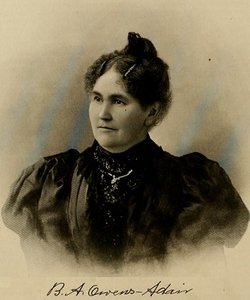

Pioneer, Educator and Founder of Early Oregon Schools

Tabitha Moffatt Brown was an early pioneer on a treachorus journey by wagon train along the Oregon Trail in 1846. She settled with her family in Oregon Country, where she and two reverends founded Tualatin Academy in 1849, and eventually Pacific University in Forest Grove in 1854. In the Oregon State Capitol, 158 names are inscribed in the legislative chambers; only six are women. One of those is Tabitha Moffat Brown.

Early Years

Tabitha Moffatt was born May 1, 1780 in Brimfield, Massachusetts, the daughter of Dr. Joseph Moffatt and Lois Haynes Moffatt. Nothing is known of her childhood. Tabitha married Reverend Clark Brown December 1, 1799, and they had four children – three sons and a daughter: Orus, Manthano, John Mattocks and Pherne (pronounced Ferny). John Mattocks died as a youngster, but the other children survived to adulthood. Reverend Brown died in 1817 and Tabitha taught school to support her family.

Clark Brown’s brother, ship’s captain John Brown, visited the family often over the years and captivated her sons with stories of life on the high seas. Because her sons wanted to be closer to their uncle, Tabitha moved her family to Missouri in 1824. She taught school there as well.

Early Pioneers on the Oregon Trail

Tabitha’s son Orus Brown traveled to Oregon Country in 1843 and became part of a settlement near the present town of Forest Grove. He was pleased with the prospects there and returned to Missouri two years later to persuade his family, his sister’s family, and his mother and uncle to go West with him. By this time, Tabitha Brown was 63 years old and Captain John Brown was 77.

On Wednesday, April 15, 1846, three generations of Tabitha Brown’s family began the long and tedious journey in five wagons. Tabitha’s daughter Pherne had married Virgil Pringle in 1827, and they were accompanied by their six children, ages 7 to 18: Virgilia, Albro, Sarelia, Ella, Emma, and Octavius. Virgil kept a diary and Pherne drew scenes of their trip.

Tabitha and Captain Brown traveled with the Pringles, and they followed the Oregon Trail as far as Fort Hall, in what is now Idaho. Orus Brown acted as pilot for two wagon companies as they came across the Great Plains; therefore, he was usually several days ahead of Tabitha and the Pringles. Orus led his wagon trains on the traditional Oregon Trail across Idaho and into northern Oregon.

Applegate Trail

While they were at Fort Hall in August 1846, still three hundred miles from their destination, Tabitha and her group heard about a short-cut called the Applegate Trail. Mr. Applegate, who had supposedly discovered the new cut-off himself, promised the Browns and the Pringles that he would personally lead them via his new route, and they would reach their destination before those who took the Oregon Trail. The idea of shortening the journey was very appealing to these trail-weary travelers.

Applegate convinced three out of the four trains to take his short-cut, and they paid Applegate to be their guide through the new trail. He had promised to clear the road ahead of the train to allow their wagons to pass easily. However, once the wagon train was on its way, Applegate could not be found. He had disappeared and left them on their own. As they would later discover, his trail did not shorten their journey. Instead it dipped south into Utah Territory and California before finally turning north toward Oregon.

At the aptly-named Cow Creek Canyon, Tabitha’s family lost nearly all of their cattle. The creek was swollen to the brim with icy water from the snow-capped peaks above, and many of the travelers had to wade through water up to their shoulders. Pherne Pringle carried her most precious possessions on her head as she waded across the creek. Tabitha lost her wagon and many supplies, leaving her with a horse and some clothing.

This is an excerpt from a letter written by Tabitha Brown in August 1854, quoted in The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, June 1904:

We were carried hundreds of miles south of Oregon into Utah Territory and California; fell in with the Clamotte and Rogue River Indians, lost nearly all our cattle, passed the Umpqua Mountains, 12 miles through. I rode through in three days at the risk of my life, on horseback, having lost my wagon and all that I had but the horse I was on. Our families were the first that started through the canyon, so that we got through the mud and rocks much better than those that followed.

Out of hundreds of wagons, only one came through without breaking. The canyon was strewn with dead cattle, broken wagons, beds, clothing, and everything but provisions, of which latter we were nearly all destitute. Some people were in the canyon two or three weeks before they could get through. Some died without any warning, from fatigue and starvation. Others ate the flesh of cattle that were lying dead by the wayside.

After struggling through mud and water up to our horses’ sides much of the way in crossing this twelve-mile mountain, we opened into the beautiful Umpqua Valley, inhabited only by Indians and wild beasts. We had still another mountain to cross, the Calipoose, besides many miles to travel through mud, snow, hail, and rain.

The death of children on these overland trails was particularly poignant, but almost impossible to prevent. Virgil Pringle wrote of one such incident:

Made an early start from the springs intending to go to the Port Neuf, but was stopped by an awful calamity in 3Vi miles. Mr. Collins’ son George, about 6 years old, fell from the wagon, and the wheels ran over his head killing him instantly, the remainder of the day occupied in burying him.

Because the so-called short-cut had taken so long, wintry weather set in and travel became very difficult, but they pressed on. After several weeks of constant struggle, the little party reached their limit. Their provisions were running low, their oxen were weak, and the travelers were demoralized.

They sent Virgil Pringle on horseback, hoping he could reach the settlements and bring back food and supplies. Tabitha and Captain Brown also started on ahead; both were suffering from exhaustion. The Pringles eventually caught up with Tabitha Brown and Captain Brown. As snow began to fall, they began a difficult mountain crossing, managing only a mile or two each day.

While the members of the wagon train were waiting for Pringle to return, his eldest son Clark shot one of his father’s best working oxen and dressed it. It was a muscular animal without much fat, but it provided enough food to keep starvation at bay.

Tabitha’s son Orus Brown had taken the Oregon Trail and arrived at Oregon City in September. When news of the suffering of his extended family to the south, he proceeded to gather provisions and pack horses and hit the trail again. As Orus was traveling south, he met Virgil Pringle; who quickly turned around and led Orus back to the family. Orus and Virgil were greeted with joy when they arrived at the little camp of their loved ones.

Encouraged by Orus, Tabitha and her small family finally reached the settlements on Christmas day 1846. Of this group of 22 relatives, aged 2 to 77, not one died on the trip.

Virgil and Pherne Pringle settled just south of Salem, on the creek that bears their name, and the family prospered. One of their sons, Clark Pringle, joined the volunteers to put down the Indian uprising, resulting in the massacre at the Whitman Mission, and afterward married Catherine Sager, one of the girls rescued there.

Life in Oregon

One day, Tabitha Brown noticed something in the finger of her glove, supposing it was a button, but she discovered a picayune, worth about six and one quarter cents. With this small sum Tabitha purchased three needles. She then traded some clothing to Indian women for buckskins, and proceeded to make and sell gloves for the men and women of Oregon. Her first business enterprise cleared around thirty dollars.

Brown’s depiction of Forest Grove, where she eventually settled:

Now I must give you a short description of the beautiful scenery of this delightful and healthful country. The whole of Oregon is delightful, especially the plains, of which there are many, but this West Tualatin is the most beautiful of all others. The outskirts of the plain are circled around with hills, a few miles distant, covering their summits with fine bunch grass, fir and oak timber. Near to the edge, the plain is circled clear around with beautiful fir trees, green all the year, standing three hundred feet high. In front of them, in contrast with the green, there are large spreading oaks casting their shade over the farmers’ white houses, as there are many in full view. Grass is green here all winter, and cattle get their living without being fed. Snow seldom lies on the ground longer than a few days…

In October 1847, about a year after arriving, Mrs. Brown visited her son in the West Tualatin, later Forest Grove. She met missionaries Reverend Harvey Clark and his wife Emeline. The plight of the local orphans had touched Brown’s heart – especially children who had lost both parents on the trip West. She shared her dream of providing a home for them with the Clarks.

The Clarks donated a piece of land, upon which they established an orphanage. With the help of her neighbors and Reverend George Atkinson, Brown gathered supplies and began to provide these children with love and direction. During the first year, Brown also had thirty wards, left with her while their parents traveled south to participate in the California Gold Rush.

Image: Tualatin Academy

Forest Grove, Oregon

Tualatin Academy

This initial institution, the Orphan Asylum, grew to include an Indian training school and eventually evolved into the Tualatin Academy, a secondary school to educate local children. They received permission to hold classes in a local meetinghouse in Forest Grove, Oregon. By 1848, Brown was housemother to the students and a driving force behind the school. The Academy received its charter from the territorial government of Oregon on September 26, 1849 – the first such charter granted.

Pacific University

Since the Tualatin Academy was devoted to educate younger children, the leaders proposed a collegiate department to train teachers. On January 10, 1854 the original charter was changed to create Tualatin Academy and Pacific University. The Academy – with its own principal, faculty and students – operated as a sister institution to Pacific University. Pacific awarded its first baccalaureate degree in 1863, also the first in the region. Congregational missionaries were key leaders in the establishment and growth of the University.

Excerpt from the Statesman-Journal of Salem, Oregon:

Due to the guidance of Grandma Brown, which is what her students called her, the academy and the university thrived side by side. But they weren’t financially blessed. In 1854, Grandma Brown thought about going back East to see if “the rich nabobs and charitable Christian people in the cities” could be talked into making contributions to the struggling Oregon schools. But she ultimately decided that such a trip would be too much for a 74-year old woman to tackle. When she retired she told her brother: “I have labored hard for myself and the public and the rising generation. I now have quit hard work and live at my ease.

Tabitha Moffatt Brown died May 4, 1858, while living with her daughter in Salem, Oregon. She is buried in the Pioneer Cemetery there.

A World War II Liberty Ship built in 1942 was named in her honor. In 1987 the state legislature voted Brown Mother of Oregon, stating that she “represents the distinctive pioneer heritage and the charitable and compassionate nature of Oregon’s people.”

Image: Pacific University

Forest Grove, Oregon

Brown’s great-granddaughter, Mary Strong Kinney, served as an Oregon State Senator in the 1923 and 1925 legislative sessions. According to Oregon Voter magazine, “her business experience was so broad that she had a ready comprehension of legislative problems” and she “bore herself with distinction and dignity.”

SOURCES

The Story of Tabitha Brown

Wikipedia: Tualatin Academy

OCTA: Clark and Tabitha Brown

Oregon Encyclopedia: Tabitha Moffatt Brown

Tabitha Moffat Brown is my 5th great-grandmother. It has been wonderful to find so much material about her. Orus is my 4th great-grandfather.