Slaves Seeking a Place to Live Free

Image: Plymouth Church

Brooklyn, New York

Thousands of people escaped bondage on the path from slavery to freedom called the Underground Railroad (UGRR) that ran through New York City. Sometimes the ships in the harbor carried slaves who slipped ashore and filtered into the population of the largest city in the country. Several Brooklyn churches participated in the UGRR; Plymouth Church was called its Grand Central Depot.

Plymouth Church

The Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims was founded in 1847, and its first pastor was Congregationalist minister Henry Ward Beecher, brother of the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Reverend Charles Ray, an African-American living in Manhattan and the founding editor of the Colored American newspaper, stated that he “regularly drop off fugitives at Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn.” Beecher was quoted as saying:

I opened Plymouth Church, though you did not know it, to hide fugitives. I took them into my own home and fed them. I piloted them, and sent them toward the North Star, which to them was the Star of Bethlehem.

A Pro-Slavery City

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the city’s banking and shipping interests were closely tied to the cotton and sugar trades, industries that relied on slave labor. The abolition of slavery would significantly damage New York City’s position as the financial capital of the United States. These were strong alliances that would not be given up easily, but the Underground Railroad continued to operate throughout the city.

As historian Eric Foner details in his book, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, New York was an important station for those passing through on their way to Canada. Between 1830 and 1860, a relatively few New Yorkers, black and white, assisted more than 3,000 fugitive slaves escape bondage.

Sydney Howard Gay

In the 1850s, Sydney Howard Gay was the editor of the weekly abolitionist publication, the National Anti-Slavery Standard, the official weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society, which was founded in 1833 by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Gay was also a key operative in the Underground Railroad in New York City through his printing office.

For unknown reasons, Gay began interviewing the runaways who passed through his office in the 1850s and wrote down their stories. Keeping these records was extremely dangerous. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 had made helping fugitive slaves illegal. He told how and why they escaped, who helped them along the way, and where they went after leaving the city. The resulting two notebooks, which he called the Record of Fugitives, contain information about more than two hundred men, women, and children.

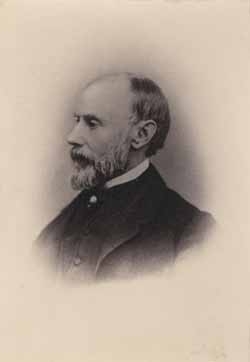

Image: Sydney Howard Gay

Louis Napoleon was a black porter who worked in Sydney Gay’s office; he met the freedom seekers when they arrived in New York City. Among the many slaves Napoleon and Gay assisted were three famous fugitives: Henry Box Brown, Jane Johnson, and Harriet Tubman.

This is an interesting excerpt from page four of the Record of Fugitives:

July 24th. Recd a note from J. S. G. [James Sloan Gibbons] who had received information that one Sarah Moore a colored woman, & a fugitive slave living at New Haven, was in danger of capture, & there was reason to suppose that her husband Jacob Moore had betrayed her. Napoleon was sent in the next train to New Haven with directions to find the woman & take her immediately to Albany. Napoleon arrived at New Haven, & found Sarah without difficulty. She had a comfortable room well furnished at her own cost, for her husband had abandoned her some time since, & become a worthless fellow. In the morning they started for Albany but at the depot Napoleon saw a N.Y. marshal well known to him, the same, who about a year since, arrested & returned to slavery the brother & nephews of Dr. Pennington, & with him was a man who answered to Sarah’s description of her master. Napoleon was, naturally enough, a good deal alarmed, & thought it best to leave the train at Springfield. There they remained – Sarah had an infant child with her – a day & a night; and the following day went to Albany.

Image: The Gibbons Family in 1854

Standing: William, Sarah, and Julia

Seated, Lucy, Abigail and James Gibbons

Credit: Daniel Bernauer, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College

Abigail Hopper Gibbons

In 1833 Quaker abolitionist Abigail Hopper married James Sloan Gibbons. They were dedicated abolitionists and philanthropists who devoted their lives to improving those of others. The couple lived in Philadelphia until 1835 when they moved to New York City where she started a school for African-American children in her home and volunteered at a school for African-American adults. James was a banker and first worked for the Bank of the State of New York.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Abigail and James Gibbons made their home on West 29th Street in Manhattan an established stop on the Underground Railroad and a center for traveling abolitionists. There were often several escaping slaves in residence, and they were given whatever aid they needed. Several entries from the letters of their family friend Joseph Choate verify this:

The house of Mrs. Gibbons was a great resort of abolitionists and extreme antislavery people from all parts of the land, as it was one of the stations of the Underground Railroad by which fugitive slaves found their way from the South to Canada. I have dined with that family in company with William Lloyd Garrison, and sitting at the table with us was a jet-black Negro who was on his way to freedom. …

The Gibbons home was targeted during the New York City Draft Riots of July 1863, as James Gibbons explains in a letter to a friend:

You will see by the papers that our house has been sacked. Our daughters saved most of their best clothing by previous removal. Everything taken. If you have any means of communication with Mrs. Gibbons, please say we are all well and in jovial spirits. It is our contribution to the war.

In the book, Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery: New York’s Buried Treasure, there is a passage devoted to New York City’s Civil War Riots of July 1863:

The homes of abolitionists and Republicans became prime targets of the mobs. On July 14, at about noon, two men on horseback, shouting and waving swords, lead a mob against the home of abolitionists Abigail Hopper Gibbons and James S. Gibbons near Eighth Avenue and 29th Street. The Gibbons’ two daughters fled to a neighbor’s house as men with pickaxes stormed in and destroyed what they could. Other rioters joined in, looting and smashing what remained, only to be driven off twice by soldiers and police, and to return a third time to set the house on fire. Neighbors, concerned that the fire might spread to their houses, extinguished the flames.

The Gibbons sisters escaped the mob by climbing over the rooftops of neighboring buildings and then descended through the house at No. 355 and boarded a carriage on Ninth Avenue. Daughter Julia wrote this after the ordeal:

Father, Lucy, and I are staying with the Choates [Joseph H. Choate]. … The rioters yesterday gutted our house completely. We had time to save most of our valuable clothing … and a few other valuables, but the furniture is all gone and most of the pictures, all the books &c. We had only a few hours to scratch together what we did save. … We had scarcely been out of the house fifteen minutes when the rabble came. …

We are so glad to get off with our lives and dearest possessions, that we can only be satisfied with the result. Many lives have been endangered, and our just having left the house, and father having been out of the neighborhood, are such fortunate circumstances that we can regret nothing. …

Lucy Gibbons described the damage done to the house in a letter to her Aunt Anna:

They destroyed and carried off everything, throwing bureaus and other pieces of furniture from the windows; setting fire to the house in many places; and leaving it completely stripped. The front door was broken in, marble mantle pieces broken down, gas and water fixtures twisted off, (the leaders took the precaution to have the water and gas turned off in the cellar,) banisters, window sashes, closet shelves &c. carried away, and every scrap of oil-cloth torn from the floors.

Abigail Hopper Gibbons was not there when her home was looted and defaced by the mob. She was somewhere in the South caring for wounded soldiers. In addition to her great work in the abolitionist movement and prison reform, she received much recognition as a nurse and relief worker during the American Civil War. In her obituary, she was referred to as “one of the most remarkable women of this century.”

David Ruggles

Freed slaves and fugitives lived among Irish and German immigrants in an area known as Five Points, an overcrowded, unsanitary slum. In and around this enclave existed a clandestine community of abolitionists and enlightened individuals helped runaway slaves escape to a place where they could live free; their network of Underground Railroad stations stretched across the city.

Image: David Ruggles Home

36 Lispenard Street, Tribeca

New York City

David Ruggles was born free in Connecticut around 1810 and came to New York City at age 17 and quickly became an activist in the abolitionist movement. As a stationmaster on the UGRR, Ruggles helped several hundred escaped slaves find freedom, including famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. At the bookstore and library he ran out of his home, Ruggles printed and distributed anti-slavery pamphlets and newspapers – and a magazine he called the Mirror of Liberty, the first African American magazine.

SOURCES

Lamartine Place Historic District – PDF

Secret Lives of the Underground Railroad

Sydney Howard Gay’s Record of Fugitives

Manhattan’s Underground Railroad Station

Untapped Cities: 10 Stops on the Underground Railroad in NYC

Smithsonian: The Little-Known History of the Underground Railroad in New York