Portland’s First Woman Physician

An advocate for women’s rights throughout her life, she first broke through the barriers to women in medicine while she was raising a family in Illinois. Later honored as one of Oregon’s pioneer doctors, Mary Anna Cooke Thompson practiced medicine in Oregon for more than forty years.

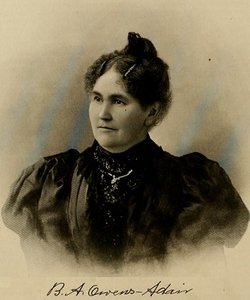

Image: Dr. Mary Anna Cooke Thompson

Courtesy Joseph Gaston

Portland: Its History and Builders

Early Years

Mary Anna Cooke was born February 14, 1825 in New York City. Her parents, Horatio and Anna Bennett Cooke, were both from England. The Cooke family moved to Chicago, Illinois when Mary was twelve.

Mary fell in love with a carpenter from Pennsylvania named Reuben Thompson; she married him on November 14, 1848. The couple moved to La Salle, Illinois, where they lived for the next eighteen years. During that time, Mary gave birth to five children – three sons who survived, two daughters who died. They later adopted a niece.

Blazing a Trail for Female Physicians

Most medical schools were closed to women; therefore, Thompson persuaded two local physicians to let her study with them. With Dr. Francis Bry and Dr. Lyman Larkin as her tutors and their practices as her clinics, she prepared to become one of the first woman practitioners in Illinois. Her main field of study was women and their infants, and she insisted on sanitary conditions and rest during childbirth.

In 1866, Mary Anna Cooke Thompson traveled with her husband and children to Oregon by ship through the Isthmus of Panama. In Portland – a town of about 6,600 – they reunited with Mary’s parents and several of her siblings who had emigrated from Chicago before the Civil War.

Dr. Thompson opened a medical practice, resumed work for women’s rights, and participated in the temperance movement. In addition to the Thompson’s three sons and their adopted daughter, Libbie – Thompson gave birth to her last child, James, in Portland in 1871, when she was forty-six.

Oregon’s First Generation of Women’s Rights Activists

An 1878 Oregon statute allowed citizens who were at least twenty-one-years-old, who owned property and had lived there thirty days or more “upon which he or she pays a tax” could vote in school elections. While this law did not consider marital status as a requirement, many Oregon women continued to be excluded from voting because they were legally barred from owning property separate from their husbands.

Inspired by Susan B. Anthony, Anna Howard Shaw, and other prominent members of the national women’s suffrage movement, Oregon’s early suffragists in 1873 formed the Oregon Woman Suffrage Association.

Image: Abigail Scott Duniway

Oregon’s leading feminist and author

Abigail Scott Duniway

Feminist Abigail Scott Duniway took an early role in Oregon’s campaign for the franchise. Duniway’s role as a journalist allowed her to use her newspaper, the New Northwest (1871-1887), to publicize the cause and to build networks with local and national readers. She also attended national suffrage conventions and gave speeches about women’s right to vote, which she viewed as part of a broad campaign to achieve equal economic and social rights for women.

Alongside her friends Dr. Bethenia Owens-Adair and Frances Fuller Victor, Mary Anna Thompson committed herself to the temperance and prohibition movements. Thompson also became active in the women’s suffrage movement in Oregon.

Dr. Bethenia Owens-Adair

Bethenia Owens-Adair overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles to become a social reformer and one of Oregon’s first women doctors with a medical degree. Some Oregon women – like Dr. Mary Anna Cooke Thompson – called themselves “doctor” although they had not attended medical school and did not possess degrees. A few others, such as Owens-Adair and Mary Avery Sawtelle, earned medical degrees and established early practices in Oregon.

Owens-Adair confessed in her autobiography: “The regret of my life up to the age of thirty-five was, that I had not been born a boy, for I realized very early in life that a girl was hampered and hemmed in on all sides simply by the accident of sex.” However, she persevered and graduated from the Eclectic Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1874. She followed that up by earning a second medical degree from the University of Michigan in 1880.

Image: Dr. Bethenia Owens-Adair

Owens-Adair practiced medicine in several Oregon counties, and in North Yakima, Washington, where her son George was a practicing physician. She offered medicated vapor baths and electricity to her patients as treatments for rheumatism and other chronic diseases. Later, she specialized in the treatment of women and children.

Owens-Adair was passionately involved in reform movements. The effects of alcohol in her family drew her to work in the temperance movement. She argued for women’s suffrage as well as women’s education, employment, and health.

Thompson’s Speaking Tour in the East

In 1877-1878, during a nine-month speaking tour in the East, Dr. Mary Anna Cooke Thompson participated in the National Woman Suffrage Association Convention in Washington, DC and lectured on a variety of reform topics. As the “noble representative woman from Oregon,” she met with leaders such as Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In January 1878, California Senator Aaron A. Sargent unsuccessfully introduced a bill on the floor of the United States Senate calling for a women’s suffrage amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The bill would be introduced each year for the next forty years. The twenty-eight words in Sargent’s bill would finally become the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States in 1920:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Mary Anna Thompson was one of thirteen women who addressed the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections in support of Senator Sargent’s bill. Her speech on January 12, 1878 underscored her belief in the moral superiority of women and their ability to stem the tide of corruption if given the ballot.

She called on President Rutherford B. Hayes at the White House to ask for his support and visited with co-workers and friends Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone. By the time she returned to Portland in July 1878, Thompson had given at least forty speeches.

Late Years

After losing in an effort to gain the right to vote by an initiative in 1906 and 1908, Oregon suffragists tried a different approach in 1910: an initiative giving only female taxpayers the right to vote, but that failed as well. Finally, in 1912, suffragists led by Abigail Scott Duniway won their long struggle: their measure passed by a margin of 61,265 in favor to 57,104 against. Despite the law’s passage, many women still did not have the right to vote – due to other legal restrictions – until the 19th Amendment was written into the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920.

In 1910, at age eighty-five, Mary Anna Cooke Thompson still listed herself as a doctor. She died in Portland on May 4, 1919, six months after suffering a paralytic stroke.

SOURCES

Mary Anna Cooke Thompson

Oregon Encyclopedia: Mary Anna Cooke Thompson

Oregon Historical Quarterly: Dr. Mary Anna Cooke Thompson