Abolitionist and Women’s Rights Activist

Ann Carroll Fitzhugh Smith and her husband Gerrit Smith were wealthy activists and philanthropists who committed themselves to the movement to end slavery in 1835. They were prominent members of antislavery societies in New York State and on a national level.

This house was a refuge for the many escaped slaves who received food and comfort on their journey to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Early Years

Ann Carroll Fitzhugh was born January 11, 1805. Her father William Fitzhugh, a colonel in the Continental Army, built a home near Chewsville, Maryland which he called The Hive because of the many activities carried on by his twelve children and the work necessary to sustain life in the surrounding wilderness. Fitzhugh left Maryland for New York, where – along with Colonel Nathaniel Rochester and Charles Carroll – he purchased the “100-acre Tract” at the Genesee Falls that would become the city of Rochester.

Marriage and Family

In 1822, Ann Carroll Fitzhugh of Rochester, New York married Gerrit Smith (1797-1874) of Peterboro, New York. Ann and Gerritt Smith had seven children, five of whom died young. Their surviving children were Elizabeth (1822–1911) and Greene (1842–1886).

The Smiths lived in a large frame house facing Peterboro Green, Gerrit’s lifelong home. It was a hall and parlor style house, with a large central hall front to back. One side of the central hall comprised a library which contained approximately 2,000 books, a kitchen, and a dining room. A conservatory and a parlor were on the other side of the hall.

Abolitionists

As a child growing up in Chewsville, Maryland, Ann Carroll Fitzhugh had been given a slave, Harriet Sims, who was later sold to a slaveholder in Kentucky, with her spouse Samuel Russell. After they were married Ann and Gerrit Smith located the Russells; they purchased their freedom and settled them into a home at Peterboro. The Smiths’ fierce opposition to slavery prompted Henry Highland Garnet to say:

There are yet two places where slave holders cannot come, Heaven and Peterboro.”

With his liberal beliefs and wealth, Gerrit Smith was one of the most powerful abolitionists in the United States. Scores of abolitionists received comfort and support at the Smith home. The Smiths purchased the freedom of hundreds of African Americans and arranged for the safe passage to Canada for many others. After 1835, the two would not serve food grown with slave labor.

In 1834, Smith founded a manual labor school for “young men of color” in Peterboro. Several of the students attended the October 22 meeting. Their names appear in the official proceedings of the New York State Anti-Slavery Convention and State Society for 1835. Several of these students became ministers, orators, and/or poets.

In the fall of 1835, members of the anti-slavery movement in the state of New York announced that they planned to establish a state society. Notices went out for the first meeting would be held on October 21 at the Second Presbyterian Church in Utica, New York, where six hundred antislavery advocates assembled. While the meeting was in progress, eighty or so men pushed their way into the church with cries of “Open the way! Break down the doors! Damn the fanatics!”

The meeting came to an abrupt end, but Ann and Gerrit Smith were in the audience and offered to host the meeting the following day in Peterboro. About three or four hundred delegates accepted Smith’s offer and made their way to Peterboro, but their trip was not easy. Slavery sympathizers placed logs across the roads, and they pelted the abolitionists with mud, eggs, clubs, and stones.

James Caleb Jackson, along with one hundred and two other abolitionists traveled by the Erie Canal to Canastota and then walked the ten miles to Peterboro. They were not hindered during their journey, but bystanders were puzzled by their presence. One woman asked, “What is the matter; is war declared?” Jackson responded:

Yes, war to the death against slavery. … We have begun the grandest revolution the world has ever seen; and if we do not die, we mean to see that revolution accomplished, and our land free from the tread and fetter of the slave.

The October 22 meeting of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society was held in the Peterboro Presbyterian Church.

Ann Carroll Fitzhugh Smith enjoyed a financially secure life except for a short time during the Panic of 1837. That year her family moved from their mansion to a cottage, and she and her daughter Elizabeth worked as clerks in Gerrit’s land office. Except for that brief period during the Panic of 1837, Ann Smith lived her life in fine houses that were known as centers of hospitality and philosophical discussion.

While her daughter Elizabeth attended a Quaker school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Ann stayed in the city for extended periods during 1836, 1837 and 1839. During that time, Ann was welcomed into the prestigious circle of abolitionists that included James and Lucretia Mott, C.C. Burleigh and Mary Grew. Ann and her daughter taught Sunday school in one of Philadelphia’s African-American communities.

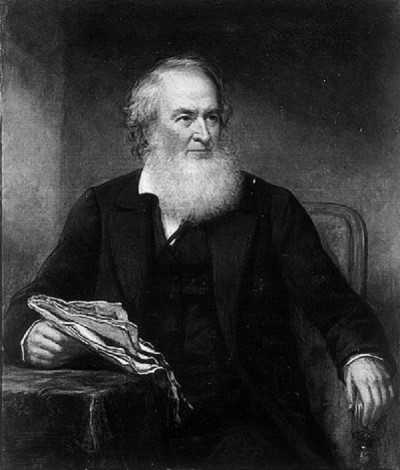

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith’s father Peter was a partner of John Jacob Astor. He was one of six children born to Peter and Elizabeth Livingston Smith. Gerrit inherited significant wealth from his father, and he was a shrewd businessman. Gerrit bought the land his siblings had inherited, making him one of the largest landowners in the United States.

Image: Gerrit Smith

No image of Ann Carroll Fitzhugh Smith available

Smith often used his personal funds to help those who were charged with crimes under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793; he also provided funds to friend and abolitionist Frederick Douglass to keep his newspaper The North Star running. He gave hundreds, if not thousands of land to provide homes and gardens for former slaves; it has been said that he contributed more than $8,000,000 to causes he supported.

A benefactor of two large failed slave escapes – the Pearl Incident and John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry – as well as numerous projects in the African American community, Gerrit Smith also supported women’s suffrage. He also gave speeches against the injustice of slavery and racial and gender equality.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Linked by his maternal aunt, Gerrit Smith’s cousin was a well-known women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Gerrit introduced her to her future husband, Henry Stanton, at the Smith family home. Gerrit was partially responsible for Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s view of slavery as he arranged for a slave girl and his cousin to meet, illustrating to her the horrors that he and Henry Stanton were trying to eradicate.

During her childhood Stanton “spent weeks every year” in Peterboro, engaging in “discussions on every possible phase of political, religious, and social life….” She noted that, “the rousing arguments at Peterboro made social life seem tame and profitless elsewhere….” She wrote:

Here one was sure to meet scholars, philosophers, philanthropists, judges, bishops, clergymen and statesmen. …There never was such an atmosphere of love and peace, of freedom and good cheer, in any other home I visited.

Underground Railroad

What was not widely known at the time was that Gerrit and Ann Smith’s Peterboro home was a station on the Underground Railroad, and they played a crucial role in its operations during the 1840s and 1850s. Ann Fitzhugh Smith frequently traveled in an enclosed carriage and allowed her carriage to be used to convey veiled fugitives on their way to Canada.

The Smith family’s extensive land holdings in New York were managed at the Land Office on the grounds of their estate. Out of the Land Office, Gerrit Smith sold farm tracts for one dollar each to at least 3000 poor African Americans; he transferred approximately 140,000 acres being transferred betwen 1846 and 1850.

New York State Anti-Slavery Society returned to Peterboro for its convention on January 19 and 20, 1842. At this meeting Gerrit Smith encouraged the slave to “take [what] is absolutely essential to your escape, the horse, the boat, the food, the clothing, which you require.” Smith believed that slave’s lives were taken from them in service of another; it was, therefore, right and just that they take whatever they needed to gain their freedom.

Elizabeth Smith Miller

Only two of the Smiths’ children lived to adulthood, the most prominent being their daughter, Elizabeth Smith Miller. Elizabeth was educated mainly by her father and governesses, except when she attended a “manual labor school” in Clinton, New York, and in 1839 when she went to the Friends School in Philadelphia.

In 1843, at the age of twenty-one, Elizabeth married Charles Dudley Miller, a lawyer. The Millers had four children born between 1845 and 1856; after the wedding, they lived in Cazenovia, New York and then in Peterboro. They finally settled in 1869 at Lochland, a lakefront estate in Geneva, New York.

After becoming “thoroughly disgusted with the long skirt” while working in her garden, Elizabeth Smith Miller designed what would become known as the Bloomer Costume in the early 1850s. She described the outfit as “Turkish trousers to the ankle with a skirt reaching some four inches below the knee.” Shortly after designing the dress, Miller showed it to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose friend Amelia Bloomer also donned the costume and publicized it in her paper, the Lily, the first American newspaper edited by and for women.

Many women’s rights activists donned the outfit, but they were ridiculed and after a few years, many stopped wearing the costume. Miller wore Bloomers for seven years – at receptions and dinners in Washington, DC during her father’s term in Congress (1852-1853). The tradition was carried on for several more years, however, in gymnasiums and sanitariums.

Image: Elizabeth Smith Miller (right) with her daughter Anne

Miller’s reform activities, including her advocacy for women’s rights, lasted throughout her life. As early as 1850, she and her husband signed the Call for the first National Woman’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1878, she acted as an Ontario County delegate to Rochester’s thirtieth anniversary celebration of the first woman’s rights convention, sponsored by the National Woman Suffrage Association.

The marriage between Ann Carroll Fitzhugh and Gerrit Smith lasted until their deaths, which followed in rapid succession. Gerrit Smith died on December 28, 1874 while they were staying in New York City. After tending to family affairs in Manhattan, Ann returned to the Peterboro home.

Ann Carroll Fitzhugh Smith died at the Peterboro mansion on March 6, 1875, the day that Gerrit would have been 78 years old.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Ann Carroll Fitzhugh

Shackles of Yesterday: Gerrit Smith

National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum

NPS.org: Gerrit Smith Estate and Land Office

Western New York Suffragists: Elizabeth Smith Miller