Painter, Illustrator and Pen and Ink Artist

Eliza Greatorex was a noted painter of landscapes and cityscapes; she was especially known for her pen and ink drawings of New York and European scenes. She was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Design, one of America’s first women illustrators, and one of the earliest women artists to reproduce scenes of Colorado in pen and ink drawings.

Image: Portrait of Eliza Pratt Greatorex

By Ferdinand Thomas Lee Boyle (1869)

Credit: National Academy of Design, New York

Early Years

Eliza Pratt was born December 25, 1819 in Manorhamilton, Ireland, and she emigrated to New York City with her family in 1840. In 1849 she married Henry Wellington Greatorex, a composer of hymns such as “Praise God From Whom All Blessings Flow.” They had two daughters, Eleanor and Kathleen, and a son Thomas, who died in Colorado in 1881 at about the age of thirty. The Greatorexes traveled throughout North America and Europe while Henry performed in concerts.

Daughters Kathleen and Eleanor never left their mother’s side and never married; they studied art in New York and Europe and became prominent artists. Both sisters decorated china, illustrated books and painted. Many of Kathleen’s paintings were of flowers: The Last Bit of Autumn (1875); Goethe’s Fountain, Frankfort (1876); panels with Thistles and Corn (1877); and Hollyhocks (1883). Eleanor exhibited paintings at the National Academy of Design: The Bath (1884), and Color that Burns as if no Frost could Tame (1885).

Eliza kept a comfortable home and began creating artwork. By 1855, the National Academy of Design in New York City was exhibiting her pen and ink drawings.

Widowhood

In 1858, Henry Greatorex died suddenly in Charleston, South Carolina, just after they returned from England. Eliza was a widow with three small children at the age of 39. Eliza returned to New York bravely carried on. To earn a living and support her young children, for the next fifteen years she worked as a teacher at an art school.

To further her own career in art, she opened a studio on Broadway and began studying landscape painting with Hudson River School painters James and William Hart and with William Wotherspoon, who had studios nearby. Between 1861 and 1862, she was in Paris with her daughters and studied with Emile Lambinet. In 1868, they spent time in Italy, but Eliza’s health was too fragile to allow her to paint, and she turned exclusively to sketching.

For the next fifteen years – approximately 1861 through 1876 – Eliza Greatorex traveled extensively, mostly in Europe, always returning to New York City. Whatever the location, she was always working. Her artwork appeared in a National Academy of Design annual in 1862, and she was represented in every annual through 1884, except on a few occasions when she was abroad.

Associate of the National Academy of Design

The National Academy of Design in New York City elected Eliza Greatorex an associate in spring 1869, the only living female so honored. The Academy is an honorary association of American artists founded in New York City in 1825 to “promote the fine arts in America through instruction and exhibition.” There were no art schools and few public galleries in New York at the time, and the founders intended for the Academy to serve as a school for aspiring professional artists.

This excerpt from the Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center tells us exactly what an independent woman Greatorex had become:

Greatorex arranged with Ferdinand Thomas Lee Boyle to paint the requisite diploma portrait. Although Boyle painted the likeness, his sitter surely dictated how she wanted to be presented. Her attire is simple, even severe: a dark, loose-fitting dress with long sleeves and a trim lace collar. She is shown standing in half-length and holding her pen in her right hand, which folds over her left, and rests both on a leather-bound portfolio presumably containing drawings done with the pen. She stands before us, a grey-haired woman of fifty with no pretense of vanity, but with an intensity of passion and vocation. The white quills catch the light, and call attention to the fact that she has replaced the traditional artist’s attribute, the paintbrush, with an ink pen.

She emphasizes its function as both personal emblem and symbol of power in the feminist arsenal, used not only for drawing but also for writing: the arena in which women had historically asserted themselves. Eliza had contemplated a career in letters before she settled on the visual arts, and combined studio arts with writing, including book publications on Germany and Colorado, as well as New York.

Once the portrait was complete, Greatorex gave it to the NAD, where it hung in the Summer 1870 exhibition. Then she and her children boarded the USS Hammonia bound for Germany, where they found lodging in Nuremberg, the hometown of German artist Albrecht Durer (1471-1528), where she made pen-and-ink drawings of the sites associated with his life. She was abroad from 1870 through 1873, in Germany and various locations in Italy.

Image:

Along the Shore in Autumn

Women in Art

In the early and mid-decades of the nineteenth century, women began traveling to witness the American landscape in the open air. Educators established schools to provide artistic education for young women, especially in landscape painting. Working with male artists or alone in their studios, they translated the beauty they saw in the countryside onto canvas. Many of these talented and accomplished women strived to become professional artists, but achieving this title was challenging.

These women exhibited their work at the National Academy of Design, the Brooklyn Art Association, the Artist’s Fund Society, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Some of these female artists supported themselves and their families through their art, including Fanny Palmer, a prolific lithographer for the Currier and Ives Company.

Eliza Greatorex managed to live reasonably well on artist’s wages. She kept a home in Manhattan and traveled with and without her brood on artist junkets to France, Germany, Algeria and Colorado. She sketched and published prints as they traveled.

While living in New York City, Greatorex and her children often spent summers with her sister upstate at Cornwall, where she sketched in oils along the Hudson and into the Highlands. She adopted the practices of Hudson River School artists, making preliminary sketches for paintings that she would complete the following winter in her studio.

In the mid-1860s, she began to apply the same methods to urban scenes. Instead of working in the countryside, she left her residence on Twenty-Third Street and set out every day to find a new place in the city to draw.

Although she began as a landscape painter, Greatorex apparently enjoyed creating collections of pen and ink drawings, which she then published in book form. Notable among her books were The Homes of Ober-Ammergau (1872); Summer Etchings in Colorado (1873); Etchings in Nuremberg (1875); and Old New York from the Battery to the Bloomingdale (1876). Through these publications, she acquired her reputation.

The American West

In the 1870s, Eliza received a commission to create a book of etchings of the Colorado mountains and landscapes in the Colorado Springs area. Artists traveling throughout the country in search of new subject matter was common in the post Civil War period, Greatorex, as a woman embarking on such an excursion, was exceptional.

Eliza recorded her Colorado experiences for publication, and the result of this trip was Summer Etchings in Colorado (1873). When she finished the project, she and her two daughters – both now becoming artists – once again traveled to Europe.

Scenes from her extensive travels were Greatorex’s dominant subject matter, presented in paintings, etchings, and especially in pen and ink drawings. From her sketches of colonial houses and other historic sites in New York City, she created a volume of reproduced drawings and paintings entitled Old New York from the Battery to Bloomingdale (1875). Several of those sketches were included in the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia in 1876.

Late Years

Beginning in 1878, Greatorex lived in Paris for several years, but in 1882 she returned to New York where she purchased a farmhouse and participated in the Cragsmoor Art Colony in Ulster County, New York. She and her daughters taught art classes there.

Then in 1885, Eliza Greatorex moved permanently to Paris where she died February 9, 1897 at age 78.

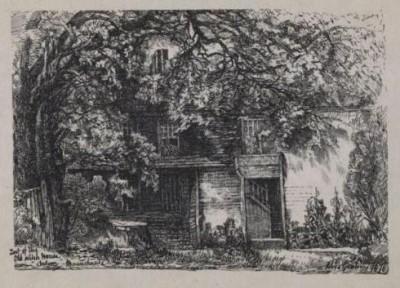

Image:

The Last of the Old Witch House

Eliza Greatorex, who was renown for her pen-and-ink sketches of American and European streetscapes, traveled to Salem, Massacusetts to sketch the Jonathan Corwin House.

Works

Eighteen of the sketches of New York were exhibited at the Centennial exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. Her large pen-drawing of “Durer’s House in Nuremberg” is in the Vatican in Rome. Among her paintings are View on the Housatonic (1863); The Forge (1864); Bloomingdale (1868); Chateau of Madame Oliffe (1869); Somerindyke House (1869); Bloomingdale Church, painted on a panel taken from the North Dutch Church, Fulton Street; St. Paul’s Church and The North Dutch Church, each painted on panels taken from these Churches (1876); Normandy (1882); and The Home of Louis Philippe in Bloomingdale, New York (1884).

Greatorex’s works were displayed in a 2010 exhibition by the Thomas Cole National Historical Site and Hawthorne Fine Art, entitled Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School.

SOURCES

AskArt: Eliza Greatorex

Wikipedia: Eliza Pratt Greatorex

The Lady with the Pen: The Graphic Art of Eliza Greatorex

New York Times: These Women Refused to Stay in the Kitchen

Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School – PDF