into our lines. …

She had a farm in the country on the other side of the James river from us and below Richmond. Every day two of her trusty Negro servants drove into Richmond with something to sell – milk, ckickens, garden-truck, etc. The Negroes wore great, strong brogans, with soles of immense thickness, made by a Richmond shoemaker, whose name I will not give because he is still living and doing business in that city. Shoes were pretty scarce in the Confederacy in those days, but Miss Van Lew’s servants had two pairs each and changed them every day. They never wore out of Richmond in the afternoon the same shoes they wore into the city in the morning. The soles of these shoes were double and hollow, and in them were carried through the lines letters, maps, plans, etc., which were regularly delivered to General Grant, at City Point, the next morning. The communication was kept up at our end – by means of a steam-launch, which used to land a scout … on the opposite side of the James early in the night. Before daylight he would communicate with Miss Van Lew’s messenger and return to our side of the river.

When we got the news that the Confederates were evacuating Richmond, General Grant, who was at the front, before Petersburg, sent back a dispatch to Colonel Ely S. Parker, of his staff, to go into the city at once and see that order was preserved and that all of Miss Van Lew’s wants were supplied. I accompanied him, and went immediately to Miss Van Lew’s house to carry out General Grant’s orders. The house was filled with many Union people. Among them was young Ross, who said he wanted to keep out of sight, as some of our men who had been prisoners in Libby had declared they would kill him on sight. …

A day or two before the surrender a mob went to her place determined to destroy her house. She appeared and soon recognized some of the men in the crowd. She addressed them, admitting that she had been in communication with ‘Mr. Grant.’ “I can tell you, too,” said she, “that Mr. Grant will be in this city within twenty-four hours, and if you harm me or burn a single stick of my property you will suffer. Your house, Mr. Dabney – yours, Mr. Johnson, will have to go.” And so she went on calling the names of individuals and defying them until the mob finally dispersed without carrying out any of their threats.

In 1865, when General Ulysses S. Grant was finally able to visit her and thank her for her service to the Union cause, Elizabeth Van Lew raised the Union flag above her home for the first time in four years. Grant told her, “You have sent me the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.”

Richmond, Virginia

After the war, Van Lew needed a job to supplement what little was left of her family fortune. In 1869, President Grant rewarded Van Lew’s wartime service by appointing her postmaster of Richmond, a position she held during his two terms (1869-1877), helping to modernize the city’s postal system and employing a number of African Americans.

Van Lew also sponsored a library for African Americans that opened in Richmond in 1876, and she supported African American rights and women’s suffrage. She lost her position as postmaster in 1877, after Grant was defeated by Rutherford B. Hayes. She tried in vain to convince the federal government to reimburse her for the money she had spent on her espionage activities during the war.

Final Years

Van Lew lived out her days in the family mansion, but the citizens of Richmond never forgot about her support of the Union during the war. As an elderly lady, she was still treated as a pariah by Richmonders, who, according to her family doctor, “shunned her like the plague.”

Elizabeth Van Lew died nearly penniless on September 25, 1900, at the age of eighty-two. She was buried in Shockoe Hill Cemetery in Richmond. Her grave remained unmarked until the relatives of a soldier she had aided during the war donated a tombstone.

Van Lew’s work was highly valued by the United States. George H. Sharpe, the intelligence officer for the Army of the Potomac, credited her with “the greater portion of our intelligence in 1864-65.” In 1993 the U.S. government honored for her work in the Civil War with an induction into the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame in Fort Huachuca, Arizona. This organization was established in 1988 to honor soldiers and civilians who have made exceptional contributions to Military Intelligence.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Elizabeth Van Lew

Smithsonian.com: Elizabeth Van Lew

Encyclopedia Virginia: Elizabeth Van Lew