Business Women in the Early United States

Women have always struggled with the challenges presented by socially-determined gender roles, which have both created opportunities for women’s advancement and limited their growth as professionals.

Image: Eliza Lucas Pinckney

Eliza Lucas Pinckney

Business: Agriculture

Eliza Lucas (1722-1793) was born in Antigua, West Indies and grew up at one of her family’s sugarcane plantations on the island. Her parents, Lt. Colonel George Lucas and his wife Ann sent all their children to London to be educated. Eliza studied French and music, but her favorite subject was botany.

Eliza’s mother died shortly after they moved, and in 1739 Colonel Lucas had to return to his military post in Antigua, leaving sixteen-year-old Eliza in charge of three family plantations – a total of 5100 acres. The Colonel sent Eliza various types of seeds for trial on the plantations from Antigua. She recorded her decisions and experiments with those plants in a letter book, which is one of the most impressive collections of personal writings by an eighteenth-century woman in America.

In 1739, she began experimenting with the indigo plant, which the expanding textile industry used for dyes. In experimenting with growing indigo in new climate and soil, Lucas also used the knowledge of enslaved Africans on the plantations who had grown indigo in the West Indies and West Africa.

After three years of many failed attempts, Eliza proved that indigo could be successfully grown and processed in South Carolina. Her father hired an African indigo processing expert from Montserrat in the French West Indies, and his expertise was most helpful.

Lucas proved that colonial planters could make a profit in the extremely competitive market. The volume of indigo dye exported increased dramatically from 5,000 pounds in 1745-46, to 130,000 pounds by 1748. Indigo became second only to rice as the South Carolina’s cash crop, and contributed greatly to the wealth of its planters.

In 1744, Eliza Lucas married politician Charles Pinckney, and their family expanded by four: three sons and a daughter. Eliza raised her family, kept her agricultural business, and even found time to spy for the Colonial army during the Revolutionary War. Remembering her contributions to her country, President George Washington asked to be a pallbearer at Eliza’s funeral in 1793.

For her contributions to South Carolina’s agriculture, the membership of the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame inducted Eliza Lucas Pinckney into their fellowship in 1989, the first woman to be so honored.

Mary Katherine Goddard

Business: Journalist, Printer and Publisher

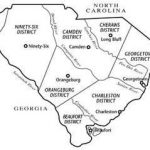

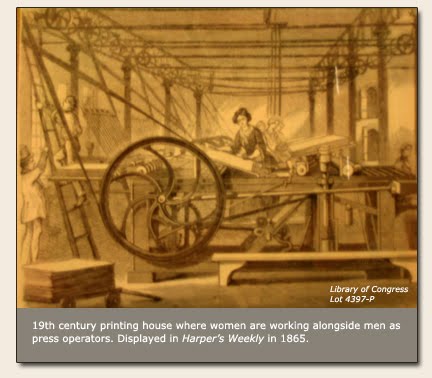

Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816) was living with her family in New London, Connecticut in 1757 when her father died , leaving a valuable estate. When Mary Katherine’s brother William came of age in 1762, they moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where her mother Sarah Goddard lent her son the money to open a print shop – the first in that colony.

Although William was in charge of the printing business, he traveled a great deal, and Sarah Goddard was the true publisher of the Providence Gazette and Country Journal. Mary Katherine was very active in the business and avoided the usual activities for young ladies to work as a typesetter, printer, and journalist. The mother/daughter team established a popular printing and publishing business at a time when newspapers exerted great political influence.

William left for Philadelphia in 1765, where he began another print shop and newspaper; the women joined him there in 1768 and helped run the Philadelphia Chronicle and Universal Advertiser. Sarah Goddard died in 1770, leaving Mary Katherine to manage the large printing office. She managed the monumental project of printing the first copy of the Declaration of Independence that included the signers’ names.

Her brother’s printing business took her to yet another city: Baltimore. While the business belonged to her brother, Mary Katherine ran every aspect of the company, including publishing Baltimore’s first newspaper, The Maryland Journal. The business flourished under Mary Katherine’s leadership. A year later, she was officially named publisher of the newspaper.

William was never successful at any venture, and he was jealous of his sister’s business acumen. In 1784, Mary Katherine’s name disappeared from the newpaper; historians believe that William most likely forced his sister to leave the business. Records indicate that she filed five lawsuits against him.

In 1789, Mary Katherine Goddard became the first woman in America to open a bookstore and spent the remaining years of her life running the shop in Baltimore.

Rebecca Lukens

Business: Iron and Steel Manufacturing

Rebecca Lukens (1794–1854) was the owner and manager of the iron and steel mill that grew into the Lukens Steel Company of Coatesville, Pennsylvania. Rebecca’s father Isaac Pennock established the Federal Slitting Mill near Coatesville, Pennsylvania in 1793. In 1810 he purchased the Coates farm along the Brandywine River and converted the sawmill on the property into the Brandywine Iron Works and Nail Factory.

Image: Rebecca Lukens

Soon after, Rebecca traveled to Philadelphia, where she met and fell in love with Dr. Charles Lukens. They were married on March 23, 1813. Lukens soon left his medical practice joined his father-in-law in the iron business. After several years, Pennock bought the business and then leased it to his son-in-law.

Boilerplate is steel that is formed into thin, flat pieces – one of the fundamental forms used in all metalworking. In March 1825 the Brandywine Mill received an order for enough boiler plate to build the first iron-hulled steamboat in America. Charles Lukens did not live to see their first order of boilerplate completed. In 1825 he fell ill and died suddenly at the age of 39.

Rebecca Lukens inherited the company, becoming the first woman in the United States in the iron industry and the first female chief executive officer of an industrial company. The Widow Lukens was pregnant with her sixth child (only two daughters survived to adulthood), but she was deternined to keep the family business running at a critical point in its history.

Less than ten years later, the Brandywine Mill was thriving under her leadership. By 1834, her mill was a leader in the production of boilerplate for iron-hulled steamboats and railroads. The company also produced iron bands to make nails and barrel bands. In 1834 the entrepreneur expanded her business by opening a store, warehouse and freight agency.

Lukens also successfully steered her company through the national financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837, by relying on solid business principles, modernizing her mill, and refusing to slash iron prices.

More than 30 years after her death, Brandywine Iron and Nail became Lukens Iron and Steel, which was publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange until 1998, when it was purchased by Bethlehem Steel. In 1994, Fortune magazine posthumously crowned Lukens “America’s First Female CEO of an Industrial Company” and named her to the National Business Hall of Fame.

Marie Laveau

Business: Hairdresser and Voodoo Queen of New Orleans

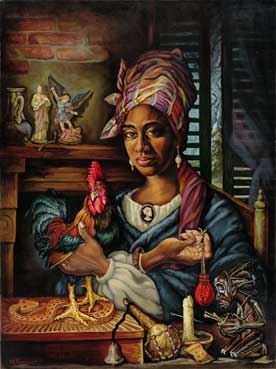

Marie Laveau (1794-1881) was born free in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, the daughter of a free Creole woman and the fifth Mayor of New Orleans, Charles LaVeau. Creoles are descended from the colonial settlers of French and Spanish descent in Louisiana.

Marie Laveau became a New Orleans hairdresser whose clients were wealthy white socialites, which allowed her to be privy to the rumors and gossip in the French Quarter. This wealth of information from both the elite women and their servants allowed her to convince people that she was a Voodoo priestess with magic powers.

Voodoo is a religious cult practiced in Haiti, parts of the Caribbean, and the southern United States that mixes beliefs and rites of African origins with elements of the Catholic religion. By 1830 Marie Laveau was one of several New Orleans voodoo queens, but she was deemed the most powerful. Her voodoo practice was highly lucrative. Under her guidance, Voodoo thrived as a business, served as a form of political influence, and provided a source of entertainment.

An astute businesswoman, Laveau was the first commercial Voodoo Queen, specializing in romance and finance. All-knowing and all-powerful, she had great influence over her multiracial clientale, respected and feared by all. She introduced holy water, incense and Catholic prayers into the African-based Voodoo rites.

Image: Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau

Marie Laveau quickly came to dominance as the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans, taking charge of the public Voodoo rituals and ceremonies held at Congo Square, one of the few locations in rigidly segregated New Orleans where people of different races could mix freely. She ran other operations at the ‘Maison Blanche’ (the White House), which was built for secret voodoo meetings and liaisons between white men and black women.

Marie Laveau continues to be a central figure of Louisiana Voodoo and of New Orleans culture. Gamblers shout her name when throwing dice, and multiple tales of sightings of the Voodoo queen have been told. Her grave has more visitors than the grave of Elvis Presley. Although she is not yet officially considered a saint, there is a strong movement to have her canonized.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Eliza Lucas

Wikipedia: Rebeca Lukens

Wikipedia: Mary Katherine Goddard

TravelNOLA.com: The Facts about the Marie Laveau Legend

City of the Dead: A Journey Through St. Louis Cemetery #1 by Robert Florence (1996)