Slave Girls Searching for Freedom

In the seventeenth century, all slave states passed laws declaring that the children of an enslaved mother inherited her legal status. Mary and Emily Edmonson were two of fourteen children who survived to adulthood, all of whom were born into slavery in Maryland. In the late 1840s they became icons in the abolitionist movement.

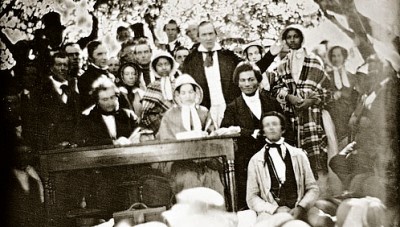

Image: Mary Edmonson (standing) and Emily Edmonson (seated), shortly after they were freed

Credit: Ipernity.com

Early Years

The Edmonson sisters were the daughters of Paul and Amelia Edmonson, a free black man and an enslaved woman. They were described as “two respectable young women of light complexion.” At the ages of 15 and 13, Mary (1832–1853) and Emily (1835–1895) were hired out to work as servants in two elite private homes in Washington DC; their wages were the sole income of Amelia’s mistress.

In April 1848, their brother Samuel Edmondson heard Mississippi Senator Henry Foote celebrating the recent French Revolution and the triumph of freedom. One of Samuel’s friends remarked:

… Senator Foote and all the rest of them [are] rejoicing that liberty and freedom from oppression have come to people thousands of miles away, while right here under the very sound of their voices, is a race of people who they themselves are holding in the very worst sort of human slavery.

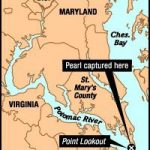

Escape on the Pearl

On April 15, 1848, teenagers Mary and Emily Edmondson, four of their brothers and seventy-one other slaves slipped quietly through the alleys and pathways of the District of Columbia. They were on their way to the Seventh Street Wharf where a sixty-five foot Chesapeake Bay Schooner named the Pearl was waiting. These slaves belonged to “41 of the most prominent families in Washington and Georgetown and were valued at $100,000.”

Word about the Pearl had spread quickly among free blacks and slaves and what began as an attempt to help seven slaves escape became a major operation, without the knowledge of the white organizers or crew. In the largest escape attempt ever, the plan was to sail the Pearl down the Potomac River and up the Chesapeake Bay to the Delaware River to freedom in New Jersey, a total of 225 miles.

The Pearl began its way down the Potomac, but the voyage was delayed overnight by the shift in tides and then squalls kept them from entering Chesapeake Bay. A passing steamer’s captain thought the Pearl looked suspicious and reported it to authorities.

In Washington the next morning, owners discovered that their slaves had escaped. They put together an armed posse of 100, who sailed downriver on a steamboat. They caught up with the Pearl at Point Lookout, Maryland, and towed the ship and its valuable cargo back to Washington, DC. The posse displayed the slaves in chains to whites as they passed the wharves at Alexandria.

An angry mob awaited the ship when it arrived in Washington City. Officials marched the male slaves in manacles across Pennsylvania Avenue to the city jail. Mary and Emily Edmonson walked behind their brothers with their heads held high.

Pro-slavery advocates rioted in the District for three days, attacking anti-slavery establishments and the printing presses of anti-slavery newspapers in an attempt to suppress the abolitionist movement. Rather than chance another escape attempt, most of the masters quickly sold the runaways to slave traders.

At the slave market in New Orleans, Mary and Emily were displayed on an open porch facing the street, hoping to attract buyers. Employees of the slave market handled the sisters roughly and used obscene language when speaking to them. However, when a yellow fever epidemic struck New Orleans, the slave traders quickly sent the girls back to Alexandria in order protect their investment.

Bruin’s Slave Jail

Slave dealer Joseph Bruin became notorious when he purchased many of the slaves who were unsuccessful in their bid for freedom aboard the schooner Pearl, including the Edmonson sisters. Bruin used a large brick Federal-style brick house at 1707 Duke Street in Alexandria, Virginia as headquarters for his slave trading operation. Another structure (no longer standing) behind the house was a holding facility for slaves who had not yet been sold. The Edmonson sisters worked at an on-site laundry there – washing, ironing and sewing; they were locked up at night.

Although the Constitution banned the slave trade from Africa in 1808, slave trading remained legal within the United States. Thousands of enslaved African Americans were sold by their owners in the east to the newly developing lands in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. And Bruin was in the thick of it.

Bruin eventually paid for his crimes against humanity. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Joseph Bruin fled Alexandria but was captured and then confined in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington. The Federal government seized his property, including his personal residence.

Henry Ward Beecher

Paul Edmondson continued his tireless campaign to free his daughters. Slave traders Bruin and Hill finally agreed to sell the sisters for $2,250. Edmonson traveled to New York and visited the members of the Anti-Slavery Society, who advised him to take his plea to the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, pastor of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York. Beecher was also an abolitionist, and he convinced members of his church to raise the funds required to purchase the Edmonson girls and free them.

Reverend Beecher’s church members in Brooklyn raised the necessary funds, and Paul Edmonson hurried back to Washington to purchase the girls’ freedom before they were returned to New Orleans.

Freedom, At Last

Mary and Emily Edmonson were emancipated on November 4, 1848, and their families gathered in Washington to celebrate this wondrous event. The Brooklyn church continued to contribute money to send the sisters to school. They enrolled in the interracial New York Central College in Cortland, New York and worked as domestic servants to support themselves.

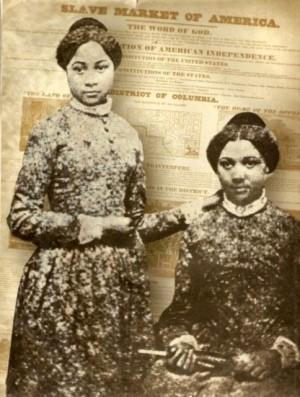

Fugitive Slave Law Convention

While studying at Cortland, the girls also participated in anti-slavery rallies in New York state. In August 1850 both sisters attended the Slave Law Convention in Cazenovia, New York to protest the Fugitive Slave Act, soon to be passed by Congress. Under this act, slave owners had unlimited powers to arrest fugitive slaves in the North and return them to slavery in the South. The convention, led by Frederick Douglass, declared all slaves to be prisoners of war.

Image: Edmonson Sisters at Fugitive Slave Law Convention

Cazenovia, New York

This meeting in August 1850 in Grace Wilson’s orchard made history; it brought together Frederick Douglass, Gerrit Smith, fifty or so fugitive slaves, and two thousand others to denounce the impending Fugitive Slave Act. This dreaded law would give slave owners the right to seize runaways in northern states and law enforcement officials were bound to help him do so.

Former slave Frederick Douglass is seated tot he right of the table and abolitionist Gerritt Smith (in dark coat and white shirt) is standing behind him. The Edmonson sisters are standing on each side of Smith (in white bonnets and plaid shawls). Douglass spoke about the recent arrest of abolitionist William Chaplin and expressed the need to petition for Chaplin’s release. Mary Edmonson, who spoke frequently at abolitionist meetings, agreed with Douglass and in a poignant speech she noted Chaplin’s kindness to her in the past.

Education at Oberlin College

With the continued financial support of Reverend Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mary and Emily Edmonson enrolled in the Young Ladies Preparatory Course at Oberlin College in Ohio in 1853. Since its founding in the 1830s, Oberlin had admitted blacks as well as whites, and was a center of abolitionist activism.

Six months after arriving at Oberlin, Mary Edmonson died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty.

Normal School for Colored Girls

Heartbroken, eighteen-year-old Emily returned to Washington DC and enrolled in the Normal School for Colored Girls, which trained young African American women to become teachers. Legendary educator https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2012/12/myrtilla-miner.html”>Myrtilla Miner had alarmed white citizens in 1851 by opening such a school in a city where slavery remained legal. The school prospered with contributions from Quakers and a gift from Harriet Beecher Stowe of $1,000 of the royalties she earned from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Miner stressed hygiene and nature study in addition to rigorous academic training.

In 1854, Myrtilla Miner wrote:

Emily and I lived here alone, unprotected, except by God. The rowdies occasionally stone our house in the evening. Emily and I have been seen practicing shooting with a pistol. The family [Paul and Amelia Edmonson] have come with a dog.

Duke Street in Alexandria, Virginia

Sculptor: Erik Blome

Harriet Beecher Stowe included part of the Edmonson sisters’ history, the Pearl Incident and other factual accounts of slavery in her book A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853). It was published to document the veracity of her depiction of slavery in her anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852).

Marriage and Family

By 1860, Emily Edmonson married Larkin Johnson. After living for twelve years in Sandy Spring, Maryland, Emily and her husband moved to Washington, DC. They purchased land in the neighborhood of Anacostia and became founding members of the Hillsdale community. Emily continued to work in the abolitionist movement and maintained her relationship with fellow Anacostia resident Frederick Douglass, even after the 13th Amendment. One of Emily’s granddaughters wrote:

Grandma and Frederick Douglass were like sister and brother – great abolitionists. I sat on his knee in his office in the house that is now a museum in Anacostia where we were born.

Emily Edmonson Johnson died on September 15, 1895 at her home on Howard Road.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Edmonson Sisters

Ipernity: Mary and Emily Edmonson

Archaeology at the Bruin Slave Jail – PDF

GoodReads: Fugitive Slave Law Convention

National Council of Negro Women: Saga of the Pearl – PDF

Her story has been told. I hope we never forget what happened to Africans and I pray that it never happens again.