First Woman Clipper Ship Commander

Mary Ann Brown Patten was the first woman commander of an American Merchant Vessel at the age of nineteen. Her husband, the ship’s captain, was severely ill with fever, and the first mate was attempting to incite a mutiny among the crewmen. Her clipper ship Neptune’s Car was ten thousand miles away from its starting point at New York when she faced the unforgiving winds of Cape Horn on the southern tip of South America. And then on to San Francisco, where clients were waiting for her cargo.

Image: Mary Ann Brown Patten

Mary Ann Brown married sea captain Joshua Patten in 1853 when she was 16. He was 25, and was ferrying cargo and passengers from New York to Boston. In 1854, Joshua Patten was offered the chance to sail the merchant ship Neptune’s Car from New York to San Francisco, through Cape Horn, one of the most dangerous straits in the Western Hemisphere. Reluctant to abandon his young wife, Joshua received permission to bring Mary along on the voyage. With just a matter of hours to prepare, the couple departed on their first trip together.

Neptune’s Car was a clipper ship measuring 216 feet long, 40 feet wide and more than 23 feet tall. During the voyage, Joshua taught Mary the basics of navigation, meteorology, the ropes and sails, and other seamen’s duties. Mary had received an excellent education from her well-to-do Boston family, and, with little else to occupy the long days at sea, she looked after her husband and began to study navigation in depth. The trip was uneventful.

A Friendly Race

Along the New York waterfront on July 1, 1856, as the ship was prepared for departure, temperatures were in the upper 90s by noon as sailors sluggishly prepared their vessels to head out to open water and cooler temperatures away from shore. Captain Patten was boasting that his ship would race against the clippers Intrepid and Romance of the Seas from New York to California. Typically a four-month, 15,000-mile journey, he claimed that he would make it in less than 100 days. Since the captain had a reputation for fast voyages, he was the instant favorite to win.

However, everyone would soon learn that Patten’s first mate had severely fractured his leg and was unable to sail. The ship’s owners, Foster and Nickerson Company, refused to delay the voyage until Captain Patten could find a suitable replacement. Their valuable cargo of machinery and supplies for the California gold-mining camps could not wait, and they were guaranteed high profits if the ship arrived in San Francisco quickly. Foster and Nickerson signed a man named Keeler as a substitute first mate and demanded Neptune’s Car leave on time.

The captain’s attractive 19-year-old wife, Mary Ann Brown Patten, was slender and petite with long brown hair and dark eyes. A small crowd gathered along the wharf to watch as the harbor pilot boarded Neptune’s Car as it was towed down the East River past Sandy Hook, New Jersey. The few women standing on the wharf waved goodbye to the girl who stood on the ship’s deck. Unbeknownst to all except her husband, Mary was pregnant with their first child.

When the ship was safely away from the docks, the harbor pilot departed, and Captain Patten ordered his men to hoist the sails. Romance of the Seas had left the day before and Intrepid was close behind. With Mary by his side on the quarterdeck, Captain Joshua Patten believed he could win the race. Any man would be proud to command Neptune’s Car. Long and sleek, the clipper was 216 feet long, had a 40-foot beam and could carry 1,616 tons of cargo. The tallest of its three masts stretched 20 feet above the deck, and it carried 25 sails, the largest of which spread some 70 feet across.

Image: New York City’s East River, 1848

A thicket of masts and rigging rises above vessels docked at New York’s East River wharves, From here Neptune’s Car was towed downriver past Sandy Hook, New Jersey, where it began its fateful journey around Cape Horn and on to San Francisco.

Clipper ships had been used in worldwide commerce for many years. However, the discovery of gold in California in 1848 guaranteed clippers a prominent place in the American shipping industry. Fueled by the influx of gold miners, the booming economy of West Coast promised huge profits to companies that could supply food and supplies to that area in a timely manner. In 1851, Captain Josiah Cressy of the clipper Flying Cloud set an all-time record of only 89 days from New York, around Cape Horn and into San Francisco, which inspired and challenged other captains taking that route.

A captain might earn $3,000 for a successful voyage, but if he could complete it in less than 100 days, he would be entitled to as much as $5,000. Captain Patten’s fastest time around the Horn was 100 days and 23 hours. It was a respectable passage, but he hoped to shorten it considerably. This would require expert navigation, favorable winds and a devoted crew.

It is understandable then that Joshua was incensed when he caught his first mate, Mr. Keeler sleeping on his watch several times and slowing the ship down by leaving the sails reefed. Patten ordered the man confined below deck. The action reinforced the captain’s authority over Neptune’s crew; but it created another problem. The second mate did not possess the navigational skills to perform the duties of the first mate. Therefore, as the ship’s only remaining professional navigator, Captain Patten assumed Mr. Keeler’s work in addition to his own.

Joshua’s Health Fails

To ensure that the ship remained on course, Captain Patten did not leave the ship’s deck for eight days and nights. Exhausted from lack of sleep, he began to feel ill but continued to perform his duties. As the ship began to approach the most dangerous part of its 15,000-mile journey, the captain collapsed on deck. His condition had not been up to par before this insult to his health, and he was soon very ill with fever, what they called at the time brain fever.

Crewmen found him and carried him below to his bunk. As they struggled to lay him down he struggled violently, out of his head with fever. As the ship rolled heavily from side to side, Mary had the men tie her husband to his bed to keep him from being thrown about the cabin. His condition worsened, and he suffered periods of blindness and deafness. Mary sponged his forehead with cool water and endured his ravings. While he was sleeping, she searched through the ship’s medical books, attempting to find a cause and treatment for his symptoms.

From his prison below deck, the bitter first mate also realized that the ship required a skilled navigator if it were to survive. The New York Daily Tribune would later report:

About one week after the Captain fell sick, the mate wrote a letter to Mrs. Patten, reminding her of the dangers of the coast and the great responsibility she had assumed, and offering to take charge of the ship. She replied that, in the judgment of her husband, he was unfit to be first mate, and therefore could not be considered qualified to fill the post of commander.

Mutiny on Neptune’s Car

The first mate was enraged; when crewmen brought him food and water, Mr. Keeler tried to convince them to join him in a mutiny against Mary Patten. She heard the terrifyng rumors of the first mate’s plot, and she feared desperation might place the crew at his mercy. She could not let that happen. The New York Times later published this report:

Mrs. Patten assembled the sailors upon the quarter-deck and explained to them the helpless condition of her husband, at the same time appealing to them to stand by her and the second mate. To this appeal each man responded by a promise to obey her in every command. … Mrs. P., without a rival, directed every movement on board.

Captain Mary Patten

Mary Ann Brown Patten took command of Neptune’s Car. Nineteen years old and pregnant, she became the first woman in United States history to command a commercial merchant vessel. Her untested skills might not be enough to right the ship, but she refused to sacrifice the $300,000 cargo entrusted to them. With the first mate still confined below and Joshua in a feverish haze, responsibility for the ship fell on Mary. For 50 days she commanded the ship and wore the same clothes.

Cape Horn

The Foster and Nickerson Company had deliberately scheduled a July departure from New York that would allow Neptune’s Car to pass around Cape Horn just as spring arrived in the Southern Hemisphere. But winter conditions still prevailed over the region. As the clipper approached the southern tip of South America, fifty-foot waves and 100-mile-per-hour winds began slamming against the ship. Mother Nature seemed determined to batter the clipper against the 600-foot-high cliffs of Cape Horn’s jagged coastline.

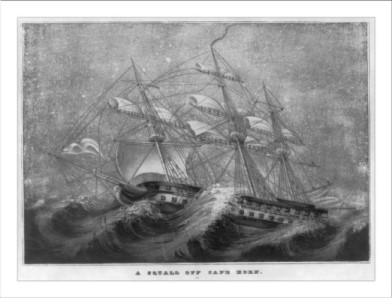

Image: A Squall off Cape Horn

By Currier and Ives

The sky darkened into a swirling mass of clouds, wind and rain. Not sure of their exact location, Mary Patten decided their only chance for survival was to temporarily abandon the westward course. Hoping for more favorable conditions elsewhere, she ordered the ship to sail south-southeast instead. Running with the wind instead of against it, the Neptune quickly escaped the dangers of Cape Horn.

When Mary was not on deck, she was below nursing her husband. His high fever was her primary concern. She shaved his head in an effort to bring his body temperature down, but nothing helped. His only hope for recovery was treatment by a trained physician.

The day after Neptune’s Car began its escape from the violence of Cape Horn, the seas became calmer and sunlight broke through the clouds. Finally able to use the sextant, Mary determined that the ship was 250 miles southeast of Cape Horn. She ordered Neptune westward again, and the men climbed the rigging to set the sails.

Soon after, however, a 15-year-old lookout in the crow’s nest noticed an odd haze surrounding the clouds off the ship’s port side. Crewmen who had survived previous voyages around the Horn knew that meant icebergs. The men scrambled back up the rigging to take in the sails and slow Neptune’s progress, knowing that one wrong move and Neptune’s Car would be lost. For four days and nights, Mary Patten and her crew carefully maneuvered their vessel through narrow channels between the islands of ice. Eighteen days after Mary asked the crewmen to give her command of their ship, she safely completed its westward passage around Cape Horn.

The foul weather was behind them now. The ship made good time northbound off the South American coast. The journey continued without further incident until San Francisco was only a few days away, when the wind stopped blowing. For ten hot days, the ship barely moved. Mary could only sit on the motionless ship and pray for wind.

San Francisco at Last

When the vessel finally arrived in San Francisco, Mary was at the helm and navigated the ship into the port on November 15, 1856. She noted in her log that the trip from New York to San Francisco had taken 136 days – four and a half months. The vessel’s second mate shouted a demand for help in lifting Captain Patten onto a stretcher. The proud captain appeared thin and frail, and his face was ghostly gray. Dockworkers were even more curious by the appearance of a forlorn young woman amongst the all-male crew. From the roundness of her midsection, she was about six months pregnant, but she stayed near Patten’s litter as he was carried to a hospital.

Instant Celebrity

During the next few days, unbelievable rumors spread throughout San Francisco that Captain Joshua Patten’s teenage wife had navigated the great Neptune’s Car around Cape Horn and across 5,000 miles of open ocean. Newspapers around the world began to confirm those rumors. Eager reporters as far away as London began piecing together the sad but inspiring tale. The New York Daily Times gave Mary credit for keeping her husband alive during the voyage. Of the three vessels that left New York at the same time as Neptune’s Car, Mary had beaten all but one of them to San Francisco.

When the word spread of how she had nursed her husband, navigated the ship and protected the vessel’s cargo, all at the age of 19, she was an instant celebrity. The New York companies that had insured the ship and its cargo sent Mary a reward check for $1,000 and a note of thanks. Newspaper reporters who had followed the story were not impressed with the “generosity.” The New York Daily Times, April 1,1857, sarcastically proclaimed: “One thousand dollars to a heroine… from the charitable and grateful hands of eight insurance companies with capitals large enough to insure a navy… .”

Image: Clipper Ship Southern Cross Leaving Boston Harbor

By Fitz Henry Lane

A clipper was a very fast sailing ship used primarily in the middle third of the 19th century. They were yacht-like vessels with three masts and a square rig. They were generally narrow for their length and had a large total sail area. Clippers sailed all over the world, primarily on the trade routes between the United Kingdom and its colonies in the east, in trans-Atlantic trade, and the New York-to-San Francisco route round Cape Horn during the California Gold Rush.

Neptune’s Car‘s owners hired another captain to sail the ship back to New York. As Joshua struggled for his life in a local hospital, the Pattens were left to find their own way back to the East Coast.

In January 1857, the Pattens finally began the arduous two-month return to Boston by way of Panama. Joshua was a Mason, and he thankfully received assistance from the California Masonic Temple, which sent someone to accompany him back to New York and then on to Boston. His condition worsened significantly on the steamships and railroads that transported him home. Their baby, Joshua Adams Patten Jr. was born on March 10, 1857, two-and-a-half weeks after Mary and Joshua had arrived in Boston.

Captain Joshua Patten would never recover. The disease rendered him blind, deaf and incoherent; he never knew that Mary had given birth to a son. He died of tuberculosis on July 25, 1857 at the age of 30. The city of Boston observed a period of mourning by flying harbor flags at half-mast and ringing church bells. The Boston Courier newspaper set up a fund, giving her $1399 to help defray the costs of caring for her husband.

For the next four years, Mary lived in Boston’s North End with her mother and son. On March 15, 1861, Mary Ann Brown Patten also died of tuberculosis at the age of 24.

Young men and women training at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in King’s Point, New York are reminded of Mary Patten’s courage at sea when they pass Patten Hospital, named in honor of America’s first female merchant vessel commander.

SOURCES

Wikipedia: Mary Ann Brown Patten

The Troubled Voyage of Neptune’s Car – PDF

New England Historical Society: Mary Patten Takes Command of a Clipper Ship in 1856

I found Mary and Joshua’s graves inWoodlawn cemetery.

Put flags and flowers to honor them.

What a Great Woman.

Rest In Peace .